Making of a Poem: Farid Matuk on “Crease”

For our series Making of a Poem, we’re asking poets to dissect the poems they’ve published in our pages. Farid Matuk’s “Crease” appears in our new Winter issue, no. 246.

How did this poem start for you? Was it with an image, an idea, a phrase, or something else?

The images and ideas in the poem started long ago, in college, when I met a brilliant artist named Jeannie Simms. Around that time, they were doing a series of photograms, images made by laying an object on photographic paper and exposing it to light, called Interiors: Little Death. Jeannie had said their process was “to make love” to photographic paper. The results are gorgeous ruins, pieces of photographic paper bearing no image but deeply creased and distressed by Jeannie’s touch. I’ve never stopped thinking about the poetics of that process—the intersection of abstraction and embodied desire it involves, the way it confounds the photograph’s habit of delivering bodies as spectacle. Now, almost twenty years later, I’m mostly interested in Jeannie’s desire to create a space where sex, ritual, and art are one and to make a trace there. “Crease” is part of a longer manuscript, and a lot of that book tries to attend to moments where we can sense that entanglement as ethical, sensuous, and joyful.

The part of the poem about the falling flowers comes from time I spent as a visiting professor at University of California, Berkeley. The school puts you up in a little house donated by the poet Josephine Miles in an area just north of the campus that houses many seminaries and churches. In March of 2020, the neighborhood fell into a routine of evening walks. It was good to be outside and to have a reason to walk slowly, to know most folks around you were caring for their own health and for yours too. But there was also an air of privileged piety about the whole scene—very different than the lives of the “essential workers.” Hence the surliness in the poem about everyone wanting their “stupid church high on a hill.”

On my walks, I kept noticing floppy flowers dropped on the sidewalk. I liked the idea that they were so heavy with their own sex that they had to fall off their stems. The flowers still looked utterly vital sitting on the sidewalk. I am in desperate need of anything heavy enough to crease the infinite regress of what’s given to us as Cartesian space, anything that will make the void fold back so that there’s no void. That’s where my drafts started to test variations on the somewhat familiar phrase “not with but of.”

The last lines of the poem started when I was a very young child, falling asleep. When I’d close my eyes, I’d see faces above me morphing into one another. This still happens once in a while. The faces are sometimes ones I’ve never seen, but they appear in precise detail, and they’ll morph into faces of people I know who’ve affected me intimately. In this way the poem has a kind of argument or proposition—that dropping piety and committing fiercely to care and desire can open us up to being both the photographic paper and the touch, the consciousness drifting into sleep and the visitation, the sentence and everything that leaves it.

Was there anything particularly difficult for you in this poem?

That near rhyme of love and of was tricky for me. I’d avoided rhyme in my work in the past because of familiar critiques that it’s merely decorative, that it can lend a hollow authority, that it can tempt the poet into self-aggrandizing postures. I care about different kinds of truth in poems, affective, spiritual, ethical, documentary, narrative truths. But the notion that the language best suited to truth would be spare and blunt sounds a lot like how a police state would want a body to report for surveillance—naked and urgent. So I let myself be guided by James Baldwin and Audre Lorde. Baldwin called it sensuality, and Lorde called it the erotic, but both were interested in claiming the aesthetic, like rhyme, not as decoration or as a hierarchy of taste but as what Fred Moten would call an alternative to the anesthetic. So this poem is one of various explorations in the book of ways that rhyme can expand into its potential to enliven.

How did writing the first draft feel to you?

For a long time, pieces of this poem were lost, embedded in other poems or floating as fragments in a section of the manuscript I call “remainders.” I never delete. I cut text as needed to advance a draft of a poem, but I move that excised text over to this remainders section in case I need it later. When this poem finally came together, it did so easily, and that was terrifying, because it meant that I was nearing the end of my manuscript. It meant that I had studied the sections of the manuscript closely enough to notice the redundancies, the pacing of moods and images. I had whole stanzas and passages floating around in my head—the “problem” ones that hadn’t quite found a home yet, the ones that were doing too much where they were, the ones that might be speaking with each other if only I’d bring them together under a single title.

