Driving with O. J. Simpson

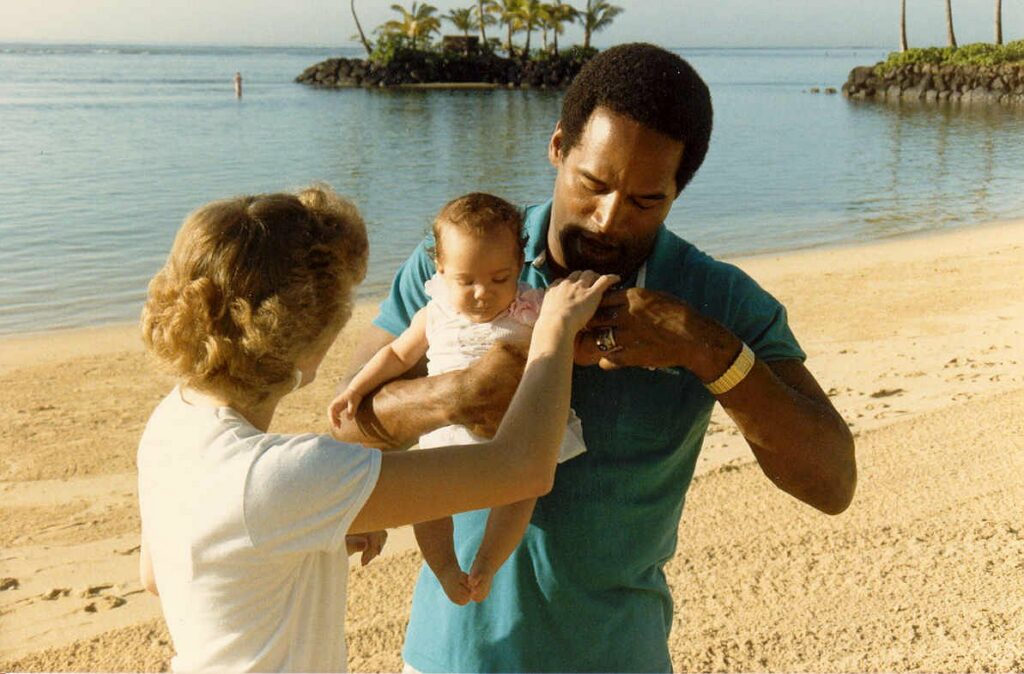

O. J. Simpson, Nicole Brown Simpson, and Sydney Simpson at the Kahala Hilton Hotel in Honolulu, Hawaii, February 1986. Photograph by Alan Light. Via Wikimedia Commons, licensed under CC0 2.0.

My father and O. J. Simpson were passing ships in red Corvettes in Brentwood, Los Angeles. Circa 1977, the sunroofs of their nearly identical luxury cars open for maximum exposure, they would wave to one another like carnival jesters, my sister in the back seat squeamish at the irony, their white wives occupying the front seats in a Siamese dream, twin stars in the fantasy no one is aware of until it arrives in images. Such gestures were the requisite scenic signifiers for that era of post–New Negro black entertainers faced with the hedonism of psychedelia, blaxploitation, and the amphetamined economy of the Reagan years. They were transitioning from taboos to tabloids to well-adjusted, literal tokens, having made it to some sense of after all or ever after in a fairy tale blurring the wasteland upheld by the lucky-bland amusements of almost-suburbanites. Unkempt and illicit ambitions were their freedom and retribution.

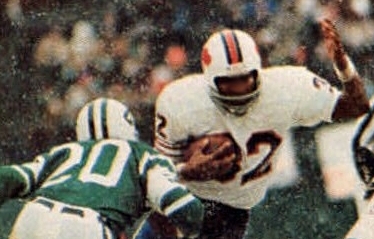

My father earned his living writing love songs that were ventriloquized by pop stars and peers such as Ray Charles; he agonized over the banality of spectacle in lyrics that rendered the banal uplifting. O. J. cradled footballs and ran very fast when chased, bowlegged, baffled at his own momentum. He accrued enough of it to become the first black athlete to garner corporate endorsements from companies like Hertz. He’d open in the typical format of vintage commercials, by reciting semi-didactic pleasantries as adspeak. Then he’d embody his embargoed alter ego, his own personal starship and space shuttle, and ramp up to cinematic sprinting through an airport terminal, wearing a three-piece suit and landing in a hideous car that made the Corvette with the top down seem like an inaccessible yearning, all while maintaining the plastic smile of a catalogue model. O. J.’s sad and vaguely distracted gaze revealed a self-deprecating narcissism contracted during the transition from being bullied as a child to outrunning everyone and every limitation he’d ever known. This was before it was acknowledged that the cerebrum of football players and boxers are often severely damaged and inflamed by the time they retire—and likely throughout their careers—in ways that can trigger bouts of rage, dementia, confusion, memory lapse, erratic dissociation. The talent, the miracle of divine intervention, that grants them access to white America’s lifestyle, in turn holds them hostage in pathologized exceptionalism. This makes it easier to understand the fatigued and dejected glaze over O. J.’s gaze as a mask dressing a festering internal wound.

