Flip It: A Tribute to bell hooks

bell hooks died last month of kidney failure at age sixty-nine; she was, according to her niece, surrounded by her loved ones when she passed. Small towns in Kentucky were the bookends of hooks’s life: She was born and raised in Hopkinsville, and departed this plane seventy miles east, in Berea, home of Berea College, where she’d taught since 2004 as a Distinguished Professor in Residence in Appalachian Studies, and where she had founded a research center, the bell hooks Institute, in 2014. In a chapter called “Kentucky is My Fate,” from her 2008 book Belonging: A Culture of Place, hooks writes:

If one has chosen to live mindfully, then choosing a place to die is as vital as choosing a place to live. Choosing to return to the land and landscape of my childhood, the world of my Kentucky upbringing, I am comforted by the knowledge that I could die here. This is how I imagine “the end”: I close my eyes and see hands holding a Chinese red lacquer bowl, walking to the top of the Kentucky hill I call my own, scattering my remains as though they are seeds and not ash, a burnt offering on solid ground vulnerable to the wind and rain—all that is left of my body gone, my being shifted, passed away, moving forward on and into eternity. I imagine this farewell scene and it solaces me; Kentucky hills were where my life began.

It occurs to me that Kentucky played an important part in hooks’s literary criticism as well. In a chapter of her 1995 book Killing Rage: Ending Racism, she identifies Toni Morrison’s 1987 masterpiece, Beloved, as among the most vivid representations in Black literature of the terrors of whiteness. The novel—set between 1856 and 1873 and based on the real-life story of an enslaved woman, Margaret Garner, who fled Kentucky for Ohio and murdered her baby daughter to keep her out of slavery—concerns a family who have escaped a Kentucky plantation known as Sweet Home. In Killing Rage, hooks (who had written her dissertation on Morrison’s first two novels), emphasizes the critical acuity of the character Baby Suggs, a Kentucky-born leader whom she calls “a black prophet.” A formerly enslaved woman, Baby Suggs preaches to Cincinnati’s Black population in a clearing, where they can enjoy each other’s company and be spiritually edified away from the surveillance of prying white eyes. Baby Suggs teaches her community about the importance of loving themselves. “Here in this here place, we flesh; flesh that weeps, laughs; flesh that dances on bare feet in grass. Love it. Love it hard … Love your hands! Love them … hear me now, love your heart. For this is the prize.”

Baby Suggs’s life is far more gruesome than bell hooks’s was, but these Kentucky-born women (one fictional, one real) share a taste and a respect for beauty, for the sensual and spiritual pleasures to be found in nature and in ordinary objects. On her deathbed, Suggs “used the little energy left her for pondering color,” lavender and pink, little snatches of vitality hiding in quotidian swaths of fabric and household bric-a-brac. When hooks envisaged that red lacquer bowl in “Kentucky Is My Fate,” I imagine she may also have been picturing lavender and pink, and the spectrum of verdant hues ascribed to Kentucky bluegrass. Like Baby Suggs, and with similar brio, hooks devoted herself to helping others better perceive and appreciate what oppressive cultures try to devalue, whether that’s the grace of chestnut-colored hands or the understated resonance of a scene in an otherwise throwaway film. In her 1994 book Teaching to Transgress: Education as the Practice of Freedom, hooks writes that “learning is a place where paradise can be created.” In her own way, hooks taught, as Suggs does, the critical transgressive potential of love and self-love, especially for and among Black people. Her clearing sometimes looked like a lecture hall, sometimes a small classroom. More often than not, her clearing was the pages of her books.

Reading hooks transformed my thinking on a bevy of subjects, including feminism, Buddhism, Christianity, celebrity, sex, romance, and the limits and possibilities of representation. In her 2003 book We Real Cool: Black Men and Masculinity, she notes that “throughout our history in this nation African-Americans have had to search for images of our ancestors.” This is true of my own search for biological forebears, but in terms of intellectual heritage, I feel lucky that I didn’t have to search very far to find the images hooks conjured in words, or the actual photographs of her on dust jackets. She was incredibly prolific, and her books were everywhere when I was coming of age. Since my teens, I’ve enjoyed the slow burn of revelation that comes through encountering and reencountering her work. I’ve learned the importance of being patient enough to let meaning reach me when I’m ready for it, allowing an insight to land slowly and settle in my mind. Rereading hooks has helped me to revel in ideas without necessarily articulating them to anyone but myself, lest I interrupt the process of recognition by blabbing what I think I know too soon. As the old folks say, some things can remain private, and these reading experiences that overwrite each other and take years to develop are among the most pleasurable.

