We Need the Eggs: On Annie Hall, Love, and Delusion

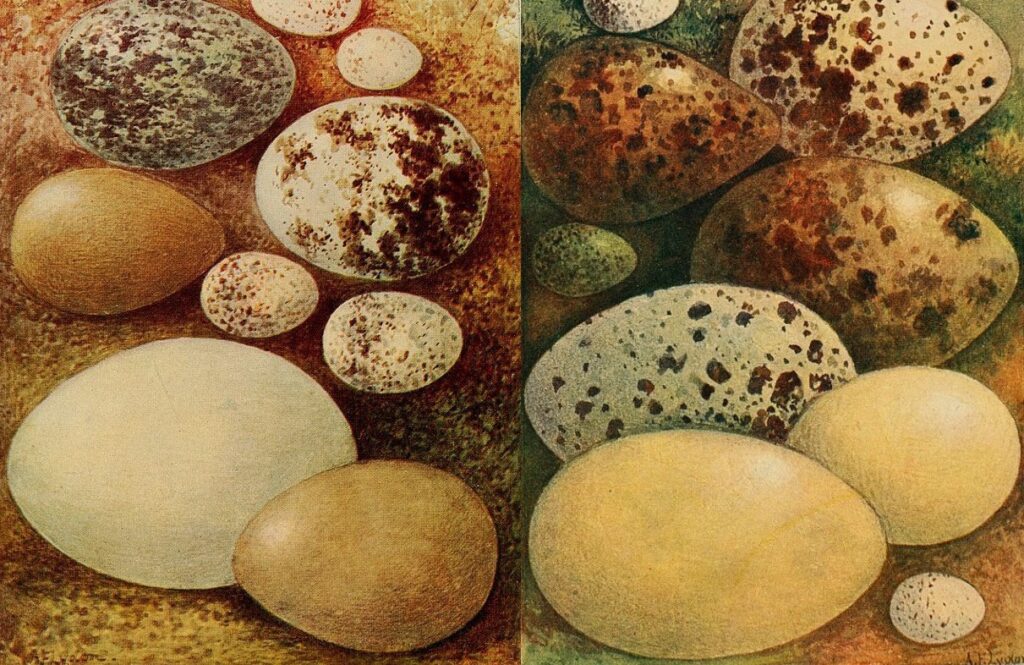

TWO ILLUSTRATIONS BY RICHARD KEARTON, 1896.

One night, my stand-up comic brother, David, and I were sitting on my couch, talking about the joke that concludes Woody Allen’s 1977 film, Annie Hall. We’d watched the movie together dozens of times growing up, and we’d always assumed that we interpreted the ending—about how people get into relationships because we “need the eggs”—the same way. That night, we discovered we did not, and even after much talking, we found we couldn’t agree on the joke’s meaning. In the weeks that followed, I longed to restage and expand our conversation, and hopefully to answer some of the questions it had raised, so I invited a few other people into the discussion: Zohar Atkins, a rabbi and poet; Nathan Goldman, a literary critic and editor; and Noreen Khawaja, a professor of religion who has written a book on existentialism. Could we, together, get to the bottom of this profound and amazing joke?

DAVID HETI

The joke came up one night when Sheila and I were talking.

SHEILA HETI

I think we’d been talking about relationships.

DAVID HETI

And I said how I understood the joke and then Sheila had a completely different interpretation. We couldn’t settle on what it meant.

SHEILA HETI

Let me read the joke. It’s at the very end of the movie, and Alvy is talking about meeting Annie for coffee, and he says, “After that it got pretty late and we both had to go, but it was great seeing Annie again. I realized what a terrific person she was and how much fun it was just knowing her, and I thought of that old joke—you know, this guy goes to a psychiatrist and says, ‘Doc, my brother’s crazy! He thinks he’s a chicken!’ And the doctor says, ‘Well, why don’t you turn him in?’ And the guy says, ‘I would, but—I need the eggs.’ Well, I guess that’s pretty much now how I feel about relationships. You know, they’re totally irrational and crazy and absurd, and I guess we keep going through it because most of us … need the eggs.” The funny thing about the joke for me is that there are no eggs. Just because the brother thinks he’s a chicken doesn’t mean there are eggs. And David was like—

DAVID HETI

It’s not about there being actual eggs! Lovers go into a relationship because they each get something out of it, and whether there’s something objectively there doesn’t matter. Each party gets the messiness and the intimacy and whatever you get—that feeling of something being there. Alvy Singer has all these divorces, but he’s saying that we keep doing it, ultimately, because we’re crazy: one of us thinks he’s a chicken, and the other one’s on the psychiatrist’s couch, thinking he’s getting eggs.

