Modern-Day Lessons From Hiroshima

Editor’s note: The below article first appeared in David Corn’s newsletter, Our Land. The newsletter comes out twice a week (most of the time) and provides behind-the-scenes stories and articles about politics, media, and culture. Subscribing costs just $5 a month—but you can sign up for a free 30-day trial of Our Land here.

For four decades, I’ve had a recurring nightmare in which a nuclear blast occurs. The scenario is not always the same. Occasionally, the detonation is an escalation in an ongoing conventional war. More often, it’s a bolt out of the blue: I and others are on the street, and we spot incoming missiles and have but a moment to realize what is about to transpire before the warheads explode.

These dreams began, not surprisingly, when I was a reporter-editor in the 1980s for a now-defunct publication that covered arms control issues. After several years in the job, I found the task of constantly thinking about nuclear warfare psychologically burdensome and moved on—though I have dutifully maintained an interest in the subject. During my stint at that magazine, I met victims of the nuclear era, including downwinders (people suffering severe medical ailments due to exposure to radioactive contamination and nuclear fallout from nuclear tests) and survivors of the US nuclear attacks on Hiroshima and Nagasaki at the end of World War II. Their tales were haunting and cautionary, descriptions of the past and foretellings of a possible and awful future. Given all this, when I visited Japan as a tourist last month, I felt compelled to go to the first of the only two cities that have experienced nuclear devastation.

On the day I visited, it was full of life and people: families, tourists, young couples, street performers. It is a testament to resilience.Hiroshima is a wonderment. At 8:15 a.m. on August 6, 1945, on the orders of President Harry Truman, an American B-29 dropped a bomb that contained 141 pounds of uranium-235 over the center of the city. Hiroshima had been selected as a target by a committee comprising military officials and scientists from the Manhattan Project because it was an industrial center and home to a major military command—and its surrounding hills, according to the committee, would likely “produce a focusing effect which would considerably increase the blast damage.” The bomb detonated about 1,900 feet above ground. The blast leveled a 4.5-square-mile area and set off a firestorm that spread throughout the city. Tens of thousands of civilians were incinerated or injured that day. An estimated total of 140,000 Hiroshima residents were killed by the bombing or the ensuing radioactive fallout over the next few months. Many more died in succeeding years.

Today, 79 years later, Hiroshima, founded as a castle town in 1589, is a thriving city of 1 million people that boasts an active port and assorted industrial facilities and that is renowned for its delicious oysters. After the bombing, experts proclaimed that nothing would grow for at least 75 years in the wasteland created. Yet today the main avenue that leads to the blast site—Peace Boulevard—is lined with large leafy trees that were donated to Hiroshima from cities across Japan. And Peace Memorial Park, located where the bomb fell, is lush with flora. On the day I visited, it was full of life and people: families, tourists, young couples, street performers. It is a testament to resilience. What was once a hellscape is now a lovely spot where one can watch a Japanese troupe performing traditional Hawaiian dances alongside the Motoyasu River and eat takeout sushi beneath the iconic Atomic Bomb Dome, the only structure that was left standing in the blast zone. It was hard to reconcile the utter pleasantness of this Saturday morning with the horrific destruction that had occurred here merely a single lifetime ago.

Children playing beneath the Atomic Bomb Dome

The resurrection of Hiroshima—evidence that the greatest of calamities can be surmounted—is not the only lesson the city offers. The Peace Park is home to several memorials and a museum each designed to convey the message that the horrors of nuclear warfare must not be forgotten and, moreover, must be prevented by the worldwide elimination of nuclear weapons. At the Children’s Peace Monument, glass booths are full of thousands of colorful paper cranes—a symbol of peace—folded and sent in from kids around the globe.

The Children’s Peace Monument features booths with thousands of colorful paper cranes—a symbol of peace—folded and sent to Hiroshima by kids around the world.