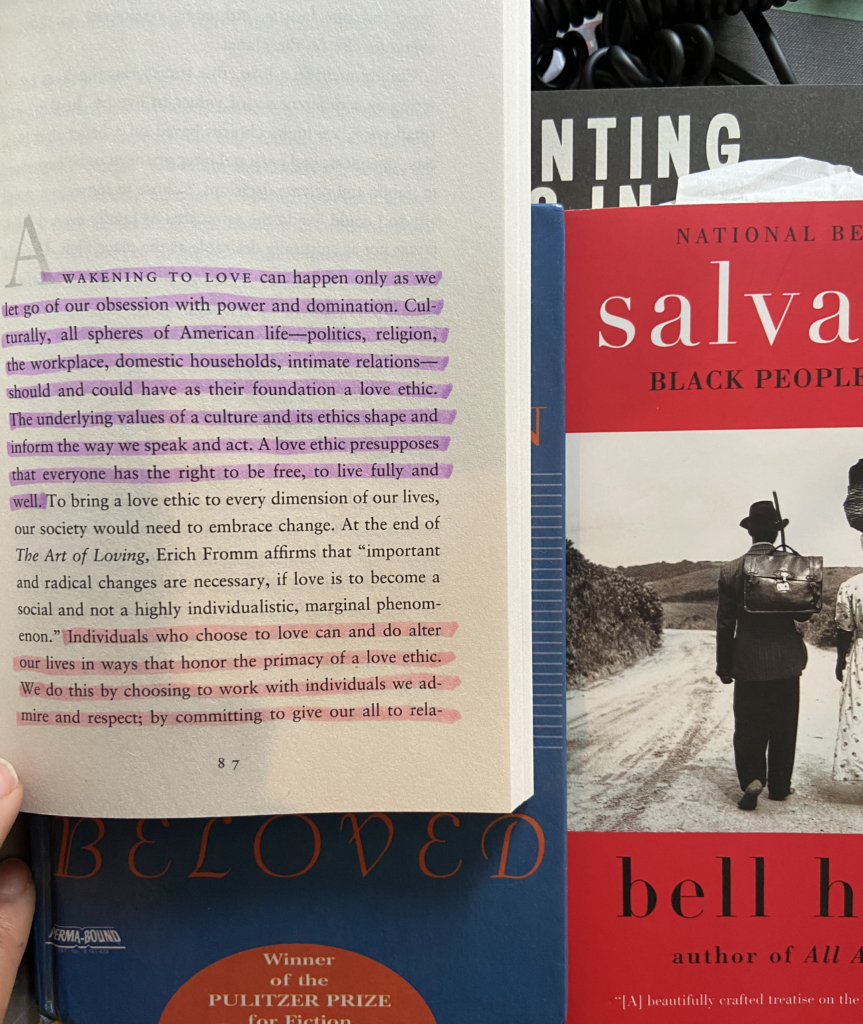

In other words, hooks’s writing allowed me to access all the tender feelings that come as a result of knowing oneself. In Sisters of the Yam: Black Women and Self-Recovery (1994), hooks describes how the notion of “erotic metaphysics” can be applied to enable Black women to “know and love who we are so that we can become more fully ourselves in the space of passion and pleasure.” That’s an experience I recognize—the eroticism of thought, the arousing sensation of concepts coming together. Ideas, I’ve discovered, are nimble like bodies and can be flipped over, just as the writhing women in Chantal Akerman’s 1974 film Je Tu Il Elle (I, You, He, She) tumble across a bed as a means of foreplay. I disagreed with some of hooks’s ideas, and was ambivalent about a few of her recommendations, but I always enjoyed wrestling with their meaning. Books like All About Love: New Visions (2000) and Salvation: Black People and Love (2001), shifted my perception, suggesting that love could be a revolutionary ideal and a mode of intellectual engagement. Love unfolds in private, of course, but I learned that it could also be practiced on a larger scale by treating the world as an object of desire. As hooks writes in All About Love, “To begin by always thinking of love as an action rather than a feeling is one way in which anyone using the word in this manner automatically assumes accountability and responsibility.”

