“Throwing Yourself Into the Dark”: A Conversation with Anne Carson

Anne Carson. Photograph by Peter Smith.

Anne Carson and I met on Zoom last October, in the brick-red sitting room of her apartment in Reykjavik, the city where she and her husband, Robert Currie, have spent time each year since 2008. A theatrical set piece painted by Ragnar Kjartansson leaned against the wall. Out the window: the ocean and Iceland’s barren expanse. “America seems so cluttered, vegetatively,” Carson said. “Trees everywhere, plants all over the place, flowers. Here it’s just empty. There’s lava, there’s the sea. There’s just lines. Empty space.”

Empty space is one of Carson’s creative playgrounds. “Lecture on the History of Skywriting”—the centerpiece of her latest collection, Wrong Norma—is narrated by the sky, or space itself personified. Formally, where other Sappho translators have filled the gaps between the ancient poet’s fragments, Carson’s If Not, Winter marks the negative space with brackets, emphasizing that lines and stanzas have been lost to history. Carson has often explored absence-as-presence: Eros the Bittersweet argues that desire comes from lack, while Nox, an elegy for her late brother, Michael, mourns the final absence of someone who had long been missing from her life.

We were there to talk about Wrong Norma, Carson’s first original work in seven years, which she called “a collection of disparate pieces, not a coherent thing with a throughline or themes or a way you have to read it.” But images, phrases, and ideas recur: bread, blood, pebbles, a fox, lawyers, a heart of darkness, John Cage, the word wrong, and various flavors of wrongness, for example. “I don’t have much to say,” Carson remarked. Yet over a pair of hour-long conversations, we found plenty to talk about.

INTERVIEWER

Tell me about the “wrongness” in the title of Wrong Norma.

CARSON

When people ask me, “How are Canadians different from Americans?” I say, “Canadians have one characteristic: they’re polite, but wrong.” All the time, polite but wrong.

“Wrong” I put in the title because, well, because of the Canadian thing. And also, something you always feel in academic life is that you’re wrong or on the verge of being wrong and you have to worry about that, because everything is so judgmental and hierarchical. Getting tenure depends on XYZ being “not wrong” every time you speak. So it’s kind of a mentality I was interested in disabling.

It’s something Simone Weil says in an essay she has about contradiction, because people find contradiction in philosophical texts so perplexing, and she specializes in contradiction. She says it’s a useful mental event, because it loosens the mind. And once you can loosen, you can go on to think other things or wider things or the things underneath where you were. It’s just suddenly a different landscape. And that loosening, I think, is what wrongness allows in.

I could talk about wrongness tomorrow and say an entirely other thing. A person is a prism, you know, and concepts just flash from this to that from day to day.

INTERVIEWER

As I read Eros the Bittersweet, I was thinking about the adage that friends and lovers “speak the same language.” I don’t know if that’s true—it seems more like everyone speaks their own individual language, and there’s this constant act of translation happening in relationships.

CARSON

I don’t think anybody ever knows what another person means when they speak, frankly. It’s more than translation, it’s just throwing yourself into the dark. Language is so very, very personal, private. Weird. I guess you could think of it as translation, that seems like a kind of euphemistic metaphor. It’s probably a lot more hopeless than that. But the effort of speaking as a human is the effort to get past that hopelessness with every sentence.

INTERVIEWER

That seems similar to the idea that the way that one language expresses an idea might never fully translate to another. What happens in that space you inhabit as a translator, between the original work and the translation?

CARSON

I think of it as a ditch, a ditch between two roads or countries. It’s always been interesting for me, the state of mind that the translator arrives at, where they have two languages simultaneously on their brain-screen. And they’re saying something not quite equivalent and they both keep on floating there. Some writers—Emily Dickinson would be the outstanding example—make use of that ditch within their own language. So she’s not translating from another language. She’s translating herself. She writes certain lines and words and then crosses them out and puts another word in, or writes the third word on the side, or turns the paper over and makes another version of the whole thing. And it all exists together as the poem. It’s just a really weird state of mind, to have all that floating, and have it be, have it constitute the poem in its entirety—in its untidy, unresolved entirety.