GOLDMAN

That’s interesting, because I’ve been wondering why there are two deluded people in the joke, and it seems like you’re suggesting that it’s because it’s about a kind of delusion that requires multiple participants—even though in the joke, the speaker at first frames it as only his brother’s delusion, before he reveals he’s participating in it.

SHEILA HETI

I think it’s true that a romantic relationship is a sort of delusion between two people. There’s an agreement to imagine something together, and you create this idea of each other and the relationship and what you mean to each other. And when one person stops imagining all this, basically that’s when the whole thing falls apart.

KHAWAJA

I saw the two brothers not as two people in a relationship, but as two versions of Woody Allen—or Alvy. One has the perspective of, “It’s crazy, I’m living in a fantasy of this other person and myself,” and the other one is saying, “Yet I’m still getting something out of it, so he’s seeing it from both sides.” And to Sheila’s point, I think he’s saying that there are eggs. The funny thing is, there shouldn’t be eggs, but there are eggs.

DAVID HETI

I think it’s important that the person speaking knows it’s a bit crazy what he’s proposing. He has to have that self-awareness for it to be so funny.

SHEILA HETI

I don’t think he knows he’s crazy. I think “I need the eggs” is the straight-man line. It’s like you originally said, David. He believes there really are eggs.

GOLDMAN

So he’s cognizant that his brother is crazy, but not that he is?

SHEILA HETI

I think so. Which is another reason why this joke is so perfect about relationships, because we always think the other person is crazy but we’re not. All we talk about when we talk about our relationships is how crazy the other person is.

ATKINS

I can’t even track how many layers of meta this joke is, but one that just came to me is the idea that maybe the joke doesn’t actually make sense, but we need it to make sense, because we need the eggs. Why do we laugh at a joke? Is it because the joke is funny, or because we need the release? So we’re almost complicit in the insanity, because he tells a story that doesn’t really hold together, but we need the closure, the laughter, so we’re brought in. Likewise, he’s both the butt of the joke and the one telling it. In the classical form of a parable, there are two parts: there’s the allegory, and then there’s the interpretation, and usually the interpretation is given by somebody else. A classical parable would end with just, “I need the eggs,” and then another person would come and say, “Oh, it’s like relationships.” But here, where does the parable end—when the joke ends, or when he steps out of that role to interpret it? By being the interpreter of his own parable, Woody Allen extends the boundary of the parable to include the interpretation. And in doing that, parable makes the interpreter less superior to the interpreted, because it shows that you can be a very rational, meta, balcony-view kind of person, and be just as crazy as the people you’re looking down on.

DAVID HETI

Why does that make the interpreter inferior? I think that elevates him. First off, this is not Alvy Singer telling the joke—this is Woody Allen, the director, so he is outside it. It’s like the opening joke: “I would never want to belong to any club that would have someone like me for a member.” Here you have one guy who thinks he’s a chicken, which is a problem, and another guy who thinks he’s getting eggs, and that’s a problem, too, but you have these two things together and it turns out it works out beautifully!

SHEILA HETI

I don’t agree with you necessarily that the person who tells the joke is Woody Allen and not Alvy Singer.

GOLDMAN

I agree, I don’t think that’s clear. But I’m also not sure I agree with Sheila that the narrator doesn’t come to understand that he’s crazy. I think this question has stakes because it relates to the question of whether there are delusions you can participate in despite being self-aware—like free will, maybe. Is there a role for self-awareness in delusion? Does humor let us live self-awarely in delusion, or does it only diffuse it?

ATKINS

I’m now thinking of a Hasidic story about a guy, a prince, who thinks he’s a chicken, and he refuses to sit at the table, and he’s going underneath the table and eating the crumbs and making chicken sounds, and the king hires all these wise people to come visit and cure the son of his pathology, and none of them succeed. Then someone goes under the table with the guy and pretends to be a chicken as well. After he imitates him for some time, he’s like, “Wouldn’t it be fun to pretend to be human?” Like Alvy’s joke, it’s about being in on someone’s pathology as a way of healing them.

