There Are No Minor Characters: On Jane Gardam

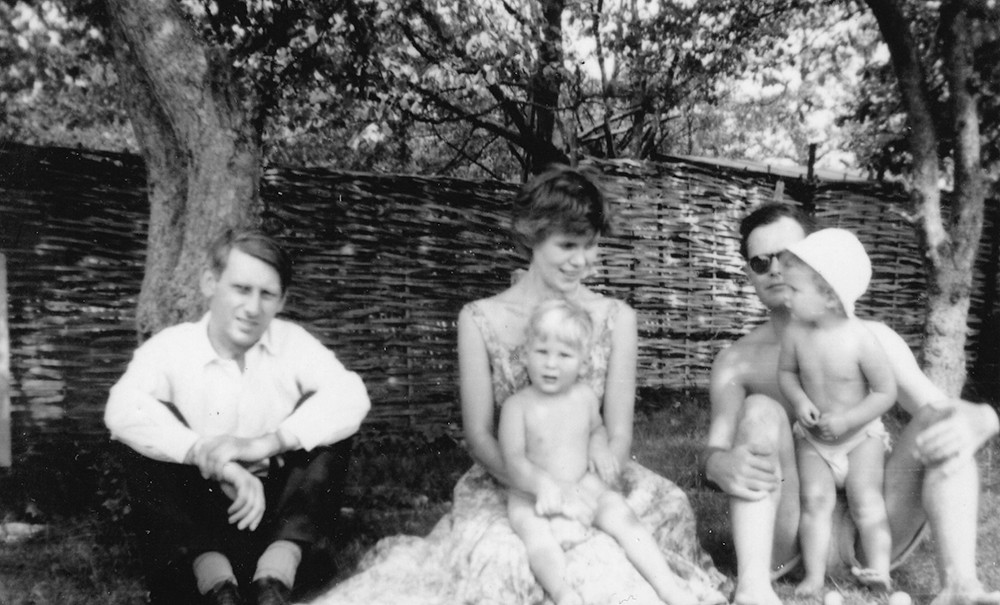

JANE GARDAM WITH HER HUSBAND, DAVID, HER SON, TIM, AND FAMILY FRIENDS, 1957. Photograph courtesy of Jane Gardam.

You should read Old Filth, someone said to me about ten years ago. I couldn’t for the life of me, in true Gardam fashion, remember who that friend was until just now—it was the writer Nancy Lemann—but I can think of the people—dear friends—to whom I went on to recommend it myself. I adored the book, stunned I had not heard of Jane Gardam before, and immediately read the next two books of the trilogy: The Man in the Wooden Hat and Last Friends. I then taught Old Filth in a seminar so that I could spend more time with Gardam and study more closely how she creates her magic. She improves, as great writers do, upon rereading. And then reading again.

I found out more about her life. She published her first book at forty-three, and was a mother of three children. In the next thirty years she published twenty-five books: many collections of short stories and many books for children. She was seventy-six when her masterwork Old Filth was published and eighty-five when Last Friends came out. She says that she wrote to survive, working in a green room overlooking her garden, since during this time both her daughter and husband died, her husband having suffered with dementia for several years.

She says that when she first started writing—the morning after she’d dropped her youngest son at his first day of school—she was not interested in what was fashionable or what was publishable. She just wanted to write. She believes that there are no minor characters. Everyone’s as interesting as everyone else.

Gardam’s style combines wit, romance, brevity, and enchantment. As the best artists do, she offers hard truths in a pleasurable way. There is no overindulgence. Sensuous details are side by side with a sharp intelligence. She is the master of the quick brushstroke, painting a room, a city, the feeling of an era, or simply a complex-at-one-glance character. Philosophical musings merge into social commentary, but you notice no intrusion because you are mesmerized by the story. The story is everything. An omniscient voice plays alongside a character’s point of view; there is lightness in tragedy and depth in comedy. A description of Betty Feathers, from the trilogy, could very well apply to Gardam:

Amazed as she never ceased to be, about how such a multitude of ideas and images exist alongside one another and how the brain can cope with them, layered like filo pastry in the mind, invisible as data behind the screen … Betty was again in Orange Tree Rd standing with … old friends in the warm rain, and all around the leaves falling like painted raindrops.

Gardam is interested in the passage of time, in generational shifts and in ecstasy. Over and over she presents to us the surprise of things, the surprise in people, in the world. Over and over we learn the devastation of cruelty and the highest value of kindness. She reminds us that we don’t truly know anything, but it all remains endlessly interesting.

