Roadrunning: Joshua Clover in Conversation with Alex Abramovich

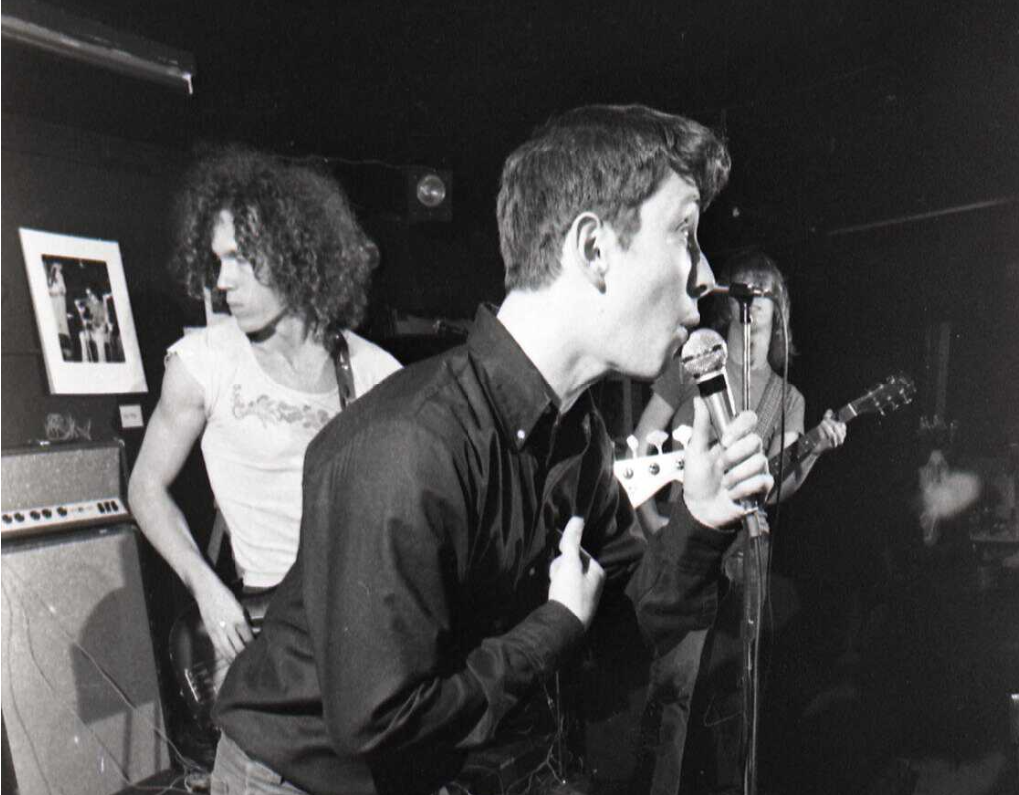

Jonathan Richman around 1972, with Modern Lovers, Department of Special Collections and University Archives, W.E.B. Du Bois Library, University of Massachusetts, Amherst.

What follows is part of an email exchange between Alex Abramovich and Joshua Clover about Jonathan Richman’s song “Roadrunner.” Their conversation takes the scenic route, beginning with a materialist definition of rock ’n’ roll and ending by arguing over the Velvet Underground (too ironic? Too elitist?). Along the way, they touch on the nature of influence, poetry versus criticism, art versus revolution, the specificity of rock ’n’ roll freedom, and what it means to drive with no way out.

Dear Joshua,

I’ve been thinking a lot about the talk you gave recently as part of the “Popular Music Books in Process” series. I loved this talk because the definitions of rock ’n’ roll that it points to are so obvious, simple/not simple, and right. Quoting selectively, starting at about the six-minute mark:

There are ten thousand freedoms but rock freedom is definitely set—in the first instance—in a car, when it’s late outside. It can be ecstatic, it can be boring, it can be adjectiveless, but you have reached escape velocity, faster miles an hour, you have no particular place to go, and you have the radio on.

If you did have a particular place to go, that is to say, if you were not free, where would it be? That may seem impossible to answer but in some sense I think it is schematically clear. It’s important to remember that rock ’n’ roll is truly an invention of massive industrial growth. That provides the key. You are free at the wheel of your automobile because of a complementary unfreedom, which is, to simplify, the person working in the auto factory. When you buy the car you are purchasing their misery. And the important thing is, the driver and the factory worker, one circulating through the world of consumption with its pop songs and Stop & Shops, one immobilized in the world of production with its assembly line … these are not different people, despite what they tell you in Econ 101. They are the same person, it’s just a different time of day.