DAVID HETI

I think one joke that we’re all forgetting about is Alvy’s comment to Annie Hall on the plane that a relationship is “like a shark”—“it has to keep moving or else it dies.” Part of the magic of a relationship is that you can’t hold it down, you can’t put a finger on it or resolve it. It exists in the tension. Same with the joke. We are trying to resolve it, but we can’t.

SHEILA HETI

Right. If the guy accepted that his brother was a chicken, like very calmly—“This is great, he’s a chicken, and I get the eggs”—there wouldn’t be the anxious tension which keeps romantic relationships interesting. In some way, his dissatisfaction with the fact that his brother is a chicken is the eros—it’s the excitement that keeps the shark of the relationship moving. The answer is not, “Be happy that he’s a chicken and don’t see that as crazy.”

KHAWAJA

Nor is it to find the perfect person—

SHEILA HETI

KHAWAJA

And who satisfies all the things you think you want.

SHEILA HETI

Yeah, it wouldn’t be a better brother who didn’t think he was a chicken, but didn’t give eggs.

ATKINS

Exactly! He thinks he wants a life without struggle, and he’s looking for the perfect soul mate to ease all that tension, when in fact it’s the tension itself that’s producing the love interest.

DAVID HETI

And it’s the tension itself that creates … well, life. Because eggs represent fertility, life.

SHEILA HETI

But I think my original question was, Are there eggs, actually, in a relationship? Like, what are we getting? Are we getting eggs, or are we getting the illusion of eggs, or what?

GOLDMAN

At the risk of evading that question, it’s interesting to me that in the joke, it’s the narrator, not the brother, who introduces the eggs. When he says, “My brother thinks he’s a chicken,” that implies eggs, but it’s he, the narrator, who actually brings them up. I think that might help us understand what the joke is saying about relationships. Because we only know for sure that the eggs exist for one person—for the one who’s talking to the doctor.

SHEILA HETI

Right, we don’t know if the eggs exist for the guy who thinks he’s a chicken.

GOLDMAN

He could think he’s a barren chicken.

KHAWAJA

The classic chicken-and-egg joke is also just sitting there! “Which came first?” If the joke is refuting the idea that you can have the eggs without having the chicken, then it actually becomes a summary of that other joke. I think that’s floating somewhere in the funniness. And I feel like the eggs could be … whatever illusion yields. Like, not real eggs or false eggs, but whatever the fruit of illusion is. The one other egg moment in the film is when Alvy’s on the street doing a survey with the passersby, and he asks an Upper West Side older gentleman, How do you and your wife make it work after all these years? And the guy’s like, “We use a large vibrating egg.” The guy gives him a very reasonable answer, but Alvy is like, “Well, you ask a psychopath for advice, that’s what happens.” His reaction to the possibility of a vibrator is to be scandalized! He thinks it’s psychotic because it’s artificial. When I saw that, I thought, it’s not that mysterious why he and Annie failed. He tried to stop her from smoking pot before sex, and that was where everything went completely askew. Alvy is like, I want the eggs that come from when you’re relaxed; I don’t want you to use something artificial to get there. He wants her to get there “naturally.” So there seems to be some kind of echo there—he wants the fruit of the illusion, but he can’t accept the intentionality; that techniques may be needed to produce the illusion.

ATKINS

Right, you can’t pick and choose the things you want in a person. He says, “I don’t like that my brother’s insane, but I do like the eggs,” and the response to that is, “If you want the eggs, then you have to embrace his crazy.” If you want to reject his crazy, fine, but you don’t get his eggs. I suppose that’s a way of saying the eggs are sort of real.

GOLDMAN

And actually, the thing that you think is a problem sometimes produces exactly the thing you want. There’s that recurring thing where Annie is like, “You don’t think I’m smart enough.” And it’s true that Alvy does think that, and it annoys him. But he also enjoys his paternalistic, educating role.

SHEILA HETI

So what are the eggs? Not in the joke—but in relationships.

