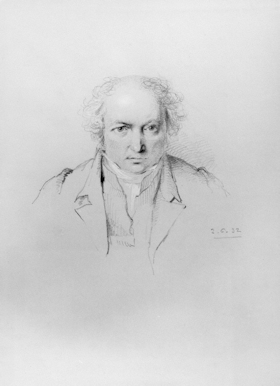

John Thomas Smith - William Brockedon, Chalk 1832 (National Portrait Gallery, London, UK)

John Thomas Smith - William Brockedon, Chalk 1832 (National Portrait Gallery, London, UK)

John Thomas Smith, born in a Hackney carriage in London (23 June 1766), was a painter, assistant sculptor, draughtsman, engraver, antiquarian, and curator. As an antiquarian, his primary interest, Smith had several notable publications; among them, "Antiquities of London and its Environs" (1791, "Remarks on Rural Society" (1797), and "Antiquities of Westminster" (1807). Given these antiquarian interests, he held the nickname of "Antiquity Smith." As a curator, Smith held the position of Keeper of Prints at the British Museum for 17 years (from September 1816 until his death in 1833).

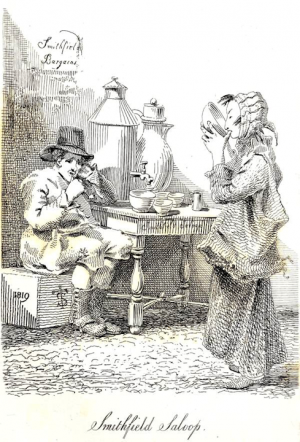

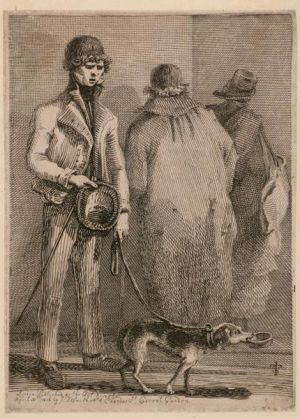

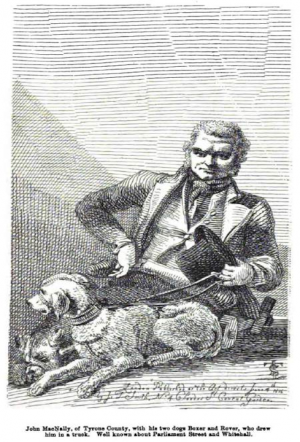

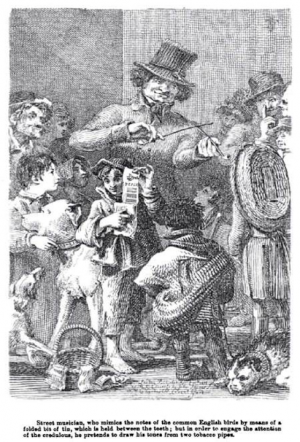

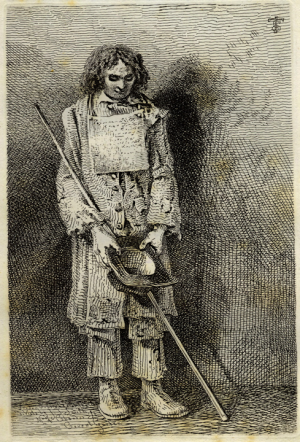

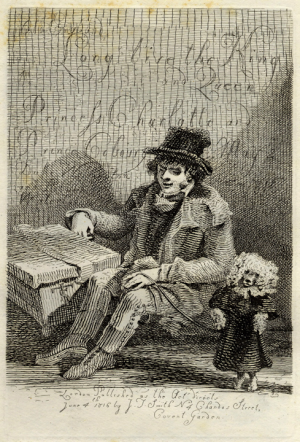

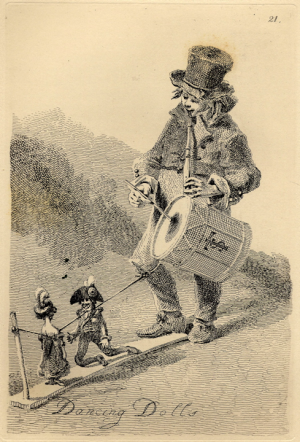

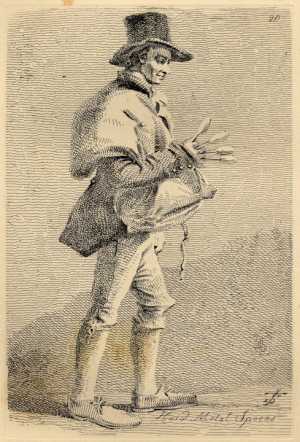

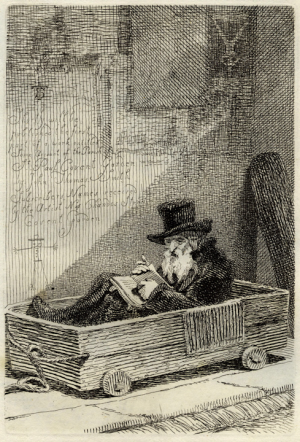

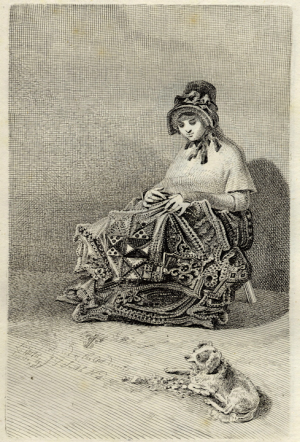

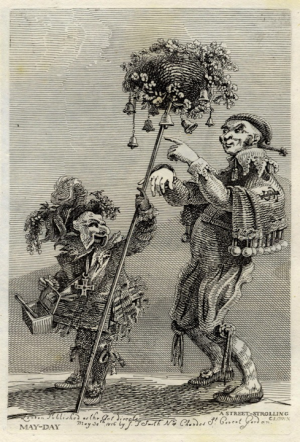

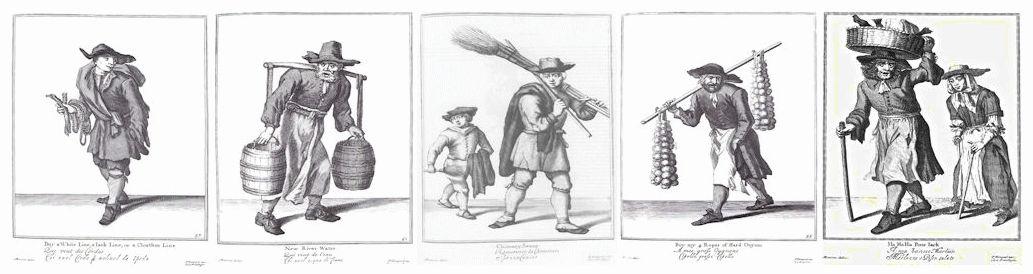

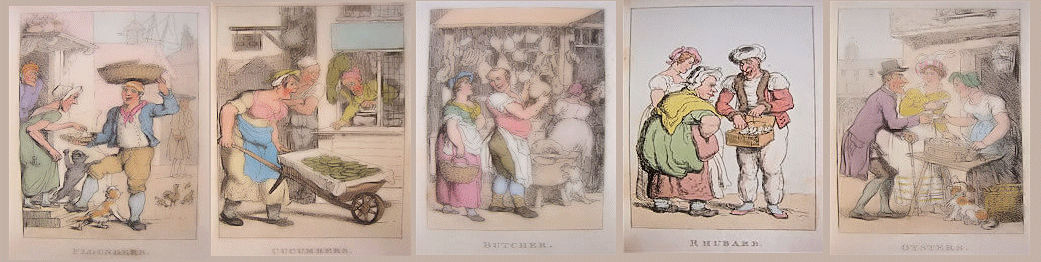

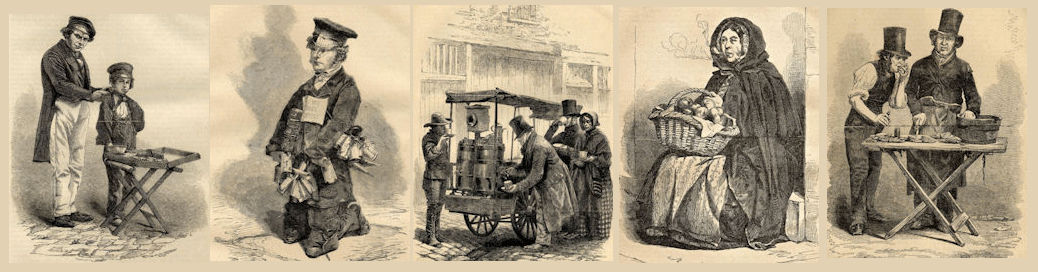

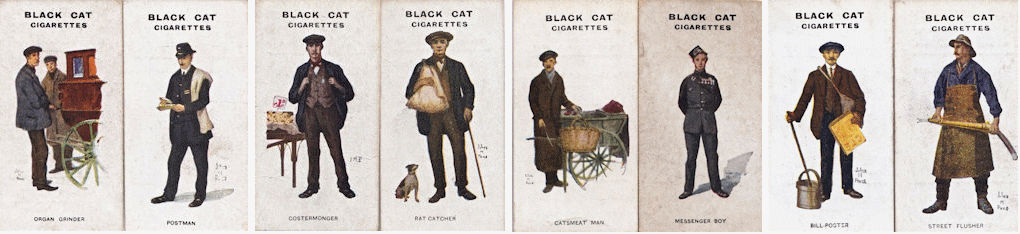

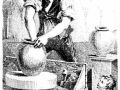

A friend of Thomas Rowlandson, Smith also drew and engraved the "curious characters" that he encountered in the streets of London. During his rambles through the London streets, Smith drew and interviewed numerous vendors or hawkers of goods and services (street criers). He also, quite interestingly drew and interviewed numerous beggars (mendicants, vagabonds). Of the two, Smith is probably more known for his focus on London beggars.

