Why Do So Many Kids Read V.C. Andrews?

My favorite song has lyrics that go something like this: I hid it in between pages of a textbook during class. My friend found it in her mom’s nightstand drawer. I got it from a friend. An older sister. And once I started reading it I couldn’t look away.

So what’s this song about?

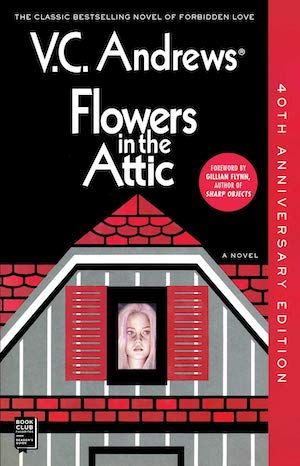

The ghostly face can’t be denied.

The ghostly face can’t be denied.A book by V.C. Andrews, frequently Flowers in the Attic. That novel follows siblings Cathy and Chris Dollanganger, trapped in an attic by their flighty mother and cruel grandmother and left to fend for themselves, with dire consequences. I loved this piece in The Toast chronicling some readers’ first encounters with the scandalous text. Other books by Andrews take on similarly twisted topics. My Sweet Audrina, for example, chronicles the life of an isolated girl named Audrina. She has an unreliable memory but wishes to be as loved as the first Audrina, her murdered older sister. These short descriptions barely scratch the surface of the grotesque gothic drama within, honestly.

It’s amazing that these 40-year-old books can still hold young readers in their thrall. I’ve written before about what I personally love about the subversive trash that is Flowers in the Attic, but there has to be a broader pattern, right? So I’ve come up with a few theories about why V.C. Andrews is such an enduring author. Let’s have a look.

They’re About Young People But Not FOR Young People

V.C. Andrews’s books are not YA fiction. Her publisher, Simon & Schuster, currently categorizes them as fiction, as opposed to teen fiction, on their website. They were not originally marketed as books for teens or tweens either, yet here we are. They are instead many a reader’s foray into adult fiction, along with Stephen King.

Stephen King and V.C. Andrews share much in common, in fact. One could even imagine in a different world, Andrews would get similar treatment, with star-studded adaptations on the big screen instead of the Lifetime network, or serious reviews in distinguished outlets. After all, they share a lot of sensibilities. They aren’t afraid to root around in salacious and shocking subject matter. They are both interested in the loss of childhood innocence. And they often center stories around young people, making them obvious picks for curious young readers.

Part of the reason culture doesn’t hold Andrews at the same level as King is good old-fashioned sexism. But also, Virginia C. Andrews’s career was cut short by her death in 1986. Andrew Neiderman continues to pen books under the V.C. Andrews name. For the purists, the books written by Virginia herself are the gold standard. This includes the first four books of the Dollanganger series, with Flowers in the Attic leading off. My Sweet Audrina is Andrews’s only standalone novel. Finally, Andrews completed the first two books in the Casteel series, Heaven and Dark Angel.

While Andrews’s series may follow characters into adulthood, all of these begin with the main characters as children and adolescents. A common rule of thumb for many people suggesting books for kids is to recommend books with protagonists their age or a little older. Even if an adult isn’t handing a V.C. Andrews book to a child, a young reader picking it up will meet characters like others they’re encountering in their regularly scheduled reading.

They’re Abundant

Many readers primarily associate V.C. Andrews with incest (in Flowers in the Attic it’s not consensual). I’ve found other books, published more recently than the 1970s-80s, that veer into that taboo territory. One might assume these other titles could supplant Andrews’s work. Things get stale with time, right? But few are quite as daring as a typical Andrews novel. How We Fall by Kate Brauning includes a relationship between first cousins. Did I Mention I Love You? by Estelle Maskame takes it to step-siblings. Tabitha Suzuma’s Forbidden is even more popular, based on total Goodreads reviews, depicting a sibling relationship. It is even marketed as a Flowers in the Attic read-alike, with two older siblings who care for their younger siblings because of a neglectful mother.

None of these books, however, have the sheer omnipresence of V.C. Andrews’s books. Her books were runaway bestsellers from the start. According to the Guardian, 40 million copies of Flowers in the Attic have sold worldwide. She’s truly in another league. These numbers make it so easy to stumble across copies of her books. At my local used book fair, I frequently find entire boxes full of Andrews titles. Unsurprisingly, the same is true of Stephen King. Even if a school library doesn’t shelve Andrews — the books are considered adult fiction! — public libraries might have dozens of titles. Check any thrift store, garage sale, or Little Free Library. V.C. Andrews is practically in the water.

From my own experience as a lifelong enthusiastic used book scrounger, only the Twilight Saga and Fifty Shades series are anywhere near the level of saturation of King and Andrews. And all it takes to pull a reader into a V.C. Andrews book is an iconic shiny foil cover featuring haunted faces surrounded by Gothic details. The best editions feature the keyhole cutouts revealing a whole freaky tableau under the cover.

They’re Forbidden Fruit

A book with an official seal on the cover could never.

A book with an official seal on the cover could never.Another part of the appeal is the forbidden nature. Some parents and teachers outright ban the reading of V.C. Andrews, naturally making it all the more appealing. Kids know what’s up. Sneaking the book past watchful eyes is part of the pleasure.

By contrast, take a book like Meg Rosoff’s How I Live Now, a dystopian novel about teens surviving a third world war in England. It boasts a taboo element, with a relationship between cousins. But it also has a Printz award sticker right on the front. No book that garners such official praise is likely to be the one that gets passed between friends and read on the sly.

On top of that, as the editor of Flowers in the Attic pointed out in an interview, publishers aren’t willing to take a chance on books as risky (and risqué) as V.C. Andrews’s nowadays.

They’re a Perfect Storm of Taboo, Fear, and Rage

While other authors may take on salacious and taboo topics, few pile so many into a horrifying parfait like V.C. Andrews can, and that’s what makes her work singular. She will take all the dark topics — the abuse, the rape, the murder via poisoned doughnut — and use them to confirm every fear you might have. That your parents are monsters. That you might turn into them one day. Thus, every angry feeling you have toward them is justified. You might be able to exorcise these feelings through reading, or you might have a schadenfreude reaction, thankful these Dollanganger and Casteel kids have it worse.

Ultimately, I take so much joy knowing these books still find the readers who need them for whatever reason. Some kids are attracted to dark topics, and reading about them is a relatively safe way to explore that curiosity. Plus, some of those kids grow up to be fantastic writers themselves, like Megan Abbot and Gillian Flynn, who’ve written about their own experience with V.C. Andrews. To do my part, I’ll toss a V.C. Andrews into the Little Free Library on my block every now and then. If a paperback ever goes missing while kids are visiting my house, I’ll stay mum. And I’ll smile a knowing smile if, decades later, they ask the question “Who let me read this stuff?” while reflecting on their youthful reading habits.

Copyright

© Book Riot