GOLDMAN

I could answer with respect to what I like in relationships, or what the film says about what’s valuable. But do people participate in relationships for the same reasons, fundamentally? I’m not sure. I think it speaks to that uncertainty that within the context of the joke, the eggs are a cipher, a determinate indeterminacy. An egg is a nascent, generative image of pure emptiness, of negativity, of potentiality. It could be anything.

SHEILA HETI

Yeah. I think that’s why the joke works—because when we hear we “need the eggs,” we all know what that means to us. I know what the eggs I need are. It’s such a nice mood to end the movie on. And the hardest thing to do in a work of art is to conclude it well.

GOLDMAN

One of the things that I think it makes a great conclusion is that, for a movie that’s very ironic and modern, it ends with a moral, in a strangely classical sense—relationships are like this. But all the things we’ve been discussing—the indeterminacy and irresolution and the fact that it’s a joke—undermine that didactic quality. So you get both at once. Here’s what relationships are like, and also a question mark.

SHEILA HETI

Here’s what relationships are like—we don’t know what we’re getting out of them.

KHAWAJA

DAVID HETI

This whole thing reminds me of that scene in the movie where he’s at the party and is watching the Knicks and his wife comes in and Alvy says, “All those PhDs are in there, you know, like, discussing modes of alienation and we’ll be in here quietly humping.” We’re not enjoying the joke! No one’s enjoying the joke here!

SHEILA HETI

And no one’s really answered my question. What are the eggs?

KHAWAJA

I think the eggs for me are the feelings I get from the version of me that my partner creates through their delusion. Whatever that fantasy they have of me, and of themselves in relation to me, yields—that’s the eggs. And maybe I’m suspicious of it, too, because they’re not really right, but it’s still what holds me there.

SHEILA HETI

What holds you there is their image of you?

KHAWAJA

The thing I can sort of see through about the way they see me. With one eye. I’m like, “Oh, I can see that that’s maybe not right.” Maybe there’s some fantasy element in that, but it gives me this hope, right? That fantasy or that generativity, the fact that they’re generating possibilities …

SHEILA HETI

And the way that they see you is usually a picture that’s better than yourself and worse than yourself.

ATKINS

I’m just curious to know—in the brother-brother relationship, who’s doing the work? Who’s being centered? We get the story from the point of view of the one saying, “I need the eggs,” but we don’t get the chicken’s side of the story.

SHEILA HETI

Instinctively, it seems to me like it’s the chicken that’s doing the work, because that’s a lot of work: to be a chicken. And to believe yourself a chicken.

GOLDMAN

And the physical act of producing eggs is also a lot of work.

KHAWAJA

To believe yourself a chicken sufficiently enough to produce some kind of egg that the other person is getting—there’s a lot of work in that belief!

GOLDMAN

But isn’t having a delusion no work at all? I wake up in the morning and effortlessly believe all kinds of things about myself that aren’t actually true. (Pause.) I am trying to think about whether the joke only works if the brother’s not there. Or is there a version of the joke where the brother is there that is funny in a different way, and that tells us something different?

DAVID HETI

Maybe the other brother is on the couch talking to his psychiatrist, saying, “He wants eggs from me!”

SHEILA HETI

And why is it two brothers in the joke? If what we’re meant to do is extrapolate this to a romantic relationship between Alvy Singer and his girlfriends and wives, why isn’t the joke, “My girlfriend thinks she’s crazy?” Why is that not as good of a joke?

GOLDMAN

Because brothers can’t break up with each other.

ATKINS

Alvy can keep breaking up with specific people, but he can’t break up with the concept of a relationship—the brother is the stand-in for that. The family relationship represents the idea of relationship itself, in a way that actually makes the problem of how you choose a partner a specifically modern one. It almost seems easier to be assigned one and be told, “This is your brother, go and figure it out.”

SHEILA HETI

Watching this movie I did kind of feel like, Well, their problems weren’t so bad that they should have broken up. Like, okay, Alvy is a bit of a drag for Annie. She wants to have more fun. But why can’t she have fun apart from him? And they do love each other. So, based on what Zohar is saying, the answer for him is, Don’t break up. You need the eggs. You need the relationship. Not that the moral of the movie is that they shouldn’t have broken up, but that’s … some wisdom.

ATKINS

I feel like he takes it in an opposite direction, though—I’m going to be a serial dater my whole life, because “I need the eggs.”