I should stop here and say at the outset (as you do in your new book, Roadrunner) that the first version of “Roadrunner” was recorded in 1972—just before “the collapse of manufacturing and industrial profits, the tilt from Boom to Bust, ruination for the postwar compact of Bretton Woods, oil shock and oil crisis, stagflation, the hollowing of the labor movement, final humiliation in Vietnam, and on and on” of 1973. It’s a pivotal moment: peak America. A few years later, Neil Young’s going to release On the Beach: the album has the ass-end of a Cadillac sticking out of the sands of the westernmost part of the nation.

The end of the road.

But, as you also point out, the road Jonathan Richman’s on (Route 128, around Boston) is a beltway—a road with no end:

Even if you are not literally an autoworker, this structural relation, this contradiction, is still 100 percent in place. You are still part of the vast class that has to labor to buy back the very things it produces—at a premium. That spectral freedom of the highway is inevitably purchased with your own unfreedom. The ring road always turns away from the factory, from this truth. And because it’s a ring road, it always turns back toward it, too.

It’s fascinating, the ways economics and culture keep bleeding into each other. Your book looks back, not just to Chuck Berry, but to the Federal Highway Act. It looks forward, not just to Cornershop and M.I.A., but to Long-Term Capital Management, the War on Terror, Tyson Foods, Tamiflu, the Tamil Tigers and, finally, COVID-19. But it’s not really criticism, is it? Here’s a note that I made: “It sounds a lot like music criticism but, in reality, Joshua’s doing theory. Or so he thinks. Because what he’s really doing is poetry.”

Would you disagree with that? Or are those distinctions now without a difference? I’d love to hear a bit about your method.

Lastly, since we’re discussing freedom in the rock ’n’ roll context, I’m wondering what you make of that old Michael Lydon article in Ramparts; the one where he says that rock ’n’ roll isn’t and can’t be “revolutionary music because it has never gotten beyond articulation in this paradox [the obvious pleasures America affords/the price paid for them]. At best it has offered the defiance of withdrawal; its violence never amounting to more than a cry of ‘Don’t bother me.’” I’m also reminded of the incredible Ellen Willis piece on Woodstock. To what extent (if any) is your book a discussion, or argument, with those perspectives?

As ever,

Alex

***

Dear Alex,

You give me too much credit, though that’s not your fault; it may be an artifact of my approach, arguably my hubris. When I started out, I am not sure I had clear-headed plans. I just thought that having to make a book out of a four-minute song was a formal problem asking for solutions that would be interesting or would bomb or both, especially given the constraint that I had no intention of engaging in much of the biographical, autobiographical, or academically musicological. What did that leave me with? History, or my obsessions. These are pretty close together. Since the 2008 economic collapse and the global political ferment that followed, most of my thinking and writing, whether it be scholarly or in more public writing or even in anonymous and collaborative screeds, has been about crisis, particularly the long crisis of American capitalism that I date to around 1973, and about how its transformations—notably toward intense and desperate strategies of circulation for profit-taking—shape how people fight to get free.

I didn’t choose “Roadrunner” because its recording timeline and its image of a person literally circulating through the night allowed me to discuss these things. I chose it because it’s magic. I have felt its magic for a long time but never had a good story about it. And because I couldn’t figure out a path to a book about “Tell Me Something Good,” a song at least as magical. That book goes “Something something—wait! Did you know that Chaka Khan got the name ‘Chaka’ when she joined the Black Panther Party for Self-Defense in Chicago?” And I am not sure I know how to tell that story in a way that does justice to Chaka, and Rufus, and the BPPSD, and Chairman Fred. So there I was with “Roadrunner.” And once I set out along Route 128, there was no way for me not to situate it within what is for me the true metanarrative of the U.S. present: the catastrophic trajectory of capitalism.