In translation, this arises in a different way, because you have a text, and it has perhaps certain obvious errors in it. And then you have variant readings at the bottom of the page, which are ideas that different scholars have had over the years to make a better reading where it seems wrong. So you get, again, these possibilities floating in your mind, for the same thing, but different. And they’re all kind of there together constituting the poem. I’ve never known what to do with that. It’s a beautiful event to have the poem in Greek with various readings in English underneath it, and to have all that floating as possibilities for what the guy really said.

I can’t communicate the beauty of that most of the time on a page in a book, or in something called “a translation of x.” There’s no format for that. You can do it sort of on a computer with links and whatnot, side text. But basically nobody wants to be bothered with reading all those links, and it doesn’t feel the same. As a scholar, when you’re looking at the page itself with the language and the variants, and it all floats in your mind, it’s just an extraordinary experience. Incommunicable, I think, in its finer aspects.

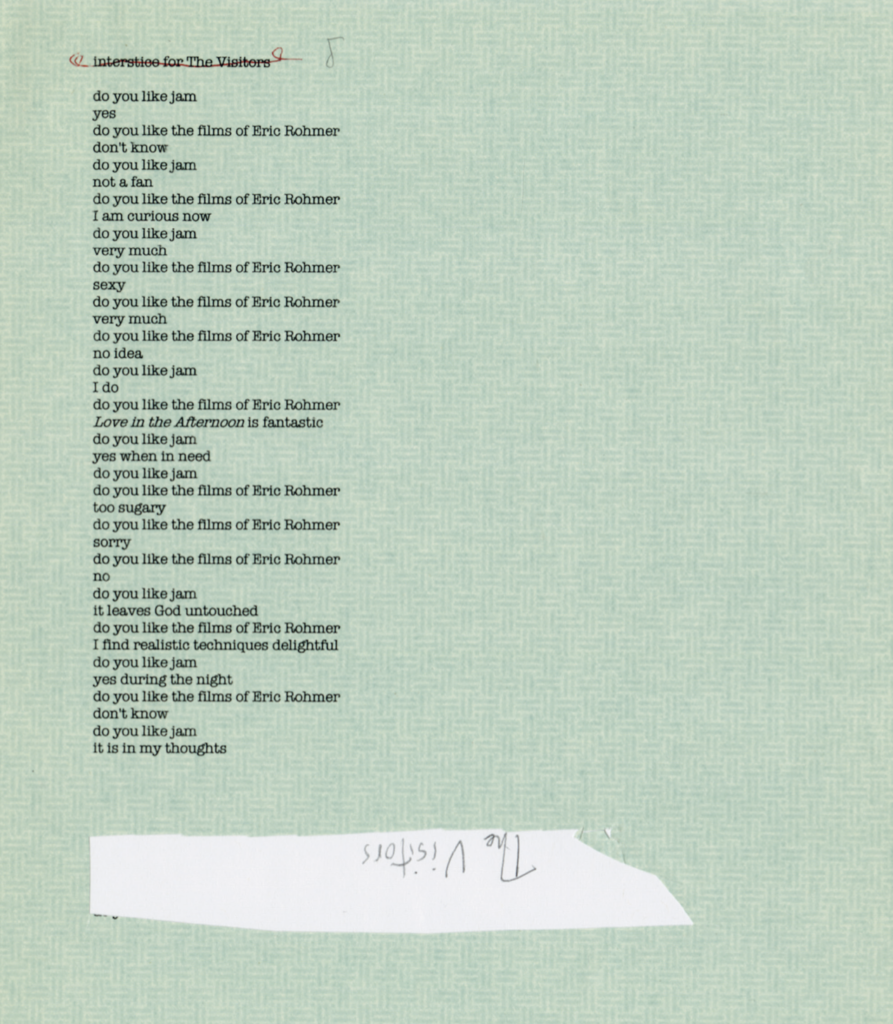

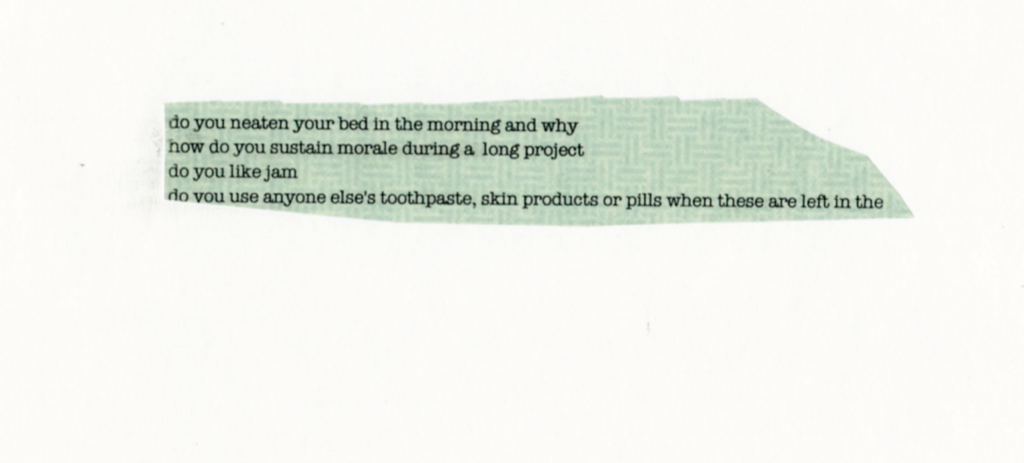

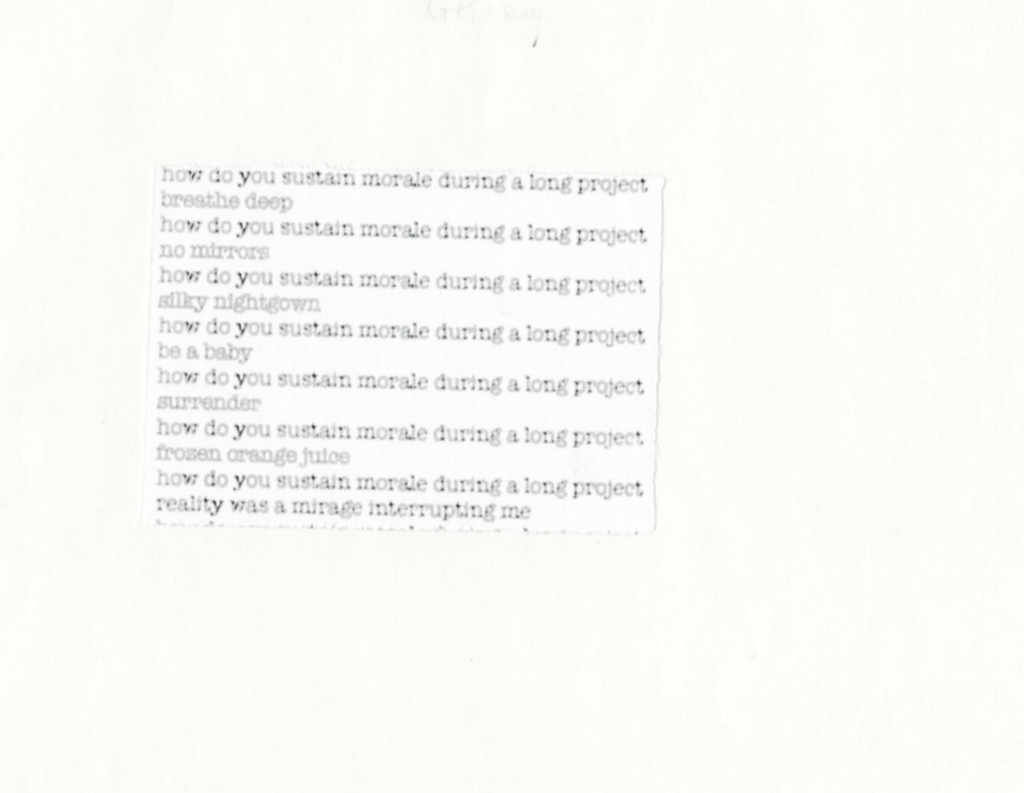

Interior from Wrong Norma.

INTERVIEWER

What about the act of creating something from scratch? Is that experience similarly spatial?

CARSON

I think about it as something that arrives in the mind, and then gets dealt with if it’s interesting. It’s more like a following of something, like a fox runs across your backyard and you decide to follow it and see if you can get to where the fox lives. It’s just following a track.

