Narcotics

I was at a sedate little cocktail party in SoHo, one of those uneventful parties I wound up at once a week. It was a typical SoHo art shindig: there was a full bar, sliced raw veggies and clam dip, bread sticks, mini-wieners and pea-size meatballs floating around in red sauce in a hot stainless-steel pan. The usual bunch of scrubbed, aspiring, New York art climbers were there mingling and tittering and chit-chatting discreetly, the women in sensible low heels and expensive stockings with no runs, and the men in silk ties, designer sports jackets, and clean jeans.

A few of the men with goofy-looking bloodshot eyes were passing around marijuana; the ladies were giggling and tossing their sleek pageboy hairdos around, acting like they’d never seen marijuana before. These women were young, fresh out of college, but they were always trying to make themselves look old for some reason. I never understood that. They wore gray baggy dresses and a few pieces of tiny, tasteful, conservative jewelry.

There was a man standing near me at the butlered bar, flirting with one of those bland-looking, corn-fed debs in gray. They were smoking a joint. The girl—this perky, peppy, preppie—started to cough, and he laughed and attempted to cuddle her for her cuteness. He turned to me only long enough to hand me the joint.

“Here,” he said, “you look like the type that could handle this.”

“No thanks,” I said, “I don’t use drugs … only narcotics.”

That was the truth. I’d stopped using marijuana. It made me paranoid.

The person I’d come with, Alvain Arles, the art critic and historian, came over to me.

“This is a real bore. A snore fest. Let’s get out of here,” he said. Alvain was many things, but never boring. He had a hard time tolerating people who were. I hurled back my martini and we slipped out the door.

“You think UFO or SHELL SHOCK will be out yet over on Fourth Street?” he asked.

“I don’t think so. But ROADRUNNER or SEVEN UP or NAUSEA ought to be out on Seventh Street,” I said, as we tried to hail a cab.

“How about T.N.T. or DOLT BOLT?” he said in the cab, counting his money, “they’re a little stronger.”

“Let’s just head straight for 10th Street for POISON or BLACK DEATH,” I said, “they’re always open. They have TOXIC and RADIOACTIVE there too.”

“So where’ll it be?” the cab driver asked.

“Just head for the east side,” Alvain said. “How about IMPALE or PEG-LEG? VIRGIN DEVIL, X- RATED? Or PARALYZE or WALLOP or LOT O’ROT?”

“Never had any of those except WALLOP. I don’t even know if WALLOP still exists. You have to go for the newest stuff … after a week or two the quality always plummets. How about SWEET SIXTEEN or TRUE BLUE? Wait, wait! Why not TOILET?”

“Hey!! Okay!! Yeah!! TOILET’s out now, so’s TORTURE!” He got excited. “Driver, take us to East Third Street and Avenue B,” he said, and settled back, happy. “TOILET and TORTURE. Either one is great.”

We were talking about heroin. These were the names rubber-stamped on the little glassine packages of ten-dollar amounts sold on the Lower East Side streets. Junkies, weekend users, and other heroin aficionados memorized all the names by heart; they knew where to get each one and exactly what time the “store” opened.

I wondered what this cab driver thought. Maybe he thought we were going over the names of our favorite exploitation films or dirty books, or discussing S&M bars.

We got to the corner of Third and B, and Alvain hopped out. “You hold the cab,” he said. “It’ll take one second.”

The cab driver waited for four seconds and then he turned to me, “Hey, I don’t wanna sit here. I’m losing fares,” he said.

“Don’t worry. We’ll make it worth your while,” I said.

“No. Pay up, I gotta go.”

I gave him the money and got out. That was a drag. Ordinarily, it was no calamity being without a cab, but I was looking a little too spiffy in my cocktail regalia for that neighborhood at that hour in that time of the decade. I was also holding the rest of Alvain’s money, and junkies can smell money, especially if they’re thieves or dope sick. I looked around for Alvain and saw him down the block talking to a Puerto Rican guy in red-and-white running clothes, probably flirting, because the guy was cute and he was Alvain’s type. I walked up to them and heard the Puerto Rican say, “Yeah, TORTURE’s smokin’ righ’ now. I seen ’em carron out somebody who jes O.D.ed on it. You give me ya money an’ I’ll git it fa ya.”

“And that’d be the last I’d see of you,” Alvain laughed. “No, I know where to go.”

The guy kept trying to think of some way to get some money from us, and he walked beside us talking nonstop. I could tell that Alvain was falling in love.

“Okay, I’m gonna give ya one of my bags,” Alvain said, and gently tweaked the Puerto Rican’s beardless chin.

We walked over to the burned-out building where people were lining up in the dark hallway, clutching their money, waiting to buy. Everyone was very quiet. The first guy in line put three ten-dollar bills through a slot in a door in the back of the hall and out of the slot came three glassine bags of TORTURE.

A big black guy standing at the hall entrance was keeping everything moving. He worked there. “Hurry up, move along, have your money ready, step up,” he was saying.

A punk rocker in front of me was talking to a skinny Italian American guy, “Yeah, somebody jes O.D.ed on this shit minutes ago. Must be the best shit on the street right now.”