And the thing about capitalism, you know, it has to expand just to stay even, just to keep functioning, capitalists as a whole have to be able to turn money into more money or they’re out. And that means two things, immediately. One is that it has to dominate more and more of the planet, more and more of our lives. People sometimes complain that Marx’s thought “totalizes,” that it draws everything into its logic, which is … a confusion. The thing that totalizes—the thing that is compelled to draw everything into its own logic, its own circuits—that’s capitalism itself, that’s its inner character. Marx is just narrating that action, he’s not making it happen. The other thing about this compulsion to expand is that, when it can’t do that anymore, it enters into crisis. The end of growth isn’t just a lull, it’s a disaster that we’ve been living through for fifty years and one that isn’t going to reverse.

Okay, so that’s the theory part. The poetry part is finding a language for it. I wanted to find a form—spoiler, it’s basically the run-on sentence—that was at once true to the particular motion of a car going around and around, going past this and that without ever stopping, and also true to the general motion of expansion that wants to go out toward everything, that can’t resist trying to bring in everything. So, a run-on, but increasingly full, not, er, running on empty. Anyway you’re generous to suggest that the book confuses poetry and theory, as it might be the case that it merely confuses style with history.

But if I knew from this history that I would be starting the book near the onset of the long crisis that opens onto the present, I definitely did not know that I would also leap backward into the heart of long postwar boom. I had no idea I was going to go back to the source, and end up proposing my own version of, “Here’s what rock & roll really is, man.” Maybe it is inevitably true that if you have a theory of the end you end up with a theory of the beginning. That’s the ring road. Anyway, trying to get my head around that was exciting and daunting and I loved writing that chapter. But that is also the moment of hubris, inevitably, and of exaggeration. I believe what I said, it’s pretty easy to convince yourself as you go, but let me take at least one step back. Even if you buy my pitch, the limit of this exaggeration is, I make claims only about what rock is. I am a materialist. I don’t think rock does much outside the world of representation, ditto poetry and movies and video games. It is an account of the world in inverted form. And rock became for a while the orienting type of popular music because it got at something vast and true. It knew the terrible thing and still it sang. And I love listening to the truth at 45 rpm, even when it is upside down.

But now let me bring it all back home. I am grateful to be compared to Lydon and especially to the great Ellen Willis, but I should demur. They are among other things reflecting—especially Lydon—on rock’s failures to do what it seemed to promise. To me that’s in par with chiding, I don’t know, Bororo myth for failing to be revolutionary strategy. Like, you don’t say! Blaming rock for failing to play a role in changing the world is akin to blaming Marx for the fact that capitalism is totalizing. Rock just says a truth about the condition of the world, it doesn’t bring it into being. It’s surely true that the generation of Woodstock didn’t make the rev. That’s on them, not on Jefferson Airplane except in so far as Paul Kantner failed to join Weather Underground. And if we fail, that’s on us. But if we succeed, it happens on the Standing Rock reserve, at the John Deere factory, in the streets of Oakland. And then there will be songs.

***

Joshua,

I did not know that about Chaka Khan! But Jonathan Richman at Town Hall was the last concert I saw before New York went into lockdown. The friend I saw him with didn’t like that concert—and it didn’t help that Will Oldham came out and sang at some point. Oldham is sort of Richman’s opposite, right? Everything held at a tremendous distance; a walking definition of irony (although, I would argue, the home recordings he made in lockdown were the opposite of that). Afterward, Dan and I went over to Jimmy’s Corner—the old boxing bar off Times Square, which was closed for most of the pandemic and reopened just a week or so ago. Once we’d gotten our drinks, I did my best to convince him, “No, no. That wasn’t an act. Jonathan Richman’s the most sincere artist who ever lived. There’s so much purity, goodness, and joy.”

Did I convince him? I don’t know. Maybe it was a dumb argument, like the one you and I had earlier this year about the Velvet Underground. The way I remember that is, I’d said “Something, something, ‘Sister Ray.” And you’d said, “Oh, no. Richman and ‘Roadrunner’ have nothing to do with VU.”

Obviously, this is absurd. There’s the biographical part: Richman saw eighty Velvet Underground shows—he’s the reason that band played so often in Boston. He practically lived with the band. He’s all over that new VU hagiography Apple keeps trying to get me to watch. There’s the musical part. John Cale produced the original recording. When it comes to the chord structure, instrumentation, arrangement, et cetera, “Roadrunner” is pretty much a cover of “Sister Ray,” isn’t it?