My father’s gaze was similar, confident but strained and distant, almost plaintive. He’d spent some years as a welterweight boxer, which may or may not have contributed to his struggle with bipolar disorder and the constancy of lithium prescriptions of varying strengths—pharmaceutical cocktails, which, in addition to tempering his mood swings, siphoned the vigor from him, bending his will toward a docility more unnerving than rage. O. J’s double consciousness remained slicker and more protected; he made his icy sublimated anger into his signature charm even as it remained in part involuntary. As I write this, O. J.’s remains are being cremated in Las Vegas, and scientists have requested the opportunity to examine his brain for signs of chronic traumatic encephalopathy (CTE). The Simpson family is refusing. O. J. himself was convinced that he did suffer a level of chronic swelling consistent with the condition and severe enough to compromise his cognition and memory. There is no logical way to deny his intuition about this, considering the length of his career (he spent eleven years in the NFL and was a collegiate player before that) and the minimal number of blows to the head required to trigger a lifetime of chronic swelling. While considering O. J. and my father as twin victims of their own ambitions, I wonder how many blows to the skull, how many subtle fractures my father endured, and would I want to look inside and see the tissues ballooning for myself, would I allow doctors to dissect his brain for proof or defer to suspicion and leave space for the sacred/sacrosanct black-and-blank mystery of our destiny? I can’t be sure.

O. J. Simpson, then the Buffalo Bills’ running back, rushing the ball against the New York Jets on December 16, 1973, breaking the NFL’s single-season rushing record. Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons.

Some retired NFL players with severe cases of CTE become suicidal, go through with it, and shoot themselves in the heart so that their brains remain intact to be studied, blamed, perhaps so their souls are disabused of some turmoil. I imagine my father’s and O. J.’s waving hands in their twin Corvettes as their euphemistic version of throwing up reciprocal gang signs or channeling their shared elegance as ghetto mysticism. If they could get by with disguising themselves as happy-go-lucky all-American Negroes gentrifying Brentwood, they assured one another telepathically, they could exceed that. The excess could be lethal, or it could remain glorious; this was the risk of surpassing the confines of the lot they were handed at birth. Why settle for affability and sports cars, why not blend convention with sin and dysfunction and really have it all? They fade out into sunsets and party din, the lull of elite motors, the scoffing giggle of unimpressed bystanders.