“Told ya,” the Puerto Rican reminded us.

“Great!” another person in line said, “I’m lucky I came out now.”

“Yeah, my ol man was sa high on TORTURE yestada, he was throwin’ up all ova da place,” said a skinny birdy girl in a blue leather jacket. “Was goooood sheeet, man!”

“Shhh!” said the big guy at the entrance.

Mixed in with the losers and hardcore users were a few prosperous types waiting in line: a Wall Street man, a blonde-haired model I’d seen in last month’s Vogue, a famous post-minimalist sculptor, a famous filmmaker, and a guy I’d seen once on some daytime soap opera, Another World, or The Edge of Day, or City Hospital. I can never remember the names of those shows.

When Alvain and I got to the dope door, Alvain slipped his money through the slot and out came six little white rectangular packages, taped with clear tape and stamped with the word TORTURE. With the goods, we bustled out the building and walked fast off the block. Alvain gave one to the Puerto Rican, and the Puerto Rican disappeared. Alvain was temporarily heartbroken.

He got over it immediately when we saw a cop car cruising down the avenue. Instant paranoia. If they decided to stop us, we would go directly to jail for the night, even if we’d had just one measly bag between us.

I heard the lookouts, young kids who worked for the dope houses from the rooftops, start yelling, “Bajando! Bajando!” That was the Spanish alert. It meant the cops were coming. We saw people walking very fast out of the building we’d just come from. Another watcher from the corner yelled, “Don’t run! Calm down! Don’t run!” People on the street who were heading toward the building just turned in their tracks and walked fast the other way. In less than two minutes the street was empty. The whole thing was really organized. By the time the cop car appeared around the corner and cruised slowly in front of the building, everything was peaceful.

I’d seen a funny scene one day at a dope spot on Rivington Street. People were lined up against a waist-high wall, waiting to score. Suddenly the alert went out, a cop car was coming, so the seller and all the people in line dropped on all fours and were hidden by the wall. After the car went by, it was business as usual, everybody just stood up.

The sellers were always trying to be one step ahead of the cops. A few dope houses were doing the routine where the sellers would lower a basket from the window on a rope, the customer would put in his money, and the basket would be raised. Down would come the packages of dope. When the cops came, the basket would be raised quickly and the crowd would disperse. The dope scene had no room for sloppy salesmanship. There were many workers.

Before the cop car got to us, we found a cab right on the next block. That was luck. We drove past Ninth and B and there was a guy with a knife standing over a person who’d been in line at the building we’d just come from. The guy on the ground wasn’t hurt, he was reaching into his pants pockets, pulling out his heroin, and handing it over. As we whizzed past I heard him cursing, “Shit. Dammit, now I’m gonna be sick. Common, man, leave me jes one bag. Fuck!”

“Poor kid.” Alvain looked back at the scene.

“He ain’t gonna hurt ’im,” the cab driver said. “He’ll pralee leave him one bag too.” Anyone on the streets there at that hour knew what was happening.

“Good thing we found you when we did,” Alvain told the cabbie.

“Yeah. I saw you two in line,” he laughed. “Where to?”

Friends of mine who went to buy dope in that neighborhood would sometimes have their watches, earrings, rings, and all their drugs and money taken. An artist friend had gone there right from an opening and he’d been all dressed up in his leather jacket, his cowboy boots, his best wool tweed pants. The person who ripped him off at knife-point wasn’t satisfied with just the dope and his money. The thief also took the jacket, boots, sweater, tweed pants, and even my friend’s boxer shorts. Stark naked, he started running home, freezing. On his way he searched the garbage cans for something to wear and finally found a dirty pink sweater, so he put his legs in the sleeves and ran, hoping he didn’t see anyone he knew. At least his wang was covered.

I laughed uproariously when he told me this story. In retrospect he too admitted it was very funny, but at the time he’d been mortified.

Things like this were always happening there. Friends would occasionally get arrested and wind up in jail for the night, or they’d lose their rent money. I’d never known anyone to get stabbed, but I’d never known anyone stupid enough to refuse to give up their stuff to a thief with a knife. Some people, new to street copping, would give their money to guys they thought were dope-house runners. Of course these “runners” wouldn’t ever return. If you happened to find a real runner, he would come back with the dope, but he’d take one or two bags for the run. So it was expensive and sometimes dangerous over there. For that reason, a couple of friends started selling heroin from their homes.

Barbara did. She’d written a mammoth novel that weighed something like ten pounds. She lived with her paramour, Jane, who was a rock and roll musician. They were good friends of mine before they started selling dope, and while they were selling it I saw them every day. Way more pleasant than the street, there was always a fire burning in the fireplace, lots of books on the shelves and flowers in vases. The cats were curled up on the chairs, there was the smell of fresh coffee. It was a home.