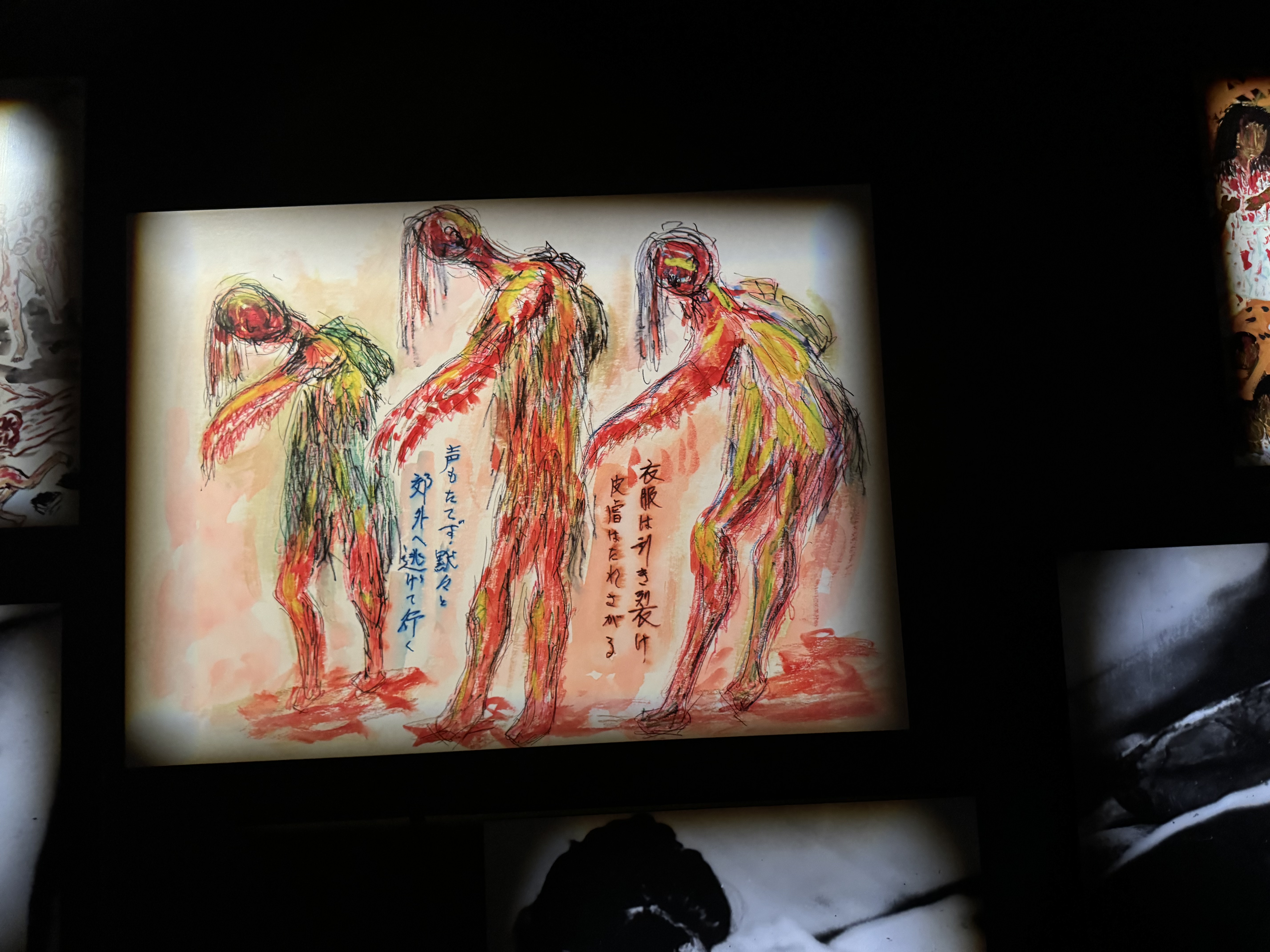

The years since the bombings, the people of Hiroshima and Nagasaki have not wallowed in victimhood. Instead, they have attempted to use their experiences to serve as peace advocates and messengers warning of the immense danger of nuclear weapons. The Hiroshima Peace Museum chronicles the nightmarish details of what occurred on August 6. It is full of harrowing descriptions of individual deaths. The museum displays the two known photographs from that day, showing survivors seeking assistance. More disturbing are the many drawings from people who lived through the blast. They depict scenes of a previously unfathomable human-made inferno showing, for example, civilians—men, women, and children—on fire. (There were many children in the center of Hiroshima that day, enlisted for work crews that were razing buildings to create fire breaks in case the Allies added Hiroshima to the list of cities targeted for their ongoing firebombing campaign.) Display cases contain artifacts of the blast: a melted Buddha, the charred uniform of a schoolchild, a kitchen clock stopped at 8:15.