You dismissed all that, if I recall, on the basis of you just don’t like—in fact, hate—the Velvets. And so, we started to argue that: You said they were elitists, and the fount of elitism in rock.

I said: “Well, they weren’t elitists. How could they be? Didn’t they sing for the outcasts? Weren’t they outcasts themselves? It’s not their fault that elitist schmucks came in their wake. That’s like Michael Lydon or Ellen Willis blaming rock and roll music for the failures of the sixties. If anything, the anti-elitist position you’re staking out now is as elitist as anything else.”

Unless I’m mistaken, you see VU as arch and ironic—diametrically opposed to Richman’s sensibility—and so, you look past VU and go back to Chuck Berry. I don’t see VU that way all but, of course, you’re not wrong: all roads really do lead back to Berry. Not only is “Subterranean Homesick Blues” the same song as “Too Much Monkey Business.” Another Chuck Berry song (about, you guessed it, going down the highway at night) is the father of “Come Together,” by the Beatles, “1970,” by the Stooges,” and two songs (“State Trooper” and “Open All Night”) off the only Springsteen album that I truly like. He was not sui generis, but who is?—so, of course, start with him.

Moreover, grounding your argument in Chuck Berry sets you firmly in the world of cars (the place where rock and roll freedom, in that first instance, is set). A freedom whose flip side is Fordism and alienation. There’s a difference, I guess, between Berry’s driving songs and “Roadrunner” in that Berry always seems to be going down the open road. It’s still the fifties; the economy’s still expanding; we can still cling to ideas of expansion and progress. Worse comes to worst, we can always go west. (Or so the fantasy goes. In real life, just a few days before the end of the fifties, Berry was busted and imprisoned for violating the Mann Act: specifically, for transporting a fourteen-year-old girl across state lines. Which is to say, he lost his own freedom, in part, because he was driving while Black.)

But I can’t help thinking of “Rock and Roll“—a song that makes room for “two TV sets and two Cadillac cars” (albeit garaged), and casts a cold eye on the commodities we surround ourselves with (to make up for all the ways capital fails us) while making bold, explicit claims for the soul-saving, revolutionary potential of … rock ’n’ roll? Lyrically, it’s much closer to “Roadrunner” than “Sister Ray” is. It seems at least as relevant because it’s such a clear example of ways rock does make promises having to do with freedom:

You could dance to a rock and roll station … and it was alright …

She started dancing to the fine, fine music—her life was saved by rock and roll…

To me, that’s the whole kit and caboodle. Just those words, saved and alright. They’re so … loaded. In the Holiness church, Lou Reed’s favorite refrain (“I feel alright”) meant a specific thing: you’d gotten happy. You were possessed, now, by the Holy Spirit.

In that moment, you were free.

Rock ’n’ roll turned some of that on its head. It kept the building blocks, starting with the backbeat. (“I was raised in the Holiness Church,” Lionel Hampton wrote in his memoir. “I’d always try to sit next to the sister with the big bass drum. Our church had a whole band, with guitar, trombone and different drums. That sister on the bass drum would get happy and get up and start dancing down up and down the aisles, and I’d get on her drum: boom! boom! That heavy backbeat is pure, sanctified, Church of God in Christ.”) The songs still had to do with ecstasy (literally, a “standing outside of oneself”). But now, through some weird, self-reflexive trick of the light, rock ’n’ roll itself was the vehicle that delivered us there. Rock itself became the answer to problems that life in industrial society presented. (“I’m gonna rock, rock, rock/rock my blues away.”) It promised and, in theory, it seemed to deliver.

But in practice, the freedoms that rock ’n’ roll offered turned out to be much more transitory. Things are alright, for a while. Then we get older and start listening to Steely Dan. (I’m partial to The Royal Scam myself.)

That’s what Lydon and Willis were getting at, I’d imagine: rock songs do promise something. Maybe something as simple as, “you don’t have to grow old.” And they fail us, and maybe they fail because they don’t know the terrible thing, after all. (The terrible thing being, we do grow old, and the factory awaits us all.)

I still think we’re on the same sort-of side: “Roadrunner” is the perfect song for you to have written about, because it never does make that promise. It describes the things Jonathan sees on that ring road, and the way those things make him feel, and there’s a soundtrack (“radio ON!”), but there’s no destination; just the going around and around and around, staying in that churchy, Velvety back-and-forth I-IV chord progression that never resolves.

