On Cary Grant, Darryl Pinckney, and Whit Stillman

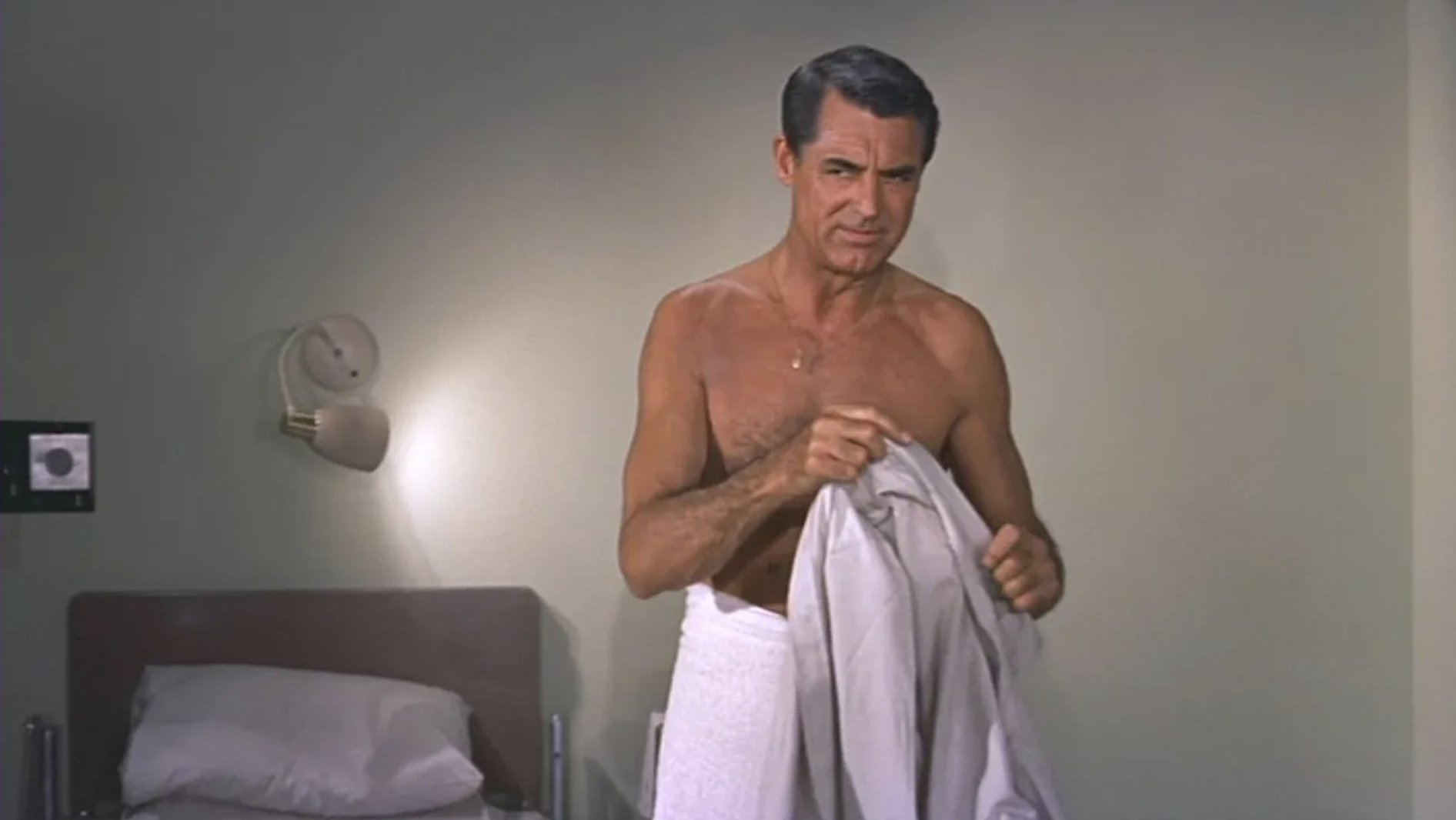

During the COVID confinement and afterward, I watched around sixty films starring Cary Grant. What a comfort to have him in my mind before I slept. No matter if he is comic or desperate, self-possessed or wounded, romantic or cool, he is ridiculously good-looking and seems never to know this. I love it when he puts his hands on his waist and pushes his hips forward as if about to dive or perform some acrobatic trick. His slim, athletic torso and long arms are always tanned. Sometimes he wears a fine shimmering gold medal around his neck. I love his dark eyes that have not forgotten his youthful suffering. He makes me laugh when he rolls his eyes around with his own special brand of sophisticated nonchalance. Though he isn’t aggressive, he doesn’t seem weak either. I find him buoyantly masculine. I can’t resist watching him. A few days ago, on a flight to Los Angeles, I watched Alfred Hitchcock’s hugely entertaining thriller North by Northwest again. Grant was fifty-five when he made this film and long past his box office peak in the screwball comedies that made him famous. In the Hitchcock film he wears a nice-fitting, light gray suit with a gray silk tie and cuff links. The suit gets dirty, sponged off and pressed, then dirty again. Grant’s hair is a little gray, too. I don’t wear ties anymore, but I would wear a tie worn by Cary Grant. North by Northwest appeared in 1959, around the time that he was experimenting with medical LSD and searching for more “peace of mind,” as he called it. I don’t really know what a great actor is, but I think Grant is sensational.

—Henri Cole

Read Henri Cole’s recent essay on James Merrill here.

In a scene midway through Whit Stillman’s Barcelona, which I rewatched this week, the Spanish Marta (played by a not-so-Spanish Mira Sorvino) is explaining to patriotic American naval officer Fred why her friend Montserrat has left his also American cousin, Ted.

Ted’s romantic rival, she says—in close-up, in a possibly Catalan accent—has lectured Montserrat about the ills of American society:

And he painted a terrible picture of what it would be like for her to live the rest of her life in America, with all of its crime, consumerism, and vulgarity. All those loud, badly-dressed, fat people watching their eighty channels of television and visiting shopping malls. The plastic throw-everything-away society with its notorious violence and racism. And finally, the total lack of culture.

“It’s a problem,” agrees Fred.

—Rebecca Panovka

Read Rebecca Panovka’s culture diary, which chronicles a week of June in New York, here.

I usually start my summer by reading Sleepless Nights, mostly because of the opening sentences: “It is June. This is what I have decided to do with my life just now.” My love for reading Elizabeth Hardwick is matched only by my love for reading about Elizabeth Hardwick, so it’s only fitting that I’m finishing the summer reading Come Back in September: A Literary Education on West Sixty-Seventh Street, Manhattan by Darryl Pinckney. The memoir, which will be released in October, is an impressionistic recollection of Pinckney’s early years as a writer in New York City, when he was fresh out of school and trying to learn who he wanted to be by studying Hardwick, his former professor, as well as Barbara Epstein, his new editor at The New York Review of Books. I especially liked Pinckney’s anecdotes: Hardwick bringing home a cardboard box of what would become Sleepless Nights but was then called “The Cost of Living”; dinners and joints with Hardwick’s daughter Harriet; and nights spent watching the B-52s perform. It’s a portrait of a special phase in many young lives, when our relationships with the people who have the greatest influence on us can feel both fated and random.

—Haley Mlotek

Read Haley Mlotek’s essay on the perils of the month of August here.

Copyright

© The Paris Review