In the fall of 2007, when I started my first year as an undergraduate at Temple University, I had the queer thought that the world was beginning to resemble a very large television studio. Everyone I knew was executive producing themselves on screens, whether affixed to cathode-ray and flat-tube TVs or the tiny LCD windows on flip phones; sometimes the cameras were merely other people’s eyes. While I brushed my teeth in front of the dorm’s bathroom mirror, trying to navigate my image in the pall of bright fluorescent light, I’d practice retorts to arguments my professors and peers hadn’t yet made, or reimagine previous exchanges when I hadn’t been quick enough on the draw. Every space I entered (classrooms, lecture halls, even bedrooms) felt like a green room, as if I were waiting in the wings for an invitation to speak, to make some declaration with as much conviction as I could. I was ever-ready to pounce and defend and assert my perspective, and wherever I turned, I heard yammering: people were making pronouncements. Although robust discourse is characteristic of college campuses, this pitched loquaciousness was in the ether everywhere then—at the mall, on the subway, at my hair salon—like the fog and gun smoke that drifts over battlefields in cinematic depictions of the Civil War.

So many people felt pride in being against each other. There was a sense, on the cusp of the 2008 presidential election, that something big was on the horizon, and the twenty-four-hour cable media ran up the hills, claiming to conduct reconnaissance for the rest of us. YouTube had launched only two years before, and I spent the wee hours watching music videos and viral clips, enthralled by the freedom to curate my own customized television network. In the break between my morning classes, I’d watch The View, and in the afternoon I’d catch the most explosive clips from the morning shows, cut up and distributed online. In the evenings, I’d sidle up in front of Countdown with Keith Olbermann or the news roundups on Current TV, and hate-watch The O’Reilly Factor and Lou Dobbs Tonight. I remember my freshman year as a procession of disembodied heads, their mouths perpetually in motion and also, oddly, agape: Tay Zonday, Sarah Palin, Michael Eric Dyson, Ann Coulter. In those years before Twitter launched, there was so much to discuss: the 2008 primaries, the Jena Six, whether or not Soulja Boy was destroying hip-hop, the way the Bushes and Clintons kept “passing the presidency around like a party joint,” as I recall Yasiin Bey, formerly known as Mos Def, saying on Bill Maher’s talk show.

In real life, the constant arguments, though often shallow and amateurish, could feel enlivening, unfiltered by the scrim and debate-prep performativity of corporate media. Even while disagreeing about whether or not something is an instance of modern lynching, or of “coonery,” it’s hard to affect a pose of roguish, faux-tough, kayfabe-style intellectual combat when your opponent is getting off at the same stop, or when you have to trust them not to accidentally nip you with a straightening comb, the smell of burning hair and grease raising the physical stakes. At least we were talking to one another.

One of the most bewildering aspects of that heady time was the constant debate about Barack Obama by Black pundits on cable news networks like MSNBC, CNN, and Fox News. I’d routinely see them making these appearances—particularly on Bill O’Reilly’s show, but it happened on liberal networks, too—only to be disregarded and even ridiculed once their segment ended. I didn’t understand why these men (and they were usually men) kept going where they were tolerated and not valued. The occasional meaningful exchange aside, the whole situation felt absurd, like a buttoned-up variation on pro wrestling. My impression of so-called public intellectuals in general, and certain Black talking heads in particular, was that they cared about screen time—getting famous or hawking their books—but were not really interested in critiquing the entertainment apparatus that the news was aggressively morphing into. Why didn’t they disentangle themselves from it all? If they had, they might have taken the rest of us kinfolk with them, and stopped allowing the Lou Dobbses of the world to use subjects that were important to us as rhetorical punching bags or fodder for ad-hominem attacks. I’m sure I didn’t articulate it quite this way at the time, but that was how I felt.

My sense of what a public intellectual could actually accomplish didn’t change until October 2013, when bell hooks was named the first scholar-in-residence at the New School’s Eugene Lang College of Liberal Arts. She launched a weeklong residency there that month, followed by two more such visits in 2014, and another couple in 2015, when the appointment ended. The residencies were organized around the themes of Black women’s bodily autonomy, feminism, and transgression, and saw hooks in dialogue with prominent cultural figures, including Janet Mock, Cornel West, Gloria Steinem, Melissa Harris-Perry, and Samuel R. Delany, as well as students from Eugene Lang and other institutions around the country. The events, generally ninety minutes long, were recorded and uploaded to the New School’s YouTube page. Watching from Los Angeles, where I was in a graduate writing program, I found them thrilling: there were discussions of Black love, the work of decolonizing public schools, and Pablo Freire’s philosophy, as well as critical engagement with popular films like Steve McQueen’s 12 Years a Slave (2013). By that time I had read hooks’s work, and watched a few televised interviews she had done in the nineties, but hearing her and her guests reason out loud, in real time—riffing, citing, moving from certainty to the exploration of still inchoate ideas and back again—was something else altogether. I’d never seen anything like the New School programming: it was electric to witness.