How many drafts were there, and what were the primary differences between them?

I’m not sure how many drafts this poem needed. I worked on it within a large manuscript file, which I would print out in full and revise by hand, then enter those changes into the digital file and rename it with a new date. The process started in earnest in 2019. In 2023 the whole manuscript experienced revisions consequential enough that I saved new date-stamped versions twenty-eight times.

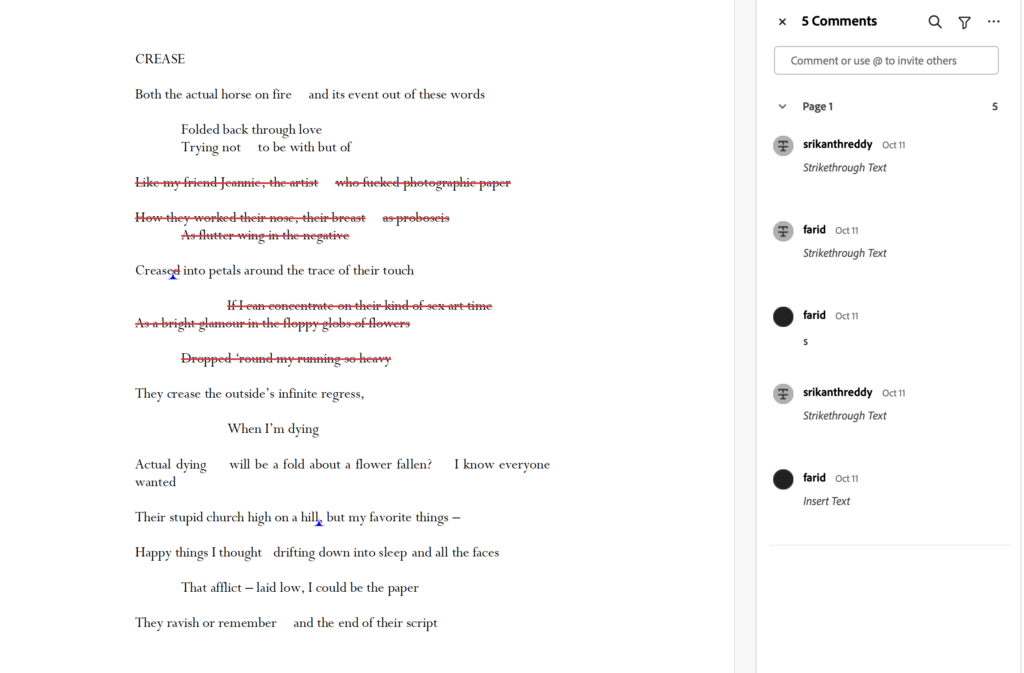

In the published version, Jeannie’s name is missing, as well as some lines that figured the artist’s gestures as the light touch of a butterfly’s proboscis and wing flutter—I was trying to get to the idea of the flowers. The question at the center of the poem also stretched across more lines in the submitted version. The Review’s editorial team suggested some cuts that I incorporated, though I customized their suggestions to maintain a causal logic between the poem’s opening lines and its central question.

Do you regret any of these revisions?

No. The suggested cuts helped me to see more clearly what was essential—why refigure the artist’s touch as a butterfly’s wing when the poem is most curious about the trace or crease? Nor do I regret that the version of the poem that’s in the final book manuscript has Jeannie and the photograms in it once again, though this time at a scope that fits into the poem’s overall composition without, I think, dominating or distracting. Sometimes the context of the book as a whole, particularly one with so many interconnected points of resonance, allows a poem to carry slightly more than it might in its isolated form in a magazine.

Farid Matuk is the author of This Isa Nice Neighborhood and The Real Horse.

Copyright

© The Paris Review