Re-Covered: A Sultry Month by Alethea Hayter

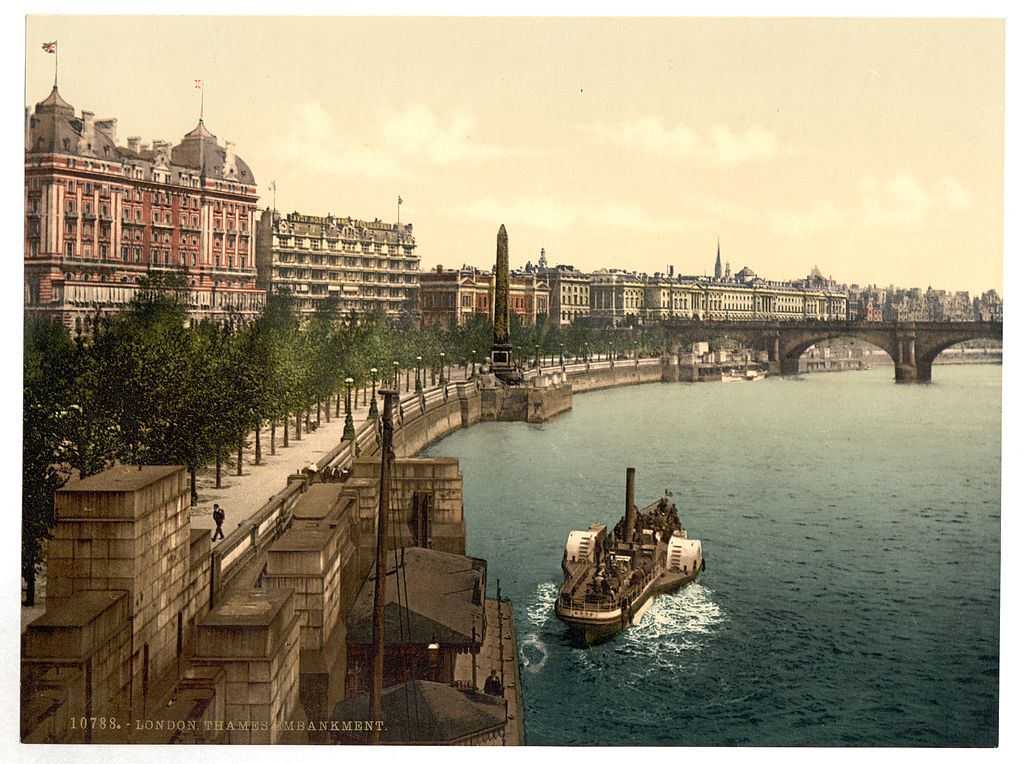

Thames embankment, London, England. Photochrom Print Collection, public domain, via Wikimedia Commons.

One hundred and seventy-six years ago today, on the evening of Monday, June 22, 1846, the painter Benjamin Robert Haydon—sixty years old and facing imminent financial ruin—locked himself in his studio in his house on Burwood Place, just off London’s Edgware Road. The month had been the hottest anyone could remember: that day, thermometers in the city stood at ninety degrees in the shade. Despite the heat, that morning Haydon had walked to a gunmaker’s on nearby Oxford Street and purchased a pistol. He spent the rest of the day at home, composing letters and writing a comprehensive, nineteen-clause will.

That evening, only a few streets away in Marylebone, Elizabeth Barrett penned a letter to her fiancé, Robert Browning. The poets’ courtship was still a secret, but they wrote each other constantly, sometimes twice a day. Like everyone else, Elizabeth was exhausted by the weather; earlier in the month she had complained to Browning that she could do nothing but lie on her sofa, drink lemonade, and read Monte Cristo. “Are we going to have a storm tonight?” she now wrote eagerly. And, indeed, as dusk turned to darkness, the rumbles of a summer tempest began. By ten o’clock, Londoners could see flashes of lightning on the horizon.

Back in Burwood Place, meanwhile, passing her husband’s studio on her way upstairs to dress, Mrs. Mary Haydon tried the door, but found it bolted. “Who’s there?” her husband cried out. “It is only me,” she replied, before continuing on her way. A few minutes later, Haydon emerged from his studio and followed her upstairs. He repeated a message he wanted her to deliver to a friend of theirs across the river in Brixton and stayed a moment or two longer, then kissed her before heading back downstairs. Once again alone in his studio, he wrote one final page that began, “Last Thoughts of B. R. Haydon. ½ past 10.” Fifteen minutes later, he stood up, took the pistol he had bought that morning, and, standing in front of the large canvas of an unfinished current work in progress, “Alfred and the First British Jury”—one of the grand historical scenes he favored but brought him few admirers—shot himself in the head.