One of the many drawings made by Hiroshima survivors on display at the Hiroshima Peace Museum

The museum presents the stories of scores of victims, including those later stricken by cancer and other diseases caused by radioactive poisoning. (Hiroshima has strived to identify all 140,000 victims, and these names are contained in a crypt in the park, close to the museum. Inscribed on this tomb: “Let all souls here rest in peace; for we shall not repeat the evil.”) It’s unsettling, as it should be, to confront such graphic accounts of carnage and pain. (As I noted last year, the blockbuster Oppenheimer film mistakenly opted not to include any scenes depicting the death and destruction caused by the bombing.) With its intent to share the full horror of the bombing, the museum is not for the faint of heart. But at the end of the exhibition, a visitor is guided to a room dedicated to efforts to reduce and eliminate the world’s nuclear arsenal. It describes the global lobbying work of Hiroshima and Nagasaki officials and residents who for decades have been pressing for nuclear disarmament. Their simple plea: Don’t forget and never again.

The tomb in Hiroshima’s Peace Park contains the names of the 140,000 victims of the atomic bombing.

A sidenote: Everyone gets to write their own history. One display in the museum explains that the United States decided to use the A-bomb because it believed that “ending the war with an atomic bombing would help prevent the Soviet Union from extending its sphere of influence” and that this would “also help the US government justify to the American people the tremendous cost of atomic bomb development.” These might have been factors in the decision, but this simple explanation leaves out Truman and his advisers’ desire to end World War II and avoid a massive and costly invasion of Japan, which was refusing to surrender unconditionally. I’ve long been sympathetic to the argument that the bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki were not justified, but it was bemusing to see how the custodians of Hiroshima contend with this question.

That exhibit highlighted the Franck Report, a document signed by a number of nuclear physicists who recommended in June 1945 that the United States not deploy the atomic bomb against Japan. It cited this passage:

We believe that these considerations make the use of nuclear bombs for an early, unannounced attack against Japan inadvisable. If the United States would be the first to release this new means of indiscriminate destruction upon mankind, she would sacrifice public support throughout the world, precipitate the race of armaments, and prejudice the possibility of reaching an international agreement on the future control of such weapons.

That was rather prescient.

It is moving and inspiring to see how Hiroshima has combined its remembrance of the atomic bombing with a passionate call for action to prevent any future use of nuclear weapons. And that means finding ways to avoid war. While absorbing the horrendous accounts in the museum, it was tough not to think about other bombings of civilian targets—past and present—that have caused tremendous casualties. (The American firebombing of Tokyo on a single night in March 1945 killed 100,000 civilians and left 1 million homeless.) This obviously includes Israel’s assault on Gaza following the October 7 attack from Hamas. The images we see of destruction in the Palestinian territory are not dissimilar to those of Hiroshima.

If the world cannot move beyond the use of war, the odds are that one day the devastation of Hiroshima and Nagasaki will be repeated—and probably on a much larger scale. In March, Russian leader Vladimir Putin, the architect of the brutal and criminal invasion of Ukraine, said that he was “ready” for nuclear war if American troops were deployed to Russia in that conflict. Earlier this year, the Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists noted that its Doomsday Clock—which characterizes the threat to the planet from nuclear weapons—is still set at 90 seconds to midnight.

The museum and the memorials in the Peace Park tell a blended story of human darkness and human hope. The United States caused terrible suffering and colossal damage—demonstrating what could become the fate of the world—and the victims responded by assuming the grand task of trying to protect others from such a catastrophe. A plaque in the museum describes the mission of Hiroshima:

On August 6, 1947, Hiroshima city delivers its first Peace Declaration. Ever since, the city has been telling the world about the reality of the A-bomb damage and calling for lasting world peace…Nuclear weapons and humankind cannot coexist indefinitely. Today more than ever, we must all embrace the A-bomb survivors’ desire to ensure that no one else will suffer their pain and sorrow. We must inherit their determination and pass it on to future generations.

My trip to Hiroshima felt like a pilgrimage. As I walked through the museum (packed with visitors, mainly Japanese) and strolled in the Peace Park, I wondered if this visit would trigger the return of that all-too-familiar nightmare. Yet there was something reassuring—and, yes, peaceful—in experiencing a collective witnessing of this catastrophe and in seeing the transformation of an apocalypse into a splendid site of community gathering. Hiroshima is certainly a reminder that we live in a world imperiled by nuclear arsenals and that we have yet to fully address that danger—and that human cruelty can be excessive and that the total annihilation of human civilization remains a possibility. But the city’s commemoration of the tragedy has a beautiful side. And so far, no nightmares.

David Corn’s American Psychosis: A Historical Investigation of How the Republican Party Went Crazy, a New York Times bestseller, is available in a new and expanded paperback edition.

Copyright

© Mother Jones