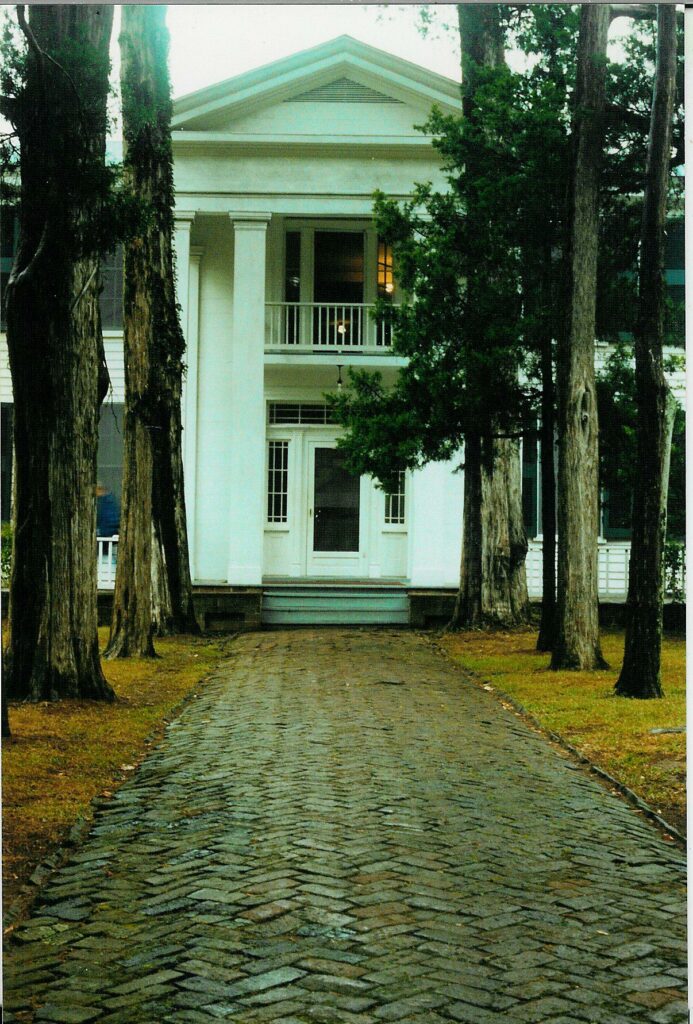

“That’s the one trouble with this country: everything, weather, all, hangs on too long,” William Faulkner wrote of his native Mississippi in his novel As I Lay Dying. “Like our rivers, our land: opaque, slow, violent; shaping and creating the life of man in its implacable and brooding image.” There came a day when, as a reader of Faulkner, I wanted to see what he was talking about. If the tendency of things in Mississippi was to hang on too long, as Faulkner claimed, maybe the populace and the landscape would be more or less the same as they’d been when he wrote those lines in 1930. The drive from Brooklyn to his house, Rowan Oak, in Oxford, Mississippi, was seventeen hours.

Five hours in, I made a pit stop at an abolitionist holy site: the federal armory at Harpers Ferry, West Virginia. John Brown’s raid on the armory, in October 1859, was one of the proximate causes of the Civil War. It enraged a plantation-owning class already frightened of northern agitators. “I want to free all the negroes in this state,” he said, referring to Virginia, where half a million people were enslaved. His plan was to seize guns and hand them out to men in the nearby fields, fomenting rebellion. With twenty-one followers, he stormed the armory and held parts of it for two days before U.S. marines flushed him out. All that’s left of the armory, mostly destroyed in the subsequent war, is the fire-engine house, which happened to be Brown’s final redoubt. He was captured there, and then taken to prison, tried, and hanged. I stood in the house; it’s the size of a two-car garage, dwarfed by the green, misty mountains that surround it. It drove home how tiny Brown’s force was, for it to have been able to fit inside such a small place—how inadequate to his stated task.

In Faulkner’s novella “The Bear,” John Brown appears without warning, in the middle of a stream of consciousness, and has a dialogue with God. He explains to Him that he, Brown, is unusual among men only in that he sees slavery for what it is, a “nightmare.” God asks, “Where are your Minutes, your Motions, your Parliamentary Procedures?” Brown responds, “I ain’t against them. They are all right I reckon for them that have the time.” Note that Faulkner makes God sound lame and officious, and gives Brown, an Ohioan, the locutions of a backwoods Mississippian. As a man of action, and as a person who acknowledges the true nature of things, Brown is a kind of honorary Southerner.

Faulkner called Lafayette County, his home, “the final blue and dying echo of the Appalachian mountains.” This is true. I followed the spine of the alpine chain southwest from the peaks of Harpers Ferry, where the weather was cool and pleasant, down through Tennessee, until the mountains dribbled away in the heat of northern Mississippi. Lafayette County was the last place where the hills were substantial. I drove an additional hour west to see the Delta, which was flat, consistent with its reputation. Then I turned around and drove to Oxford.