***

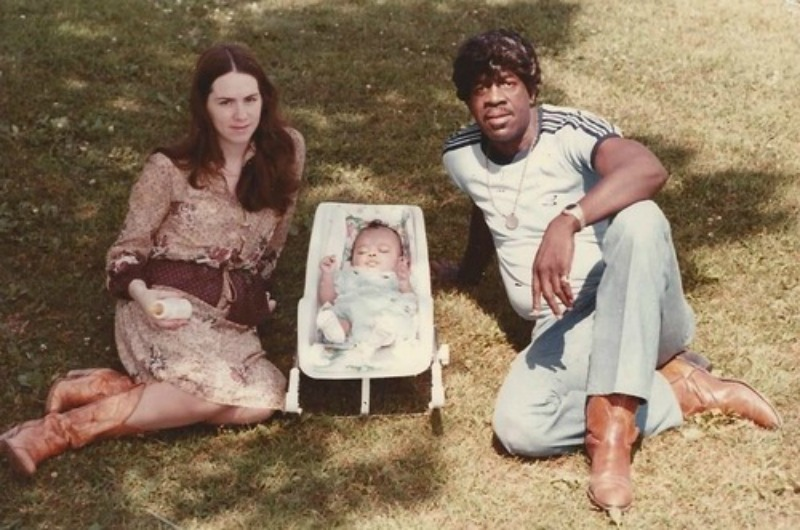

America needs black sociopaths, and breeds them, as much as she needs and breeds white ones and interracial love on her jagged and insincere path to approximating an egalitarian society stabilized by its consistent deference to spectacle. No renegade and formerly-oppressed minority group makes it in the USA without a few representatives or sentinels who are sanctioned to explore deviance with impunity alongside the so-called elite. And some invent an axis where desire, race, and criminality are forced to confront one another and try to survive or outwit the ensuing clash between ego and instinct. My parents met the same way O. J. and Nicole Brown did. My mother was a part-time waitress during college, and one night my dad was a lonely customer at the diner where she worked (as I imagine it, I hear Joni Mitchell crooning, “I am frightened by the devil, drawn to those who ain’t afraid”). They were married not long after that. Nicole Brown was waiting tables at an LA hotspot called The Daisy when O. J. came in one night. They were together from that point on, even though he was still married to his first wife during the early stages of their courtship. Neither woman knew her suitor was any kind of celebrity on first encounter. By all accounts, both couples began happy, and effortlessly transgressive. A young white woman, a much older black man with money and status. Children next. There I was, in the spring of 1982, less than a year after my parents met. Nicole gave birth to Sydney, her first child with O. J. in 1985.

“She doesn’t look like a black baby, O. J.,” Nicole Brown Simpson, captured on a now-retro camcorder, proclaims in the delivery room just after giving birth to their daughter, Sydney, in Los Angeles. Can a black star or his daughter be so lucky or sheltered or race-card-never-played-and-plagiarized as to experience emergence into human consciousness casually, instead of as casualty of close scrutiny for ruins? Unlikely. Nicole isn’t disinheriting her daughter in interrogating her lighter shade of brown; she seems genuinely concerned or perplexed, as if she might have inflicted an ambiguous pallor onto a soul who never asked for the burden of two worlds announcing themselves simultaneously as one skin. O. J. continues filming and celebrating, delighted and unfazed, as though he’d had a premonition about this auspicious event—the all-American and his gorgeous blond wife and nearly passing daughter are his paradise lost and recovered. He beams with the pride of a man reinvigorated by the birth of his child—he’s forty-one, a perfect age for a second wife and a second chance at a picturesque nuclear family. There’s omniscience in the delivery room, haloing it—Exhibit A.

Family photograph, 1983. Courtesy of Harmony Holiday.

By that same year, at the age of four, I was mistaking for adventures our family trips to precincts to have bruises examined by police officers. We didn’t get out much. Unless Dad was manic or hired to make some recordings; then we’d drive from Iowa to LA in two days without stopping. The red Corvette had been lost in the divorce from his first wife, but dad sustained the entitlement and urgency of a man who had once owned everything. He would leave us later that year, like one of those retired players who rips his own heart out after it breaks—a ruptured aneurysm, a burst of red light in the wounded cranium.

My mother and Nicole Brown were born the same year, 1959, the year Billie Holiday died, the year the spirit of integration Billie introduced by singing “Strange Fruit” at Café Society came back to warn us from the other side. So my mom and Nicole were both 35 in June 1994, when Nicole was brutally murdered. My mom remembers the night of the killings because it was also her dad’s birthday, but maybe the memory is so vivid because one sleight of the hand of God or the Devil and that could have been her. Night after night before my dad died it almost had been. He’d been dead seven years by that summer and she was a widowed single-mother alcoholic pre-K teacher raising two children in Los Angeles. The pictures of a bruised-up Nicole Brown Simpson were not unlike those of my mother’s blue-and-yellow face mending from a night of blows. You can make out both beauty and agony beneath their swelling and jaundice, a rebellion against being defined as victim, a subtle aggression akin to vengeance in the eyes that made them reluctant to beg for mercy too often. Like my mom, Nicole had tried calling the LAPD during outbursts, but O. J. often talked his way out of incrimination when officers arrived. And the gaze and policing went both ways in civilian life. As a white woman alone with black kids, my mom was often accosted in supermarket parking lots and asked if she had abducted us. We didn’t always say no so readily. I was somewhere else in the spirit, a fugitive, obsessed with dance lessons and dissociating from our chaotic household, where New Age practices like meditation, chanting to Enya, and eating meat substitutes made of tofu competed with her harder-to-kick habits—cocaine, liquor, and dangerous men.

It was always black industry-adjacent men, some as famous as or more famous than my father, some deadbeats chasing fame who saw my mother’s comfort with them as their come-up occasion. Though she had every intention of being a good mother, she was failing at that and at self-actualization by conflating the act of mothering with that of mating with an imitation of the deceased father of her children. But her efforts were sincere. Trying can be as valid as succeeding in the crucible of mothering and being mothered, I decided, in order to get through it. She was eventually fired from her job as a teacher at a private school where her students included the children of Jamaal Wilkes and other NBA players, after which she spent years in a debilitating depression lying to her parents and siblings, pretending she was still working, living on royalties from Dad’s music, some money I made when I was cast in commercials, and, when that failed, regular trips to the pawn shop to exchange expensive items my dad had given her for money toward the upkeep of some, if not all, of her habits. Like Nicole Brown, my mother dabbled in modeling, and I recall her headshots, which I placed in the plastic casing of one of my school binders as a kid, like a propaganda pamphlet—the one for French class, so that whenever we read passages from Les misérables and put new vocabulary words into morose Hugoesque sentences, there she was, judge and jury. That’s my mom, I would beam, reminding myself too.