—Susan Minot

At the beginning of April 2020, my husband and I went upstate with friends for an indefinite period of time, to avoid other people and to bleach boxes of cereal. We ended up staying for three months, and in those three months I read every novel, and almost every short story, that Jane Gardam ever wrote. Though I had read Old Filth a few years earlier and loved it, I had not picked up her other books. It was as if some clairvoyant part of myself knew to save them for a world-historical catastrophe.

Liking to read is an unearned privilege along the lines of beauty or wealth or an American passport, an advantage that makes a life easy in ways that one should feel grateful for all the time but seldom remembers to be. Jane Gardam reminded me to feel lucky. I was not bored or lonely or anxious while in her company; there was nowhere really I wanted to be other than with her. This is a perfect mind, I remember thinking to myself, over and over again during those strange months: How is she doing this?

Gardam’s writing is hard to write about. The adjectives I’d use to describe her work—comic, quiet, moving, perceptive—are, unlike their more obvious counterparts—funny, sophisticated, heartbreaking, clever—not qualities that reveal themselves in single sentences. This is why, in over a dozen volumes sitting on my bookshelf, not one page is marked. The relative felicity with which I am able to identify what I like about other books makes me suspect that Gardam’s are better.

—Alice Gregory

It used to be said at the Bar of England and Wales that the Queen would not let any of her counsel starve. What this signified in practice was that being appointed one of her Majesty’s counsel learned in the law (and thus a QC—more readily known, after the associated apparel, as a silk) was a riskier business than it seemed. For most barristers it opened a gate to higher fees, more prestigious work, and possible elevation to the bench. But for a few, despite proven ability, it turned out to be a dead end: good work simply didn’t come. For these practitioners the lord chancellor would always find a county court or tribunal chair appointment. They would never starve. In fact they included some of the ablest county-court judges of my early years at the Bar.

Not all Queen’s counsel, anyway, wanted domestic appointments. The colonies, Hong Kong among them, offered both well-paid briefs and occasional seats on the bench. Hence the acronym famously devised by Jane Gardam for those who had failed in London and were now trying the colonies. Such a sobriquet would have been used not by the metropolitan profession (it would have been insulting) but by way of ironic self-deprecation by those Tennysonian advocates—Jane Gardam’s exquisitely delineated heroes and villains—who set off for lands beyond the sunset, determined to make a go of it. Many did.

In the course of time they were supplemented, even supplanted, by London silks flown out for prestigious cases and required as a formality to be called to the local bar. I happened to be lecturing in Hong Kong when this particular edifice began to totter. A highly regarded London-planning silk had been brought out for a hearing on which a great deal of money, though not a lot of law, depended. The newly installed chief justice refused to call him to the local bar: It was, said Yang, a case which any competent local practitioner could handle. The locals and the expats cheered. Old filth indeed!

—Stephen Sedley

I can’t tell you the moment I became absolutely certain the Review had to do an interview with Jane Gardam, although I can picture the room I was in. I have described her as “not cozy” before, and as “underrated,” and as “strange but not weird,” but those are things Gardam is not. (And she is rather elusive.) I can call her writing only bracing: unsentimental, yet not without heart and a sort of brisk belief in both people and higher things. She’s got the keen eye and the ruthless judgment of a true artist, but she sort of just gets on with it. On the surface, the books are (for lack of a better word) accessible—they are not hard to get into, or through. But they stay with you, and reward serious reading.

She writes children with great respect. That’s true of anyone writing well for young people—she wrote several novels for young adults—but it colors her adult work, too. I think of that as something English writers are good at, now that it occurs to me.

And, of course, her relationship to the geographical landscape colors everything and is highly specific. There are questions—and micro questions—of class, geography, and education that are almost certainly lost on me as an American reader, but the fact that the books can still have a powerful effect speaks to the sheer quality of her writing.

—Sadie Stein

Susan Minot’s eighth book, Why I Don’t Write and Other Stories, was published in 2020.

Alice Gregory lives in New York. She is at work on a book about the artist Robert Indiana.

Stephen Sedley practiced at the Bar of England and Wales from 1964, taking silk in 1983. He was appointed a high court judge in 1992 and a lord justice of appeal in 1999, retiring in 2011. He has written on law for the London Review of Books since 1986. His volume of essays, Ashes and Sparks, was published in 2011.

Sadie Stein is a New York–based writer and critic. She interviewed Jane Gardam for the Spring 2021 issue of The Paris Review.

Copyright

© The Paris Review