As you said in your talk:

I do my best to re-narrate something like the founding myth of rock and roll, which I sometimes call the “ur-story.” And it goes something like this: It’s about freedom. I know that is impossibly corny, but I hope you’ll stay with me out of generosity alone. I think “Roadrunner” is worth a book because it’s the truest telling of this ur-story, this myth. The song is so minimal because it is really committed to refining this inner nature down to its essence. With its two or three chords, and nowhere to go—that is to say, its utter constraint—“Roadrunner” is the freest song I know. Anything could happen next. And doesn’t.

I guess what I’m saying is, Jonathan does know the terrible thing, He knows, and that’s why he never gets off the ring road. Personally, politically, there’s nothing there for him—so he stays. And he never grows up. Which, to go back to biography, is just what happened: Jonathan never grew up. That’s what I was trying to get Dan to believe, back at Jimmy’s Corner. If ever there was a true Lost Boy, it’s him. If ever anyone was delivered by “Rock and Roll” (the song, as well as the music) it’s Jonathan Richman. But, I am guessing, it came with a price.

Alex

***

Dear Alex,

Welp, I guess we’ve gotten to the part where I alienate all of our readers. Clearly we cannot escape the question of the relation between VU and Jonathan Richman. I have a lot to say, but I hope to think less about which act one prefers (though this would be disingenuous to ignore) than how we think about influence.

Maybe a good place to start is with “Can I Kick It?” by A Tribe Called Quest. That it has Lou Reed in it is a factual matter; it samples “Walk On the Wild Side.” It is literally in-fluenced: that sound flows in. But, so what? Stuff is made from other stuff. I say this somewhat contra Modernist lore. The double myth of Euromodernism features on the one hand the fantasy of pure originality, of creation ex nihilo: Stein, claiming to be quoting Picasso, writes, “when you make a thing, it is so complicated making it that it is bound to be ugly, but those that do it after you they don’t have to worry about making it and they can make it pretty.” And then on the other hand, we have the Eliotic fantasy of “these fragments I have shored against my ruin,” of keeping alight the guttering flame of white European culture, preserving the line of cultural transmission. So there is the authentic origin, and there is preservationist lineage or heritage—and both sides of this Modernist mythos place an undue emphasis on the unremarkable fact of influence.

But this can’t explain something important. “Can I Kick It?” is, you know, much better than anything Lou Reed ever did. Which should not surprise us, nor should it surprise us if it were worse. It’s not such a big deal. Stuff is made from other stuff, as that collagist Picasso knew perfectly well. The problem arises when you move from the mere factuality of influence, from the fact that materials have sources, to its priority. That’s when it risks obscuring more than it reveals.

So in this regard I think it’s unfortunate that people, especially critics, are so stuck on the significance of the relation between VU and Jonathan. On the priority. I think it obscures far more than it reveals about the bottomless and extensive and mysterious character of “Roadrunner.” I also think it’s basically anti-teenager, as if the adjacency of an elder means Jonathan could not have forged this extraordinary thing without some grand inheritance. As a thought experiment, I encourage everyone to take the terms Richman/VU and swap in Rimbaud/Verlaine. Okay, let me leave Modernism behind for the particular of the case at hand.

I would never say that VU and Jonathan have no relation—they have a profound one that I touch on in the book. It’s factual. And it’s of course about automobiles: for a while Jonathan serves as Lou’s driver, using his dad’s car. But it is also about music: Jonathan absolutely takes in all of that sound as part of his knowledge, as he takes in Chuck and the Beach Boys and so many others. This in and of itself tells us very little. When you make a thing, you make it from all that you know, and if it is extraordinary or even unique this is not because it has no history, no influences, arises out of nothing.

This may seem odd, but for me it’s crucial: to say X is influenced by Y is not to say X is like Y. The character of X, its extraordinariness, comes from its relationship to the everything, what it does with it. And that may even be unique, whatever goes into it.