As Sydney Simpson had been the night before Nicole was killed, I too was frequently performing at dance recitals in LA in 1994. One account, in a memoir written by Nicole’s best friend, who was in rehab when she died and spoke to her on the phone the night of the murder, tells us that Nicole had tried to enforce a boundary with O. J. at the recital. This enraged him. There are other murmurs suggesting O. J.’s son Jason, from his first marriage, might have been the real killer. He was supposed to cook everyone dinner after Sydney’s recital that night, the rumor implies, but they opted for the nearby restaurant Mezzaluna instead, leaving Jason dejected and resentful. At the time, he was on probation from his job as a chef for allegedly threatening his boss with a knife, and he was the only other family member for whom O. J. hired a lawyer. He had recently stopped taking his medication Depakote, which was prescribed to treat both the seizures and the intermittent rage disorder with which he’d been diagnosed. Some infer the notorious glove and hat were his, hence them famously not fitting, and that DNA evidence was either planted or matched because it belonged to the defendant’s son. Some suggest that he acted with his father’s blessing, or at least his knowledge. Some blame another man, Nicole’s handyman, who was also a serial killer who targeted blonds. It’s said that he confessed to the crimes, both to the police and to his brother, but was dismissed in favor of the blockbuster suspect. Still there are those who hold all of law enforcement accountable, the system that allowed for the televised beating of Rodney King, which had catalyzed the LA riots two years earlier, in the spring of 1992; insinuating that the not-guilty verdict was the retaliation of jurors and citizens given the chance to manipulate justice in their favor for once. I remember watching the riots on television while safely in West LA, which at the time felt like another country. It was hard, with what I’d already seen, to be shocked by violent eruptions. My eyes followed the slow-moving Bronco as if it was a whale in the sea about to come up for air or suffocate us all. The whole scene felt very matter-of-fact and in keeping with what I knew of my own father—pent-up and stifled black power would find its way to the center by any means necessary, was my sense of it. That cavalcade of crisis in the early nineties was almost a relief to me because I didn’t yet have the means to alert those around me to the fact that rage was always there, always coming, never letting up except when transmuted into song, dance, sprint, scream, and even then only temporarily alleviated. I watched calmly like watching a resurrection you know is coming.

During the slow-speed chase I’m on O. J.’s side in that I don’t want to see another black man who reminds me of my father die trying to outrun his demons: I want him to put the gun down. I rewatch the footage now and notice that when they do reach O. J.’s estate, before he turns himself in, his Bronco is intercepted by a distressed and flailing Jason—he approaches the car looking for his father as if he needs to confide something or get contraband to him. He’s histrionic and indelicate and promptly ushered away like a mendicant might be. Everybody is somebody’s decoy in this scene, and what was vaguely thrilling and confounding to watch on live television back then feels transactional now, and unremitting, an excessively long take with no one calling “Cut!”

***

The afternoon of the verdict, back from school where we celebrated and left our classrooms screeching approval and embracing like an innocent family member had just been freed, I’m running through the halls at home cheering, giddy, Freud has abandoned me, no one could tell me I wasn’t avenging some unnamed psychic baggage with that joy. I didn’t realize what I was rejoicing, reliving—my narrow escape from being the daughter in that legend, and the darker more elemental possibility that I was on O. J.’s and my father’s side, whether I liked it or not, in color and lore. I would defend them the way their wives had in front of their children, family, and friends even though I had endured the confusion of witnessing that self-betrayal as loyalty. Every witness became a helpless accomplice in the myth of peaceful reconciliation across racial and gender divides, in the name of love and one big happy lethal American family. I was one of those children, after all, watching her mother excuse her abuser to return to him for the good of her children, or so she told herself, and later even us, the cliché disclaimer that excuses so much pain in the name of union. Women in a battered women’s shelter were pictured on the evening news cheering gleefully on their sad sofa over the not-guilty verdict, like hired extras. I can’t remember my mother’s reaction on the day of. I never asked, or if I did I half listened to her answer and went on leaping and lingering in the perceived win. The redemption symbolism. Were my fellow travelers the men or the women or the children or none or all of them at once? How would we come to know who was good and who was evil in relationships that began as love and devotion and ended in death and dispersion? In a parallel universe my mom and Nicole wave at one another from sunroofs, and you can hear Nina Simone through a speaker somewhere reminding brown baby when you grow up, I want you to drink from the plenty cup. We oblige.

