Parables and Diaries

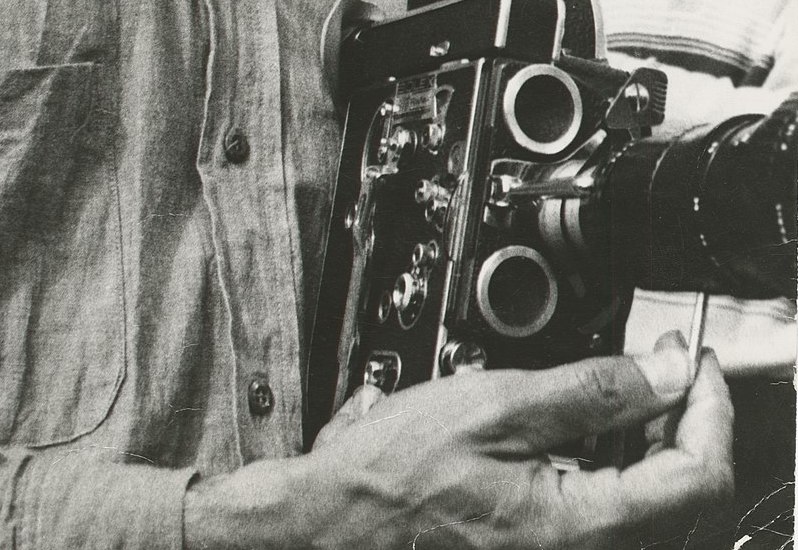

Viktoras Kapočius, Jonas Mekas visiting Biržai, Lithuania, 1971, licensed under CC BY 4.0.

On a recent hungover Sunday, I agreed to meet an old college friend uptown at the Jewish Museum to see their installation “Jonas Mekas: The Camera Was Always Running.” Trying not to betray my impairment, I sat down with relief in the black-box room, ready for the cameras to roll. After all, the movies have always been a refuge for the weary—for when you’d still like to feel something but you can barely move.

Across a rough semicircle of twelve screens, Mekas’s intimate, nearly five-hour epic of his personal life, As I Was Moving Ahead Occasionally I Saw Brief Glimpses of Beauty, flooded the darkness. Each screen was devoted to a different segment of the film, creating an anarchic jumble of sound and image: Central Park picnics, Cape Cod swimming, a cabin in the green woods, flowers in the breeze, the waves of the sea, grass, Mekas playing the accordion, wine and dinners, the city in the snow. Letting it all wash over me, I felt moved, and restored to the fullness of experience.

In the film, Mekas, who passed away in 2019, says he is uncertain as to where his life begins or ends—his solution was simply to record everything—and the museum’s unconventional screening accents this uncertainty. Something, of course, is lost when a life’s work passes you by in a few brief minutes: Isn’t the ability to concentrate on a single captured moment a luxury now, and one that is increasingly rare? Still, somehow the loss seemed appropriate to Mekas: his canvases grew so immense exactly because they strove so tirelessly to preserve the fleeting. It made me want to return, knowing that there was still more to see.

Mekas’s openness to experience made him the linchpin of a new film culture (the name of the magazine he founded) in New York, and institutions like the Anthology Film Archives—one of the city’s greatest, and most uncompromising, theaters—exist because of his community-building: his movies are populated by everyone from Stan Brakhage to Andy Warhol and the Velvet Underground. In A Letter from Greenpoint, the film that screened next, Mekas chronicles the twilight of that more affordable, bohemian New York: the loft where Mekas has lived for decades is vacated, its last light extinguished. But Mekas soldiers on in Brooklyn, getting drunk, singing along raucously to Bob Dylan with a younger friend, and recording it all. (An extensive selection of Mekas’s work can be found on his personal website.)

After a couple hours of the show, my friend and I went out into the park. I would have liked to stay longer, but time with friends who are only visiting is limited, and cinema has to give way to life again: what the black box has concentrated is diffused back out; glimpses return to the stream of time. It was an unusually hot day for early March, the kind everyone knows is becoming less unusual all the time. I looked at the clouds, the reflections on the surface of the reservoir, parents walking with their children, the new grass. All of it could become part of my own record: I just had to notice it first, and then try to keep it.

—David Schurman Wallace

The past few weeks of my life entailed a lot of driving. On the road, whenever I wasn’t listening to the news from Ukraine, I was playing the audiobook of The Parable of the Sower by Octavia E. Butler, read brilliantly by Lynne Thigpen. (I’m one of those who believes listening to an audiobook qualifies as reading.) The novel, written in 1993, is scarily prescient; it paints a picture of an apocalyptic near-future America that has been torn apart by climate change and rampant privatization. The plot is violent and bleak, yet driven forward by the grace and pragmatism of the book’s narrator, a teenage girl named Lauren.

Listening to Parable these days has felt less like an escape from the terrible news than a retelling of it, refracted back to my ears through the prism of space-time. When “real life / feels like science fiction // and science fiction can be truer than life” (per “Garden of the Gods,” Ama Codjoe’s dazzling poem about Butler), I find myself taking a perverse comfort in stories that don’t flinch from the scale of human destructiveness, and especially in those that imagine new means of surviving it. That’s an awful lot to ask of art, I know. But lately, trundling alone around the Northeast in my rusty little car, I feel dissatisfied with anything less.

—Maggie Millner, author of “from Couplets“

What can poetry do? In low moments, I often wonder this, and almost begin to understand the impulse towards art for art’s sake. But writers like Solmaz Sharif—whose latest collection, Customs, came out last week—provide a reminder that language is duplicitous: it can subvert as much as it betrays. “I said what I meant, / but I said it / in velvet,” she writes towards the end of “Patronage”:

I said it in feathers.

And so one poet reminded me,

Remember what you are to them.

Poodle, I said.

And remember what they are to you.

*

Meat.

Customs, like her first collection, Look, is a work that seeks to dismantle the hypocrisies of the English language: the way it is wielded by artists to prettify and by politicians to destroy. As Sharif writes in another poem, “Dear Aleph,” “You’re correct. Every nation hates / its children. This is a requirement of statehood.”

—Rhian Sasseen

Copyright

© The Paris Review