INTERVIEWER

The fox is one of the mysteries of Wrong Norma. Did he have a fixed meaning or feeling as you wrote about him, or would it change every day?

CARSON

I don’t know where that fox came from. I was writing the liner notes for the LP of Ragnar Kjartansson’s The Visitors, and I was drawing at the same time. The fox appeared in the drawing, and he was such a great fox, I thought, “I’ve got to put that fox in somewhere,” so I put it into the Visitors piece. It was just an accidental fox that arrived by himself and then seemed to need to be dealt with.

INTERVIEWER

How do you access your most creative headspace?

CARSON

Sometimes, what I end up writing about is just the way the light is. And there seems to be some kind of contract that’s already in place between me and the light to say—in this notebook, which no one will ever read—what the light is like today, to get exactly the right words. I don’t know what that contract is. But it seems to underlie all the other writing.

After the light, we could talk about my mother or what I’m having for dinner or Proust’s theory of translation. But the important thing is over. The light was the important thing. It remains a mystery to me why that’s the case, or where that contract came from.

INTERVIEWER

In the piece “Snow,” you write about a premonition featuring the night clerk at the hotel where you stayed the week before your mother passed away. Is that something that happens to you often?

CARSON

Once it did. In Greek myth, the god Hermes is called the psychopomp, which means that when somebody is about to die, he goes to them and leads their soul to the underworld. So I kind of categorized the bellhop in the hotel as that guy. But when Currie and I were going to his father’s funeral, we picked up a hitchhiker in the middle of Michigan, nowhere. God knows where he came from, because it’s just empty landscape and then this guy, on the side of the road, in a really clean blue suit. He had a blue suit and a blue shirt. He was really starched-looking, and he got into the car and the car suddenly smelled like laundry, he was that clean. We tried to talk to him, and he didn’t want to talk. He was going to some public library on the side of the road three towns down, but he wouldn’t describe who he was. And then we let him out of the car at the library and went on our way. That guy was a psychopomp, because we didn’t know Currie’s dad was dead yet. Or, he wasn’t dead yet. He died the same day. We figured that guy was the sign that somebody’s going to the other world. So it does happen. I wouldn’t say often.

INTERVIEWER

For a long time, you and Currie co-taught a class on artistic collaboration at NYU called “The Egocircus.” What sorts of exercises would you do with your students?

CARSON

“Burn something, use the ash” was one of the prompts. “Improve a hotel” was another. We sometimes gave them just three words like “sailing, butter, death.” And then they would make things. It wasn’t that we disallowed writing entirely—they always did come up with writing—but we encouraged them to use other skills. They were always discovering things they could do that they didn’t know they could do.

INTERVIEWER

Do you have any non-writing skills that are part of your writing process?

CARSON

Drawing and painting. I’ll put swimming in. Tidying up, I’m a good tidier.

Interior from Wrong Norma.