In 1817 Sherwin and Freutel published a book of Smith's etchings entitled "Vagabondiana, Or Anecdotes of Mendicant Wanderers through the Streets of London with Portraits of the Most Remarkable Drawn From Life." Several of the images presented in the following gallery originate with this source.

After Smith's death in 1833, three additional postumous publications should be noted. In particular, John Bowyer Nichols published, in 1839, "The Cries of London, Exhibiting Several of the Itinerant Traders of Antient and Modern Times." According to Nichols, this volume was prepared by Smith before his death and should be considered a continuation (or second volme) of "Vagabondiana." Several images from this source, especially from the "modern Trades" section, appear in the gallery below.

In 1845, Richard Bentley (London) published Smith's "A Book For a Rainy Day: Or, Recollections of the Events of the Last Sixty-Six Years." And in 1846, Bentley published Smith's "An Antiquarian Ramble in the Streets of London, With Anecdotes of Their More Celebrated Residents" (in two volumes, Charles Mackay, ed.).

For the curious reader, there are, as one might expect, a number of editions to these original four publications that are currently available in both physical and electronic forms. Google Play Books, Amazon, and the Guttenberg Project would be helpful starting points. Additional reference links, about Smith and his work, may be found HERE.

On a more personal note, I must admit to a great respect and fondness for the humanizing and educational natures contained in the London street artistry of John Thomas Smith. In the "Preface" to "Vagabondiana," Smith quotes Granger (Biographical History of England, from Egbert the Great to the Revolution, consisting of Characters dispersed