His wife heard the noise but paid it no attention; she and her daughter Mary assumed the troops they’d seen exercising earlier in nearby Hyde Park were shooting their weapons. Meanwhile, in the room below them, Haydon was fumbling to reload the pistol—the bullet had reverberated off his skull rather than killing him outright. Injured as he was, he dropped the gun before he was able to discharge it a second time. Groping around in desperation, he grabbed a razor and slashed twice at his throat, before sinking to the floor, the grim deed finally done. Oblivious to the gory scene on the other side of the studio door she passed on her way downstairs, Mrs Haydon set off for Brixton about eleven o’clock. When, an hour and a half later, Mary finally entered the studio, she found her father’s dead body lying in a pool of blood that she first mistook to be red paint.

Outside, a torrential downpour assailed the London streets—one woman slipped on the wet pavement, breaking her leg so badly surgeons had to amputate, while another suffered a fractured skull when a chimney pot came crashing down on her. The unbearable heat had finally broken.

***

The sad events of this portentous night are the fulcrum of the British author Alethea Hayter’s compelling group biography, A Sultry Month, first published in 1965. The book opens four days earlier, on Thursday, June 18, 1846, with the arrival, at Barrett’s home at Fifty Wimpole Street, of five pictures and three trunks, sent by Haydon to his friend by correspondence for safekeeping. As had happened on seven previous occasions in the past twenty-five years, Haydon feared he was about to be arrested for debt and his possessions about to be seized, so he was attempting to remove them from harm’s way. The book draws to a close on Monday, July 13, the day Haydon was buried in Paddington New Churchyard. A tragic and rather pitiful figure during his lifetime—“All his life he had utterly mistaken his vocation,” wrote Dickens of Haydon, “he most unquestionably was a very bad painter”—the course of history has done little to change this. Yet in Hayter’s clever and cunning hands, the story of his life’s end, and the cast of characters caught up in it, whether through friendship or happenstance, makes for unexpectedly gripping reading.

Then there’s Barrett and Browning. She’s still living at home with her domineering father, but the lovers are busy plotting their elopement, which will take place at the end of the summer. Meanwhile, in Chelsea, the Scottish essayist and historian Thomas Carlyle and his wife, Jane, are experiencing a period of marital strife, though they try their best to present a united front when they host the wealthy German novelist Ida Gräfin von Hahn-Hahn: “(Countess Cock-cock! What a name!) She is a sort of German George Sand without the genius,” writes Jane in a letter to her cousin. The author of the popular semiautobiographical novel, The Countess Faustina (1841), about the romantic escapades of a sexually adventurous countess traveling through Asia, Hahn-Hahn was the toast of London literati. And while everyone’s rather disappointed to discover that she’s no great beauty, with false teeth and only one eye, they’re downright shocked when they realize her gentleman escort is actually her lover. Hayter’s protagonists might be liberal-minded for their era, but they’re still Victorians! A further list of supporting players includes the banker and poet Samuel Rogers and the Irish art historian Mrs. Jameson, a close friend and confidant of Barrett’s—not to mention Dickens, Keats, Wordsworth, and Tennyson, who make cameo appearances.

In the houses of Parliament, meanwhile, the government is embroiled in heated discussions about the Corn Laws. These were high tariffs on imported grain that were supposedly meant to encourage domestic production of corn, but actually just kept the prices exorbitantly high. This benefited already wealthy landowners but was increasingly ruinous for both the working classes, who struggled to afford to eat, and for merchants and manufacturers, who lost business because their patrons were forced to spend such a huge portion of their income on grain. The failed harvests across the UK and the potato famine in Ireland forced the prime minister, Robert Peel, to bend to the increasingly loud call from the British population, and on Thursday, June 25, the Corn Laws were repealed. This resulted in a backlash from the landowners of Peel’s Conservative government, and a week later he was forced to resign from office due to lack of support in the party.

Hayter’s London is a hotbed of political and personal crises, captured at a moment of great transition: Hampstead, for example, is still a village reached by walking through open fields—Haydon makes the journey himself only the day before he dies—as yet to be swallowed by the metropolis as it belches outwards. But with the construction of the new Birmingham railway line from Euston, along which the “tentacles” of Camden Town stretch out into the fields, this growth is beginning.

And permeating the book is the heat, the atmosphere of fervor and foment that only heightens as the mercury climbs up the barometers. “Oh—it is so hot,” Elizabeth Barrett writes to Browning early in the month. “There is a thick mist lacquered over with light—it is cauldron-heat, rather than fire-heat.” This wasn’t languid summer sun; these were temperatures that were “murderous.” Wherrymen died of sunstroke, farm laborers perished from heatstroke, numerous people drowned while bathing; there was cholera in the cities of Hull and Leeds and typhus outbreaks in London; grass singed and scorched in the fields, fires broke out in houses across the city, and the stink from the sewers rose in a heavy miasma. It’s both visceral and metaphorical: Haydon’s spiralling descent into despair, Barrett and Browning’s increasingly passionate correspondence, even the Carlyles’ hot and bothered bickering; they’re all infused with a sense of fevered, infernal frenzy.

