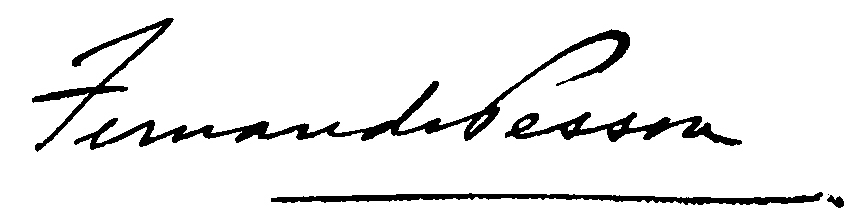

Fernando Pessoa’s Unselving

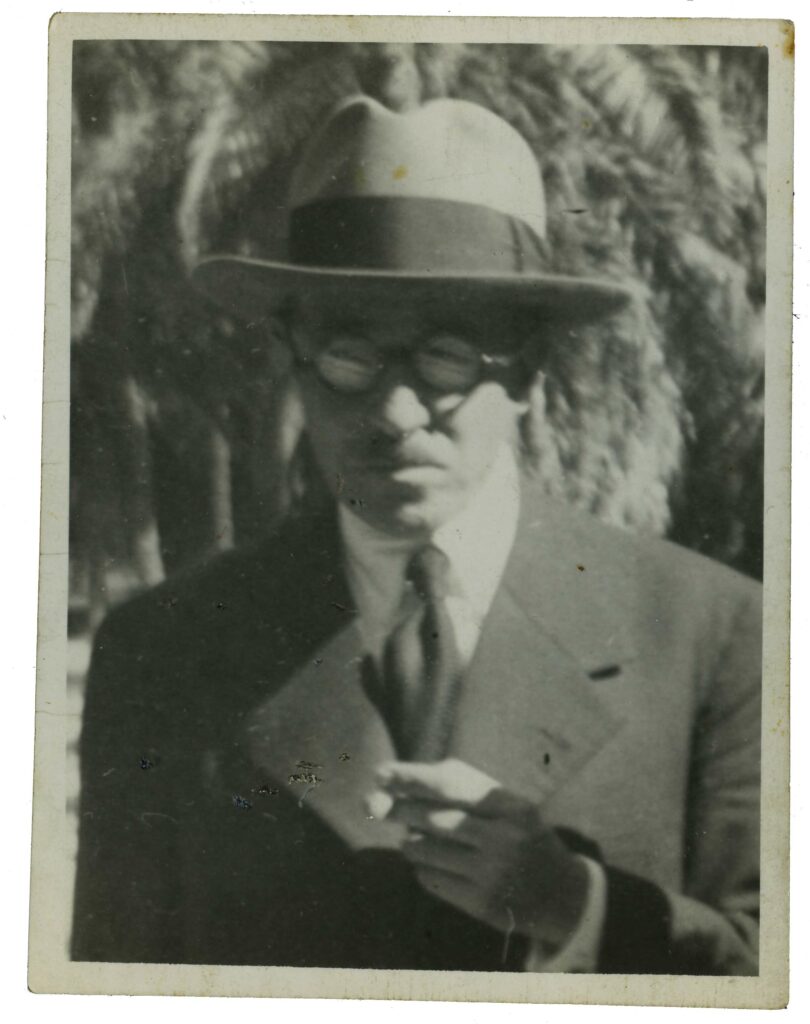

Pessoa in 1934. From Os Objectos de Fernando Pessoa | Fernando Pessoa’s Objects by Jerónimo Pizarro, Patricio Ferrari, and Antonio Cardiello. Courtesy of the Casa Fernando Pessoa and Dom Quixote.

On July 11, 1903, a long narrative poem called “The Miner’s Song” by Karl P. Effield appeared in the Natal Mercury, a weekly newspaper in Durban, South Africa. Effield—who claimed to be from Boston—was actually none other than the Portuguese writer Fernando Pessoa, then a high school student in Durban. This was the first of Pessoa’s English-language fictitious authors to appear in print—the beginning of Pessoa’s unusual mode of self-othering. The adoption of different personae allowed him to go beyond a nom de plume, and take on unpopular, controversial, and even extreme points of view in both his poetry and prose.