in different Classes, and adapted to a Methodical Catalogue of Engraved British Heads. Intended as an Essay towards reducing our Biography to System, and a help to the knowledge of Portraits; with a variety of Anecdotes and Memoirs of a great number of persons not to be found in any other Biographical Work. With a preface, showing the utility of a collection of Engraved Portraits to supply the defect, and answer the various purposes of Medals, 2 vols. Lond. 1769, and a supplement consisting of corrections and large additions, 1774) as noting that " . . . Lord Bacon has somewhere remarked, that biography has been confined within too narrow limits; as if the lives of great personages only deserved the notice of the inquisitive part of mankind. I have, perhaps, in the foregoing strictures extended the sphere of it too far. I began with Monarchs, and have ended with Ballad-Singers, Chimney-Sweepers, and Beggars. But they that fill the highest and the lowest classes of human life, seem, in many respects, to be more nearly allied than even themselves imagine. A skilful anatomist would find little or no difference, in dissecting the body of a king and that of the meanest of his subjects; and a judicious philosopher would discover a surprising conformity, in discussing the nature und qualities of their minds."

Smith rambled the streets of London and took it upon himself to draw and etch the likeness of many to cross his path(s). He also, to his great credit, endeavored to "draw" some of the biography, habit, and history of street individuals and trades (beggary included). In this regard, Smith allows the reader to not only "see," but also to understand (cue Bacon here on both knowledge and charity) these subjects as human beings; human beings not unlike ourselves, but too often considered inferior, treated as pests, or simply overlooked.