INTERVIEWER

How does swimming figure into your writing?

CARSON

It keeps me from being morose and crabby. Sometimes I think in the pool. Usually it’s a bad idea. The ideas you have in the pool are like the ideas you have in a dream, where you get this sentence that answers all questions you’ve ever had about reality and you get up groggily and write it down, and in the morning, it looks like “let’s buy bananas” or something completely irrelevant. Plus, I like water. Some people just need to be near water.

INTERVIEWER

You and Currie are fans of John Cage, who talks about eliminating the ego from art. I’m still thinking about the John Cage epigraph that appears in your 2016 collection Float—“Each something is a celebration of the nothing that supports it.”

CARSON

That pertains to writers because they tend to have an accumulated store of memories and choices, which they call their autobiography, and then they just recycle that endlessly as they’re writing. You’ve just got to get out of that.

INTERVIEWER

In the writing world, particularly in and around M.F.A. programs, there’s a lot of discussion around things like “character” and “perspective,” the mechanics of narrative. Do you think about “craft” in these terms?

CARSON

Never. I don’t think about it. I think people should just quit that stuff. Just think about something and follow it down to where it gets true.

INTERVIEWER

I worry that—in America at least—the act of critical thinking is being devalued from a cultural perspective. Do you notice that as a thinker or teacher?

CARSON

That’s part of the thing that made me start thinking about hesitation. The last few years I was teaching, I was teaching ancient Greek part of the time and writing part of the time. And the ancient Greek method when I was in school was to look at the ancient Greek text and locate the words that are unknown and look them up in a lexicon. And then find out what it means and write it down. Looking up things in a lexicon is a process that takes time. And it has an interval in it of something like reverie, something like suspended thought because it’s not no thought because you have a question about a word and you attain that as you go through the pages looking for the right definition, but you’re not arrived yet at the thought. It’s a different kind of time, and a different kind of mentality than you have anywhere else in the day. It’s very valuable, because things happen in your thinking and in your feeling about the words in that interval. I call that a hesitation.

Nowadays people have the whole text on their computer, they come to a word they don’t know, they hit a button and instantly the word is supplied to them by whatever lexicon has been loaded into the computer. Usually the computer chooses the meaning of the word relevant to the passage and gives that, so you don’t even get the history of the word and a chance to float around among its possible other senses.

That interval being lost makes a whole difference to how you regard languages. It rests your brain on the way to thinking because you’re not quite thinking yet. It’s an absent presence in a way, but it’s not the cloud of unknowing that mystics talk about when they say that God is nothing and you have to say nothing about God because saying something about God makes God particular and limited. It’s not that—it’s on the way to knowing, so it’s suspended in a sort of trust. I regret the loss of that.

Interior from Wrong Norma.

INTERVIEWER

Do you think that our experience of time has something to do with the way that we pay attention? Do you think that someone who reads a lot would experience time differently from someone looking at screens all day?

CARSON

That seems to imply judgment. I’m not sure. What I am sure of is that we seek out ways to make time stop. That only happens in moments of total attention, which is why we pursue them. I suppose that can happen when you watch a movie on Netflix. Or when you’re deep in the midst of composing your best poem. Either of them can provide a focus of attention that you can enter, disappear into. My only interest in dealing with time is to find ways to make it stop. Because when it doesn’t stop, you’re in boredom.

You’re watching it go by, and there’s nothing happening in it enough to fill it. Enough to take you away from misery. I don’t find much of a middle ground between boredom and whatever the other thing is … immortality, I guess. Forgetting time.

To be out of time, to be in that other state, is completely fun. So fun that you forget worrying about time.

INTERVIEWER

Do you spend hours at a time in that state?

CARSON

Minutes maybe, if I’m lucky.

Kate Dwyer is a writer based in Brooklyn. Her work has appeared in the New York Times and many other outlets.

Copyright

© The Paris Review