***

A Sultry Month possesses many of the ingredients of a great novel—from the urgency of its pace and plot, to the intimate understanding of and access to its protagonists—but it’s actually a painstakingly researched and meticulously constructed act of literary collage. Most significantly, nothing in these pages has been invented. “Every incident, every sentence of dialogue, every gesture, the food, the flowers, the furniture, all are taken from the contemporary letters, diaries and reminiscences of the men and women concerned,” Hayter confirms in her foreword. She had no need to invent anything because all the material was already there for the taking—“nearly all” of her subjects were “professional writers with formidable memories and highly trained descriptive skills.” All she had to do was choose what was interesting or relevant, and then organize it into a single, cohesive, chronological narrative.

In “A House of One’s Own,” her brilliant essay on the perennial allure of that most famous of all London-based literary and artistic circles, the Bloomsbury Group, Janet Malcolm declares that the collective’s most canny achievement “was that they placed in posterity’s hands the documents necessary to engage posterity’s feeble attention.” It’s these—letters, memoirs, and journals—and only these, she continues, “that reveal inner life and compel the sort of helpless empathy that fiction compels.” These artifacts inspire a particular fascination—and often inspire the biographer. But this initial “rapture of firsthand encounters with another’s lived experience” is, as Malcolm laments, rarely present in the resultant biography, which usually “functions as a kind of processing plant where experience is converted into information the way fresh produce is converted into canned vegetables.” Hayter was no stranger to the traditional biographer’s method; in 1962 she published the acclaimed Mrs. Browning: A Poet’s Work and Its Setting. But, circling around the same subject in the years that followed, and having assembled a rich cache of material of the kind whose magnetism Malcolm exhorts—those “letters, diaries and reminiscences” that Hayter references above—she took an inspired and radically different approach. When it came to writing A Sultry Month, she let this original material speak for itself, and thus managed to deliver exactly the “rapture” of those encounters with “another’s lived experience” of which Malcolm speaks.

Although then “a form which is so new as to lack a name,” as Anthony Burgess put it when he hailed A Sultry Month as a “masterpiece,” this kind of biography of a microcosm—a personal history that is tethered to a specific place, moment or other organizing factor—is ubiquitous today. (We need only think of Phyllis Rose’s Parallel Lives: Five Victorian Marriages (1983), which, incidentally, revisits the Carlyles’ union; Jenny Uglow’s The Lunar Men: Five Friends Whose Curiosity Changed the World (2002); and most recently, Francesca Wade’s Square Haunting: Five Writers in London Between the Wars (2020), to name just a few of the best examples that have appeared in the years since A Sultry Month’s publication.) Hayter’s precision, concision, and sharp narrative thrust still distinguish the book today, but it’s hard to comprehend just how groundbreaking A Sultry Month felt to readers in the mid-’60s. Its publication marked the dawn of a whole new kind of life writing.

Though Hayter’s subjects were historical, in order to tell their stories, she drew inspiration from one of the most cutting-edge artistic techniques of her day. “My object—like that of the Pop Artist who combines scraps of Christmas cards, of cinema posters and of the Union Jack to make a picture—has been to create a pattern from a group of familiar objects,” she explains. In the same way that pop artists like Robert Rauschenberg or Jasper Johns constructed their work by repurposing and repositioning images—or parts of images—created by others, Hayter wrote by recycling material that would be already “familiar to any student of the period.” The originality of her project lies in the composition: she desired “to show a set of authors—all of whom have had their separate portraits painted many times at full length—as a conversation piece of equals, existing in relationship to each other at a particular moment, encapsulated with one dramatic event in an overheated political and physical climate.”

Hayter apparently loved gossip, a proclivity that served A Sultry Month well. Poking around in the letters and private papers of her subjects gave her “the sensation of being an inquisitive housemaid.” Reading the finished book gives the delicious impression of listening at doors or catching snatches of conversation on the stairs—an effect of the close attention Hayter pays to the full range of trifles and trivialities that constitute her subjects’ lives. Jane Carlyle, we learn, never quite forgave Browning for clumsily burning a hole in her carpet with a hot teakettle; Barrett walks her beloved golden cocker spaniel, Flush, along Wimpole Street in the relative cool of the evening, her eyes peeled for dog stealers; the Carlyles are tormented by constipation because they refuse to eat any fresh fruit or vegetables. By means of such inclusions, Hayter reminds us that the marrow of life is found in its minutiae, and in her alchemical hands, dusty historical figures are transformed into once-living and breathing beings with the same foibles and fears as the rest of us.

Lucy Scholes is senior editor at McNally Editions.

Copyright

© The Paris Review