While in South Africa, where Pessoa lived between 1896 and 1905, he sent another work to the Natal Mercury under the name of Charles Robert Anon, attempting without success to publish three political sonnets about the Russo-Japanese War of 1904–1905. Pessoa’s early fictitious authors wrote in English, French, and Portuguese—the three languages he continued to use until he died, at age forty-seven. These first invented writers, which he would go on to call “heteronyms,” composed loose texts mostly in the form of first drafts; but others, like Bernardo Soares (whom Pessoa created around 1920) or the major heteronyms (Alberto Caeiro, Álvaro de Campos, and Ricardo Reis in 1914), produced a very solid body of work. By the time Pessoa was twenty-six years old, he had already invented a hundred literary personae.

Alberto Caeiro was the central fictitious figure of Pessoa’s literary universe. Born in Lisbon on April 16, 1889, Caeiro died of tuberculosis in 1915. Pessoa said that Caeiro poetically arrived in his life on March 8, 1914—which in a famous letter to the Portuguese literary critic Adolfo Casais Monteiro he described as a “triumphal day.” The poet and novelist Mário de Sá-Carneiro was one of Pessoa’s closest friends in Lisbon, and Caeiro (perhaps a pun on Sá-Carneiro’s name) seems to have come into being as a joke: “I thought I would play a trick on Sá-Carneiro and invent a bucolic poet of a rather complicated kind,” wrote Pessoa in the same letter. Caeiro’s “death” seems to have been influenced, in retrospect, by Sá-Carneiro’s suicide in Paris on April 26, 1916. As Pessoa wrote in the review Athena in 1924, “Those whom the gods love die young.” By that time, he had produced the body of poems for which Caeiro would be remembered—The Keeper of Sheep.

Courtesy of Tinta da china.

Then there was Álvaro de Campos, the most prolific and eccentric of Pessoa’s heteronyms. In the aforementioned letter to the critic, we find the most complete description of him: “Campos was born in Tavira, on October 15, 1890…. He is a naval engineer (by way of Glasgow)…, tall (5 feet, 74 inches—almost one more inch taller than me), thin and a bit prone to crouching…. [He is] between white and dark, vaguely like a Portuguese Jew; [his] hair, however, is smooth and normally pushed to the side, [he wears a] monocle…. He received an average high school education; then he was sent to Scotland to study engineering, first mechanics and then naval.” Álvaro de Campos was a self-indulgent and bisexual dandy who celebrated the modern world with its roaring of machines and the hustle and bustle of city life.

Courtesy of Tinta da china.

Pessoa links Campos to an array of literary influences, “in which Walt Whitman predominates, albeit below Caeiro’s,” and wrote that he had decided Campos to produce “several compositions, generally scandalous and irritating in nature, especially for Fernando Pessoa, who, in any case, produces and publishes them, however much he disagrees with such texts.” Undoubtedly Campos was Pessoa’s most sardonic and fierce of the heteronymic voice, sharing biographical facts with Nietzsche (also born on October 15) and affinities with Blake (“Like Blake, I want the close companionship of angels”)

The literary works of Campos may be split into three phases: the decadent (dandy) phase, the futuristic phase, and the pessimistic (existentialist) phase. Campos shows mixed affinities with Whitman and the Italian futurist F. T. Marinetti, mainly in the second phase: poems like “Triumphal Ode,” “Maritime Ode,” and “Ultimatum” praise the power of rising technology, the strength of machines, the dark side of industrial civilization, and an enigmatic love for machineries. In the last phase, Pessoa qua Campos reveals the emptiness and nostalgia that may come in the winter of one’s life. This was when he wrote poems such as “Lisbon Revisited” and “Tobacconist’s Shop,” the long, nihilistic poem of defeat written in 1928 and published five years later in the review presença. Considered one of the monuments of modernist poetry, it opens thus:

I’m nothing.

I’ll always be nothing.

I can’t even hope to be nothing.

That said, I have inside me all the dreams of the world.

Although Campos wrote poetry and prose in Portuguese, he also used English and French in some of his lines and titles. Among his most noteworthy prose writings we find “Notes in Memory of My Master Caeiro,” published in the Presença journal in 1931. In these notes, Campos offers an elucidating description of himself:

I am exasperatingly sensitive and exasperatingly intelligent. In this respect (apart from a smidgeon more sensibility and a smidgeon less intelligence) I resemble Fernando Pessoa; however, while in Fernando, sensibility and intelligence interpenetrate, merge and intersect, in me, they exist in parallel or, rather, they overlap. They are not spouses, they are estranged twins.