A few close friends would visit Barbara and buy some heroin. She made some money, everyone was happy. A habit takes months, sometimes years of dabbling with the stuff before it creeps up on you. I think a lot of these people were shocked to find themselves dependent on heroin even though they weren’t shooting it but snorting. Some people are dumb enough to believe you can’t get a habit if you aren’t using a syringe. At a certain point, a lot of the people I knew were using heroin, and some of them had habits, but no one took it too seriously. Everyone would always joke about it and everything was playful … but … being dope sick wasn’t pleasant, or fun, or romantic. Baudelaire, Poe, Coleridge, and all those writers who flirted with opiates didn’t write much about the sick part.

A heroin habit isn’t a problem for the user until there’s no money. I remember one New Year’s Eve party, held at this chic French restaurant, where all the guests were high on heroin. Everyone’s pupils were pinpoints; everyone was in a vegetable state, and acting cool like cucumbers. All eyes were dry at the stroke of midnight, and there wasn’t a whole lot of laughter; there wasn’t much outward display of emotion, like there was at drinkers’ parties, but in their black little junky hearts everyone was feeling warm and loving, they just couldn’t show it.

Everyone was standing up and mingling and talking; if they’d sat down they probably would have nodded out. They were all really good friends, people who’d gotten to know each other from the Mudd Club days before, and it was great to see everybody, even through the dopey haze of dope. These heroin users, like drinkers everywhere, had used the New Year’s Eve excuse to get higher for this night, and everyone was as stoned as they could be. At one point, after midnight, I turned to a filmmaker friend of mine.

“Look around,” I said, “Do you realize that every single person here is high on heroin? It looks like a Zombie Jamboree.”

He scanned the group, “You’re right,” he said, and laughed. I told everyone, and everyone laughed about it. We all had a good time that night, even though a lot of people were dozing off on their feet, buoyed up by the crush of friends around them. Yeah, everyone had fun, even the people who missed most of it because they were in the bathroom throwing up, or snorting more heroin.

It wasn’t like those typical SoHo art parties, like the one where they had passed marijuana around, where the guests had never known scary 4 A.M. walks in the heroin neighborhood, where none of them ever was dope sick, or ever ran home wearing a dirty sweater on their butt, or ever went without food for three days because there wasn’t enough money for food and dope too. Those people, the dope innocent, who never found themselves suddenly in a lowdown compromising situation of need, seemed like adolescents to a junky. The non-users were a whole different set of people. They might have been smarter for never getting involved in dope, but it’s a fact that when junkies become ex-junkies, they’re somewhat the wiser, having seen hell.

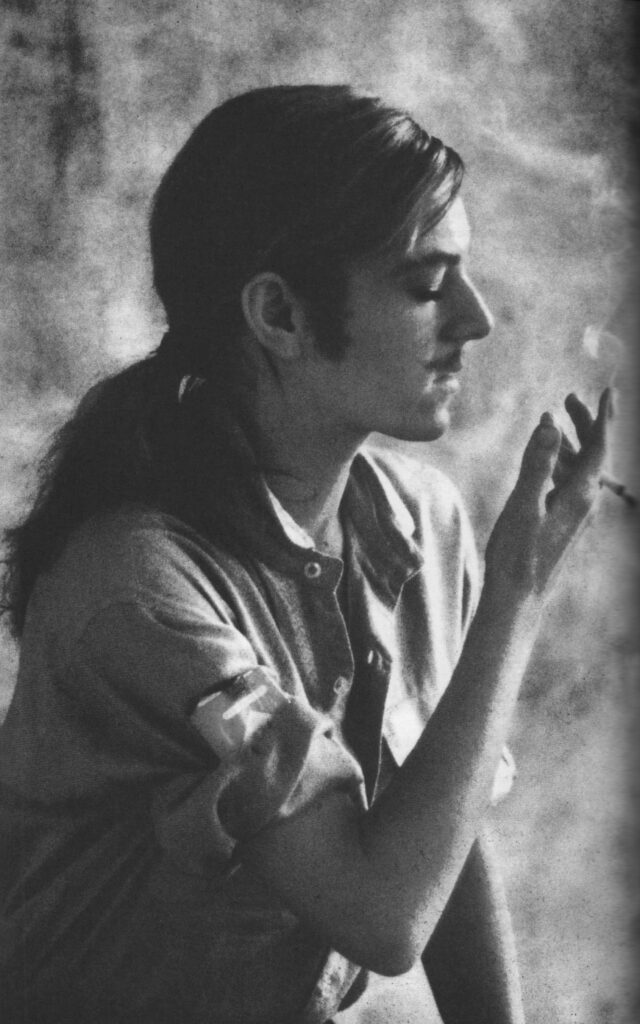

Cookie Mueller, née Dorothy Karen Mueller, played leading roles in John Waters’s Pink Flamingos, Female Trouble, Desperate Living, and Multiple Maniacs. She wrote for the East Village Eye and Details Magazine, performed in a series of plays by Gary Indiana, and wrote numerous stories that would only be published posthumously. She died in New York City of AIDS-related complications at age forty.

A version of this previously unpublished piece will appear in Walking Through Clear Water in a Pool Painted Black, New Edition: Collected Stories, which will be published in April by Semiotext(e).

Copyright

© The Paris Review