DAVID HETI

But those aren’t the good eggs. Those aren’t the deep eggs—the real craziness you can get to in a long-term relationship.

ATKINS

So does he misinterpret his own joke? Or is the joke sufficiently indeterminate that it’s more of a Rorschach test for him and for us to figure out how we feel about relationships?

GOLDMAN

I think the joke and the film are agnostic about the question of lifelong monogamy. It’s interesting that the joke follows the scene where they meet and he says “how much fun it was just knowing her.” At that point, he isn’t saying, We were really good together, we should get back together. So the movie kind of brackets the question of the best way to produce the eggs, or to get them.

KHAWAJA

I agree that it’s agnostic on the monogamy question, and I don’t know that you need endurance for eggs. I think the eggs come at all sorts of points.

GOLDMAN

It’s interesting that he says, “That’s pretty much how I feel about relationships” and not “romantic relationships.” I mean, in the context of the film and how we generally use that word, it makes sense to interpret that narrowly—romantic, sexual relationships—but could we also take it as true about relation in general?

SHEILA HETI

No, I think the joke is talking specifically about romantic relationships, because you wouldn’t say that friendships are “totally irrational and crazy and absurd.”

GOLDMAN

Why not?

SHEILA HETI

Because you have a degree of choice over who your friends are, but you don’t choose who you’re sexually attracted to, and you don’t have any agency over who you fall in love with. I think it’s the wild not-making of a choice that makes romantic relationships crazy and absurd. “How did I find myself in relation to this person whom I can’t seem to get away from, but whom I actually don’t want to get away from?” With a friend, it’s a bit more understandable—you have things in common. The reason you spend time together makes more rational sense.

ATKINS

DAVID HETI

There’s a sadness to that, I think. “I need the eggs.” That line could be delivered in many different ways. “Well, I need the eggs.” It’s kind of an admission of his failing. It’s out of his hands.

SHEILA HETI

In friendship, there’s actual eggs. In a friendship, you get real eggs.

(Everyone laughs.)

KHAWAJA

Well, I think it depends on whether there are erotically charged elements to the friendship. Friendship can be magnetic, too.

SHEILA HETI

That’s true. Certain friendships can also feel fated, absurd and irrational. Do you guys think the crazier, more erotic, more combustible relationships have better or bigger or more potent eggs than romantic relationships that are more placid, or do the more placid, amicable relationships have bigger and better eggs? Or is the joke making no comment on the quality of the eggs in relation to the type of relationship?

KHAWAJA

I don’t think the quality of the eggs is dependent on the tempestuousness of the relationship, because if we’re tying the eggs to fantasy, then we have to acknowledge that a placid relationship is full of fantasy, too. You think of the other as stable, as unchanging, and you’re both playing along with that: “We do things this way, and this is what we like, and it’s not going to change.” But you both probably know, somewhere, that it could change. You could have a tempestuous relationship that had terrible eggs, or a very placid relationship which was very fictional, actually, but which gave you tons of good eggs.

ATKINS

I think I agree with Noreen that we get the lovers we deserve. In that relational sense, if you are a placid-seeking person, you get a placid-seeking person in response, and that’s great. But I do think that on a more absolute level, just as there’s excellence in any realm of craft, there probably is excellence in the realm of relationships. Some relationships are brave and others are less so, and I think the braver the relationship, the more conflict will be surfaced, and therefore a deeper harmony will be achieved. Therefore, better eggs.

SHEILA HETI

What constitutes bravery in a relationship for you?

ATKINS

I think a willingness to go to uncomfortable places. I guess I’m a brooding type, and a person who likes to self-examine, so I value that in a partner. But if skiing with your partner is your thing, fine, that’s not worse than talking about your childhood wounds.

SHEILA HETI

I’ve never heard a person so confidently suggest that excellence in a relationship equaled bravery. It’s like you’re saying bravery in a relationship equals beauty in a work of art.

ATKINS

Now that I hear it reflected back, I’m not sure that I would stand by it.

GOLDMAN

I think it’s an interesting claim with respect to the film, because while you could make the argument that Annie Hall is a brave work, or a very self-assertive one, in some ways the defining characteristic of the movie—and the paradigmatically Jewish American, mostly male aesthetic it embodies—is actually a kind of cowardice. Or maybe that’s not right, but a neurotic, self-deprecating—

KHAWAJA

—failure to meet what’s demanded of him. Yeah, he doesn’t manage to get it right.