In the same letter to Casais Monteiro from 1935, Pessoa provides a detailed description of Ricardo Reis, his third major heteronym—defining him as a doctor from Porto, born in 1887, educated in a Jesuit college, and living in Brazil since 1919, out of fidelity to his monarchical ideals. Pessoa also adds to this portrait that Reis learned Latin through someone else’s education—probably with the Jesuits—and Greek by himself. These details serve to humanize the classicist Reis, the serious, measured, and semi-indolent Reis, who should embody a neoclassical theory opposed to “modern romanticism” and “neoclassicism in the manner of [Charles] Maurras.” Reis wrote epigrams and elegies, in addition to odes, and his poetry is largely characterized by the use of specific meters (especially the regular use of decasyllabic verses alternating, or not, with hexasyllables). Pessoa-cum-Reis wrote a substantial body of poetry and prose. Among the latter we find texts on paganism as well as the oft-cited essay “Milton Is Greater Than Shakespeare.” In his prose Reis makes a vehement claim to Hellenism and issues a firm condemnation of Christianity. He criticizes Matthew Arnold, Walter Pater, Friedrich Nietzsche, and Oscar Wilde, among others—a kind of predecessor to contemporary neo-pagan aesthetes and theorists who are not entirely freed from Christian sentimentality.

Courtesy of Tinta da china.

***

Fernando Pessoa’s modernist epic is the result of a radical displacement of the subject, which he described as a “drama in people”—made up of the poetic trio and his other aliases who Pessoa gradually crafted between languages, a vast collection of books, and Lisbon—the beloved city of his birth.

Following the publication of The Book of Disquiet in 2017, I met with the New Directions vice president and senior editor Declan Spring in New York City suggesting that we bring out Pessoa’s major heteronyms in the same order that Pessoa himself had birthed them. Thus, we started with Alberto Caeiro, master of the coterie. While The Complete Works of Alberto Caeiro came out in the summer of 2020, The Complete Works of Álvaro de Campos is forthcoming on July 4, 2023. These three Pessoa books—all including some facsimiles from the Pessoa papers held at the National Library of Portugal—will be followed by The Complete Works of Ricardo Reis.

In translating Pessoa’s heteronyms, one thing we see clearly is the influence of reading on Pessoa’s plural and inquiring mind. I have no doubt that reading more than writing was his primary and long-lasting literary occupation. His marginalia are of great interest; so are his many influences. This is to say that the more we know about what Pessoa read and when, the better equipped we are as translators of his works—especially to see more clearly his poetical diction, meters, and rhythms at the core of each heteronymic voice.

Courtesy of tinta da china.

On November 29, 1935, while lying in bed at the Hôpital Saint Louis des Français, Fernando Pessoa wrote his last words: “I know not what to-morrow will bring.” In the translation of an epigram by Palladas of Alexandria, published in the first volume of the Greek Anthology and still in his private library, we read the following pencil-marked closing line: “To-day let me live well; none knows what may be to-morrow.” Whether this depicts the consummation of a life consecrated to literature or the memory of Pessoa, it reconfirms the fact that Pessoa’s writings emerged from an intense contact with a vast array of books. His work has reconfigured literature, including the way we look at literature. May our century be one for such multitudinous Pessoa.

The Complete Works of Álvaro de Campos by Fernando Pessoa, edited and introduced by Jerónimo Pizarro and Antonio Cardiello, and translated from the Portuguese by Margaret Jull Costa and Patricio Ferrari, will be published by New Directions in July. Ferrari has translated Fernando Pessoa, Alejandra Pizarnik, and António Osório, among others. He is a polyglot poet, translator, and editor, resides in New York City, and teaches at Sarah Lawrence College. Ferrari is currently working on “Elsehere,” a multilingual trilogy.

Poetry and prose quoted from The Complete Works of Álvaro de Campos (2023) and The Complete Works of Alberto Caeiro (2020) by Fernando Pessoa. Used with permission of New Directions Publishing.

Copyright

© The Paris Review