More often it is not unique. Maybe it is just an interesting rehash which by the way I am fine with, I love pop music and I don’t need art to be some durable lasting objet. But sometimes songs are extraordinary, like “Roadrunner.” And if your understanding of musical relation is chord changes, then sure, you can say “Roadrunner” is “Sister Ray.” If your understanding of musical relation is genetic—there was that music, and then it evolved into this music—go for it. And if your understanding of musical relation is subcultural, where this dude knew that dude and the wisdom was passed down, cool. That’s not really how I understand things. My first obligation is to history. There is not one pair, Richman/VU. There are two pairs, Richman/history and VU/history. Now, how do these two pairs relate? That’s an actual question. And I would argue that VU and Jonathan stand in opposite and even antagonistic relations to history, to the world itself.

VU are super-duper into knowing about the world, recognizing it, classifying it, possessing it in mind and in song. They are the exemplars of this German term Besserwisser, a better-knower. They know better. Their fans know better. They discern. They might like fake I-get-the-joke Warhol pop, pop that knows about pop. But they do not care for pop itself. In the heat of the Top 40 moment, they scorn, say, ABBA, a far more influential band, until enough time has passed to ironize and sterilize the taint of pop. Liking ABBA only twenty years later is the surest sign of a bad character, period. Show me the person who in the moment, in 1976 said, in all sincerity, “Rock and Roll Heart is very lovely album, but I like Arrival a bit more, it’s smarter and more fun, they’re my two favorites,” and I will be very pleased to buy this person drinks all night long.

Fortunately for my Venmo, that person basically doesn’t exist because that is the nature of knowing better. Maybe it is simply a weapon of the weak, of the outcast, to know better. I don’t think so. This was certainly not my experience as a teenager who was particularly interested in social class. Knowing about VU, and being really into them, was just a class marker of private school kids. I am not sure I would use the discourse of elitism, which is so messed up these days, but the role of VU as a prestige-conferring taste…I mean, anyone can claim to be an outcast, I guess? Everybody imagines themselves bullied and not the bully. But the Besserwisser sits near the center of an entire worldview that reviles the forty-year-old woman driving around in her Yaris listening to John Denver, who has more good songs than VU by a margin of two.

I really think all of this is present in your inquiry. “Roadrunner” is about driving through the world, and music on the radio is part of that world. “Rock and Roll” is about … rock ’n’ roll. They know all about it. We can discuss the racial politics of Lou Reed saying “and the colored girls go…” in “Walk on the Wild Side,” which I think leaps out as a problem because it happens in the context of a broader racial erasure and by the way he demanded and got 100 percent of the publishing for “Can I Kick It?” But I suspect we can agree that his gesture is a knowing commentary on the mechanics of pop songs. IT’S META MACHINE MUSIC. Oh shit I did not see that coming. Anyway, VU knows how it works. And we listen with the pleasure of that knowingness, if that is something in which we can take pleasure. They know what happens next.

Jonathan does not know, much less know better. I am not claiming he is somehow ignorant. I am not claiming he is a holy fool, that he is free of influence. It’s the stance he takes toward the world, toward what I am calling history. He’s the farthest thing from a Besserwisser we could imagine. No matter how many VU concerts he has seen, he does not know what happens next in his own song, and neither do we, and the song is that not knowing, that capacity to be amazed and spellbound by what you see as you come over the hill even if you have driven this road a thousand times, the exact opposite of a VU song, and that makes the song unbelievably thrilling despite its extraordinary restraint. I just don’t know what to do with people who hear in the downtown art drone of VU and in the repetitions of “Roadrunner” the same thing, whatever the fucking chords are.

But to insist on Jonathan’s lack of knowing is finally in tension with your claim that he does know the terrible thing, a claim with which I agree! So I contradict myself and here we need a sidebar of a zillion words to deal with kinds of knowing. But the terrible thing he knows is, there’s no right move from the starting position named “teenager.” No amount of knowing dissolves the essential problem. For this holy moment you have no particular place to go. But you will, and soon. You’re gonna have to pay off your own car before too long. Whether you go to work in the shoe factories that for a long time dominated Natick, or go to work in the Factory like Lou Reed, it’s still the factory. Jonathan is just driving around looking for a way out. That’s it, that’s the book.

Joshua

Joshua Clover is the author of seven books, a former journalist, a professor of English and Comparative Literature at University of California Davis, and a communist.

Alex Abramovich is the author of several books (most notably, Bullies: A Friendship) and the coauthor of several others (most recently, Courtney Love’s forthcoming memoir, The Girl With the Most Cake).

Copyright

© The Paris Review