I guess we were saying two different things about what the eggs come out of. One is conflict—from which you get bravery. The other thing about the eggs is the element of fantasy. Does it constitute bravery to accept that there’s a delusive aspect to our most meaningful relationships? I feel like avoiding conflict would be him saying, “Right, I know the eggs come from the crazy, but I’m not going to try to excavate where my brother’s belief that he’s a chicken is coming from. I’m not going to try to shake him into reason, I’m just going to let him have his thing, because I’m getting these eggs.” That’s not necessarily a working-through of something.

GOLDMAN

Right, the picture you just described feels placid, not generative. And it cuts off the possibility that both participants might have an awareness of the delusion of the enterprise, yet still be interested in investigating it together.

KHAWAJA

I mean, speaking of the difficulty and deludedness of the enterprise, there’s also the “art and the artist” problem. Can you accept or appreciate one and not the other?

GOLDMAN

Right, like, if we need the eggs—the artwork, or whatever—do we have to take the chicken, too?

KHAWAJA

On the one hand it seems like we are saying yes, or that the joke is saying yes. I think what the very idea of art means is that there is a difference between the two. Somewhere. Not a brick wall, but… I think, yes, you’re in a relationship with both the art and the artist, but they don’t have to be the same kind of relationship.

GOLDMAN

So where is that line?

KHAWAJA

I don’t know in the abstract, and even if I did, I doubt the five of us would agree on where it is. I just think that orienting something as a work of art means that a line between chicken and egg exists, or can be drawn.

SHEILA HETI

A line between the chicken and the egg, or between the two relationships, or between the art and the artist?

KHAWAJA

Let’s say I’m glad Woody Allen made Annie Hall, and glad Woody Allen is not my brother.

SHEILA HETI

For the record, my father really wanted to name me Woody Allen. But my mother said she’d run away with the baby. (Laughter.)

GOLDMAN

If this is a joke about the necessary delusions that sustain a relationship, does it also speak to the delusions that sustain life in general? As in, if modernity and postmodernity are epochs in which everything has become disenchanted and historicized and revealed to be socially manufactured—even the very notion of romantic love—we have two options. We can bracket that and live our lives not thinking about it, or we can say, Yes, it’s all constructed, but that doesn’t make it any less real.

ATKINS

If we read this as being about modernity and our relationship to inherited myths—if that’s another possibility for the joke, that we’ve been handed all these traditions, and we kind of need them for the eggs, even though we can no longer believe in them sincerely, like people did two thousand years ago—to what extent are we deluded in thinking that we have a choice, if in fact we are operating from a powerful unconscious drive? If you hear from someone who’s complaining about a relationship they’re in, but they’re not breaking it off, and you’re like, “Get out of there,” and they’re like, “Well, I need the eggs,” I mean, you’d probably be concerned, right?

But you might also say, “You know what? If that’s their choice—clearly it’s doing something for them. I shouldn’t just be listening to what they’re saying consciously. I should be observing their unconscious, and their unconscious is saying, ‘Yeah, I love it.’” Similarly, the rational project is all about debunking religion, or debunking myth, and meanwhile, so much of what we do continues to be mythical or irrational. I think the lesson might be that we can’t reason our way out of delusion. Delusion is so much bigger than what we can say about it.

SHEILA HETI

What you’re saying is making me think that part of what’s interesting and funny about the joke is that he’s giving a conscious voice to his unconscious understanding of, “Well, I need the eggs.” It’s weird to hear someone be able to speak aloud their unconscious.

GOLDMAN

That feels right to me, and it also makes me wonder about the meaning of the form of the joke. Walter Benjamin talks about Kafka in relation to two components of the Talmud—Aggadah, or narrative, and Halacha, or the law. Benjamin says that traditionally, Halacha is subservient to Aggadah, but that Kafka’s genius is that he sacrifices the truth of tradition for the sake of its transmissibility—so, his writings are parables that abandon or negate the very truth the form is designed to illustrate. It’s almost like Kafka empties the Jewish parable of its content but maintains the form. We could think about this joke as performing something similar—doing what Zohar’s talking about, negating the mystification while also replicating it. Maybe this is where the absurd texture of modernity—and the joke—comes from. Not from saying, “This is irrational, and therefore we have transcended it,” but by being able to puncture or negate the irrational and still not transcend it.