My mother is more of a ghost because she’s survived. When I was thirteen, not long after the O. J. trial, she had another daughter with an aspiring music producer who worked as a security guard by night but quit his job once he got serious with her. She bought him expensive studio equipment and for a couple of years he made mediocre demo tapes that, though I tried to ignore them, I found almost heartbreaking in their limitations. He was a veteran, skilled at crafts and household repairs, and eventually became a cobbler at Rancho Park Golf Course in LA. I found this heartbreaking, too, or maybe I felt betrayed at having to observe what felt to me, as a child who refused to lie to herself when I could help it, like a diluted version of my father encroaching upon my household, buying keyboards and samplers with my dad’s posthumous royalty earnings only to make songs that went nowhere.

He was trying his best and that somehow made it worse for me. My dad had the air of going from glory to glory even at his lowest points, swinging between triumphs—a new wife, a new hit song, a new idea, a new heir, a new commercial or film with his song in it. It’s made my sense of “you’ve either got it or you don’t” almost reflexive. I can feel it within aspirational people the moment I meet them, how far they might go and what trait will take them there, where they might self-sabotage and plateau at the limit of their talent. What it is that the best artists and athletes and even the most captivating philistines possess, is a manner of exerting the personal will, a willingness, that is akin to flying with no net beneath you to the tune of a corny jingle like Chet Baker’s “Let’s Get Lost,” or a sleeker sonic logo like Miles Davis’s version of “Bye Bye Blackbird.” When it is absent, exertion is futile. You’ve got it or you don’t, and it can include all the trouble that accompanies it, trouble which is often fetishized or mistaken for an indication of impending breakthrough. I tell myself I inherited it to get by. At Rancho Park Golf Course, my mom’s new common-law husband would run into the recently exonerated O. J. almost daily. They became friends. He’d fix and shine O. J.’s cleats, receive big tips and big disaffected Hertz rental smiles. It breaks my heart.

The day O. J. died I texted my mom “end of an era.” And we marveled at all the ways that’s true for us. I realized there’s no way she could have watched that trial in anything but irreverent despair, one of her modes, and when I celebrated the verdict unabashedly it was in part to neutralize her authority over me. No one seemed to care as much as I did, how that trial changed the course of pop culture, brought us the Kardashians, brought us to our knees, forced the conflation of heroism and disgrace to become an inescapable tenet of Americanism. We’ve since come to rely on the shadows of our favorite antiheroes to save us from ourselves or restore us to ourselves until justice for these American psychos we invent, then study, together, is that they allow others to experience their prevailing complacency as a virtue. At least they’re not all killers and pop stars who birth deeper ambiguity into the bloodlines of the descendants of slaves, the Greek chorus whispers, ignoring the collective obsession with the dark stars.

When I picture my father and O. J., black-on-white-on-red in the slurred sepia of nineteen-seventies West Los Angeles, the new Negro settlers, brash, elegant, perfect, ridiculous, free to express every formerly curtailed desire, I feel like a voyeur, like I might be their prop, doing exactly what they wished by writing this, by remaining ambivalent and refusing to condemn anyone. All that duality, all that beauty, all those you’re in danger girl stares have, for me, turned into nostalgia for the source of that danger. Then comes this reunion-scene-dread because there will be no reconciliation except with an absence, a cast of haunts. Could Sydney and I wave at one another from this treacherous distance, across terraces, like jesters, or searchlights dimming in thick fog? Then fade out into the grunge-era uniform of tutus and Converse high-tops, white lace socks, pink Capezio shrugs, aloof facial postures to compensate for trauma? So much of our right to a happy ending is tied up in the need for inconclusiveness to persist, and to allow for impossible forgiveness, the kind that demands we remain naive on purpose, never grow up, grow up so fast, stunted, endlessly elaborated. This inheritance of the sins of our fathers which we’ve turned into heartbreak, bravery, wave forms, music. It’s an infinitely renewable girlhood that skips like a broken record and loops not guilty, not guilty, we will not be guilty. Cut.

Harmony Holiday is a writer, dancer, archivist, filmmaker, and the author of five collections of poetry including Hollywood Forever and Maafa. She’s a staff writer for Los Angeles Times’ Image and 4Columns. She’s currently writing a biography of Abbey Lincoln for Yale University Press, a memoir on music, and a new collection of poems.

Copyright

© The Paris Review