Among the things that set hooks apart from the other folks I’d encountered on TV was that she shared my suspicion of the “public intellectual” pose, questioned its political efficacy and the criteria by which certain thinkers were assigned the title. “I don’t see myself as a public intellectual, and I don’t talk about myself as a public intellectual, but I’m interested in the fact that other people are framing me [in that way] all the time,” she said, at the start of a 2015 talk with Laurie Anderson and Theaster Gates. “I could spend a lot of time trying to establish how I see myself, as opposed to how I am seen or categorized by other people… it’s been interesting to feel like that’s not my task. That actually takes me away from my task, which is the work.” I’d rather not be one of the people framing her that way. But I’m fascinated by hooks’s insistence on rejecting the term even as she redefined it, putting in the real work of advancing ideas in public forums and then interacting with those who responded to them. As she explained in a 2014 conversation with the artist Arthur Jafa, “My work is my passion, it is my calling. But it is not just like it’s all about me, or all about celebrity or fame or something like that … it’s about what the work does. My feeling of a sort of ecstasy is not in the writing itself or the thinking itself, it’s about hearing from people about what the work does. And then I know that yes, I am responsive to my calling, to what I’m put on this earth for.”

In the session with Jafa, hooks deconstructs a scene from Tate Taylor’s James Brown biopic Get on Up (2014), in which Brown, played by Chadwick Boseman, is upset that he’s been asked to open for the Rolling Stones at the 1964 T.A.M.I. show, despite his superior fame. hooks describes Brown’s private turmoil in the dressing room, then the moment of inspiration when, waiting in the darkness next to the stage, he decides to “flip it”—to subvert the billing he’s been given. He will overshadow the Stones by opening with a show-stopper, a set that would be impossible for them to follow:

And then he gets this flash, and he says, “We have to flip it.” To me, that’s the moment of critical intervention where he reimagines himself. And so, his reimagination, his flipping it is [that] he comes on so strong, so powerful, that no one can deny his presence, his visibility, his power as an artistic genius in that moment… I was charmed by that, because I was thinking about how so much of my life has been about flipping it. You know, saying I want to write books, and people saying, “N***** gal, who do you think you are?” Thinking that I can have sexual freedom as a young Black woman and having a group of Black men pull me off the street and say that to me, “N***** gal, who do you think you are?” And that constant sense of basically their saying to me, “Get back into the frame.” And me having to make a decision: Am I going to get back into the frame, or am I going to invent a way for me to live my life freely?

“Flipping it” can take many different forms. In a residency panel titled “Are You Still a Slave? Liberating the Black Female Body,” which featured Shola Lynch, Mock, and Marci Blackman, hooks spoke about marketers “flipping the channel from the hate channel to the voyeur channel,” commodifying and profiting from people with marginalized identities. Over many years, I tried to make my own less cynical shift, flipping the channel and tuning out the mechanized rage of the pundits, instead engaging with media that promised to produce a countervailing effect, as hooks’s residency videos did. Watching them felt like stretching out, intellectually. They seemed to act as an anti-inflammatory, letting viewers see more of the speakers’ humanity, make more allowances for mistakes, and gather the evidence we’d need for more informed critique. In their capaciousness, the videos themselves amount to a kind of clearing.

One of the quotations that made the viral rounds in the wake of hooks’s death, a redefinition of the word queer, comes from the “Are You Still a Slave?” event: “‘Queer’ not as being about who you’re having sex with—that can be a dimension of it—but ‘queer’ as being about the self that is at odds with everything around it and [that] has to invent and create and find a place to speak and to thrive and to live.” When I was a teenager, I understood the Q in LGBTQIA to refer almost exclusively to the term “questioning” but in recent years, “queer” often seems to have supplanted it. Of course, as hooks’s statement suggests, queerness and questioning, in the sense of critical inquiry, are intimately related. To ask questions is to be an agent in one’s own destiny, a crucial step in any attempt to find meaning within that existential at-oddsness hooks evoked. As she said in a 1997 conversation with the Media Education Foundation, “Thinking critically is at the heart of anybody transforming their life.”

Niela Orr is a story producer for Pop-Up Magazine, an editor-at-large of The Believer, and a fellow at the Black Mountain Institute. Her writing has appeared in the London Review of Books, The New York Times Magazine, BuzzFeed, McSweeney’s Quarterly, and The Baffler, where she writes the “Bread and Circuses” column.

Copyright

© The Paris Review