ATKINS

I think what Nathan just said about the emptying out of the content but the preservation of the form is such a great description of what Woody Allen does in general, and of his use of intellectualism as a kind of superficial fashion. The characters will be reading McLuhan or Tolstoy or whatever, and you get this feeling of being so intelligent by participating in it—or at least I did as a teenager—and meanwhile the characters are completely idiotic. But that’s as old as philosophy itself. The philosopher always has to hold herself in suspicion of being a sophist. And maybe that’s the ambivalence—Do we get wiser from art? Or is art just another prop by which we justify ourselves in our psychopathy? I don’t mean that to sound cynical, because I need the eggs, obviously. That’s why I’m here.

DAVID HETI

Yeah. I mean, I do think you can take a joke and break it down into its formal logic. You can say, Here is the proposition, and here is where the contradiction lies. But also, for it to be a good joke, it can’t just be a formal mechanism. That’s how the performance of it matters—in its relation to greater social values, and even in terms of what we understand that one gets out of a relationship. Certain relationships can be purely monetary. A relationship in the old world might have existed only so that both families could survive. You would bring together a farm and get—whatever, a goat or something, whereas now relationships are supposed to provide you with your entire world. So, with the eggs—maybe it’s not even a joke, maybe it’s in fact some ancient story, where the eggs were literally eggs. He needs the eggs!

KHAWAJA

Oh, I love that!

(Laughter.)

SHEILA HETI

It wasn’t even a joke originally! Two hundred years ago there were no metaphorical eggs in a relationship!

ATKINS

Wow! Wait, so maybe the brother really is crazy, but he also does offer eggs!

KHAWAJA

That’s great!

ATKINS

Can I just give you two other associations that came to mind about the eggs? One is that in Jewish law, an egg is a Halachic measurement—it’s a stand-in for a threshold amount by which something becomes substantial. There are actually two different measurements—something is the size of an olive, or something is the size of an egg. Certain things become things at the size of an olive, and others only become a thing, legally speaking, at the size of an egg. There is something iconic about an egg in Jewish law. So if the egg is the minimal amount by which something becomes real, it’s a kind of border, an image of a borderline; yes, it’s a delusion, but it’s a delusion with enough gravitas to become real, to substantiate itself.

SHEILA HETI

That makes me think that a romantic relationship doesn’t become real until it becomes completely absurd to participate in it.

ATKINS

Oh, amazing. And there’s another association. In the Zohar, the book after which I’m named, there’s a short passage on one of the biblical laws, which says to “shoo away the mother bird before taking her eggs,” because it’s considered cruel for the mother bird to be present when you’re taking her eggs away. It’s one of the only commandments in the Torah where reward is given for observing that law, and the reward is that your days will be lengthened. In the Zohar, they interpret it allegorically. The bird is God and the eggs are the manifestations of God, so to shoo away the mother bird and then take her eggs is to say that we cannot know the origin of things, and that we shouldn’t try. But we can know the children, or we can know the offspring, in some form, and we’re allowed that. It’s not just that we’re allowed the eggs, but that inasmuch as we’re obliged to shoo away the mother, we’re obliged to take the eggs. The way I read it is that the eggs represent science or the pursuit of knowledge. The mother bird represents mysticism, and this mystical text is saying, Don’t try to be a mystic, because you’ll fail. But if you admit to the humility of your endeavor, then the eggs here are fine to take. There is a connection—between bird and egg, or between metaphysics and the known life of dailiness—but don’t interrogate it too much. So I think, actually, the mystical, acid-trip take, is, Oh, and the brother actually is a chicken. But it’s not for us to live on that plane, so don’t go there. Just take the eggs. You’re never going to figure it out.

Zohar Atkins is a rabbi, poet, scholar, and podcaster.

Nathan Goldman is the managing editor of Jewish Currents.

David Heti is a stand-up comic of two comedy albums, It was ok and And you will regret it.

Sheila Heti is a novelist and the former interviews editor of The Believer.

Noreen Khawaja is the author of The Religion of Existence and teaches in the Religious Studies department at Yale University.

Copyright

© The Paris Review