Doodle Nation: Notes on Distracted Drawing

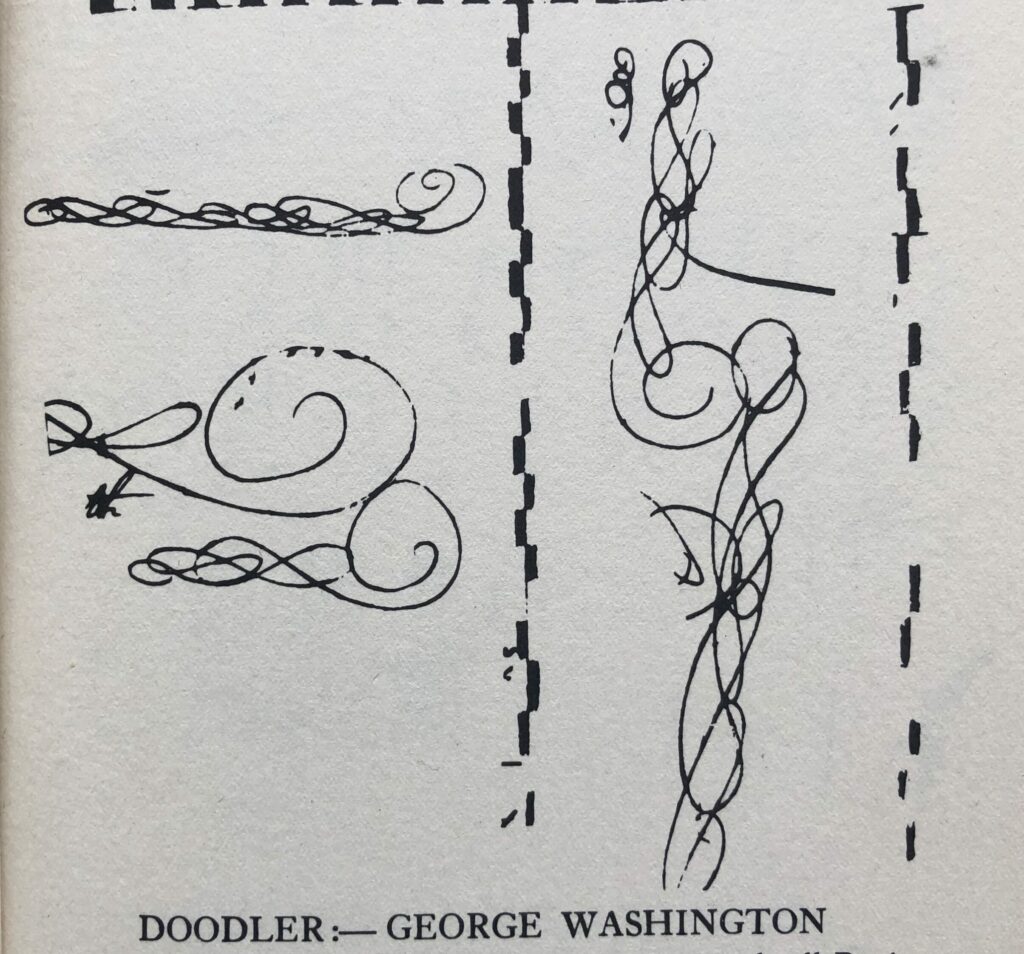

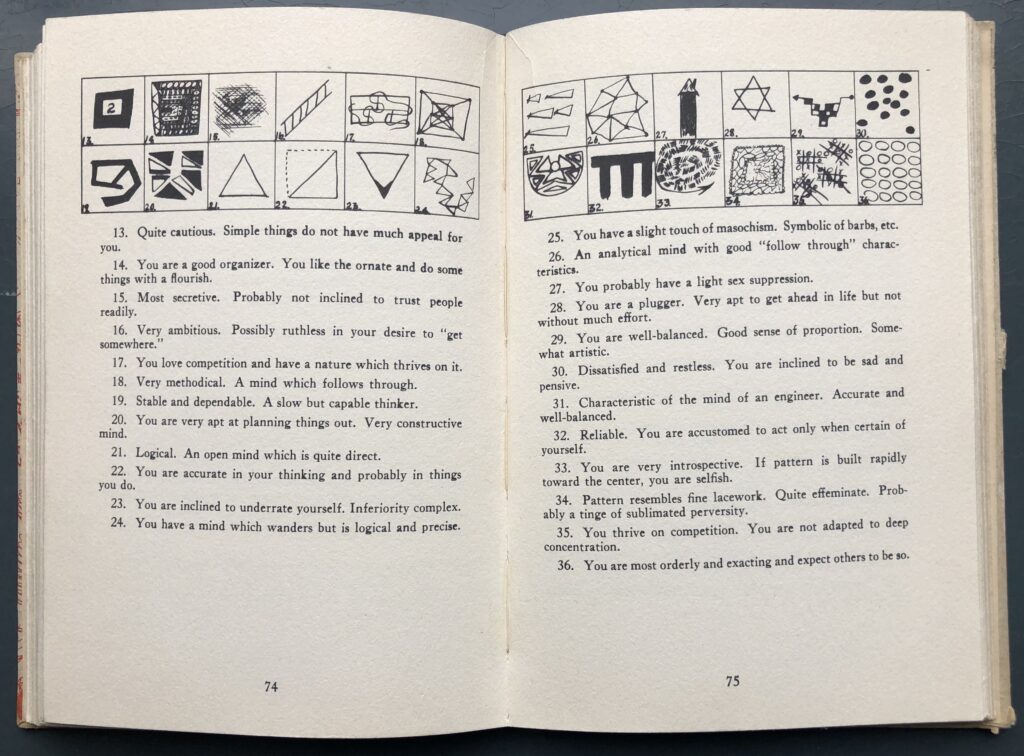

Some doodles by George Washington. Page from Everybody’s Pixillated: A Book of Doodles by Russell M. Arundel, 1937. Photograph by Polly Dickson.

Doodling today is not what it was. Or is it? Google “doodle” and you’ll find the Google Doodle—what Google calls a “fun, surprising, and sometimes spontaneous” transformation of its logo by a team of dedicated Doodlers to commemorate significant, and not so significant, days: from the seventy-fifth anniversary of the publication of Anne Frank’s diary to “Chilaquiles day.” You will also find a long list of apps that take Doodle as their name, including the ubiquitous scheduling tool. This recasting of the word in the age of the internet takes us far from the freewheeling squiggles, squirls, and whirls decorating the margins of telephone books and notepads—which is, perhaps, what doodling once was, in some near-unimaginable bygone era, when we worked with pens and pencils on paper, and when our attention and our hands wandered in different ways.

“Doodling” describes an activity of spontaneous mark-making by an agent whose attention is at least partially directed on something else. It’s the doodle’s apparent spontaneity and whimsy, but also its complicated relationship to attention—that most anguished-over of modern commodities—that makes it ripe for exploitation by the marketing strategies of app-based companies. That is: the doodle is usefully positioned, around the edges of our work documents and our conscious thought, to help us think about how our minds wander and about what those forms of wandering might yield. In a self-styled “doodle revolution,” which she introduces in a TED Talk and a book, Sunni Brown, founder of a “visual thinking consultancy,” explicitly attempts to capitalize on doodling’s wayward energies. Brown praises the potential of doodling for the workplace, coining a technique that she calls “infodoodling” as a tool for honing the attention of workers and thus increasing their “Power, Performance, and Pleasure” (plus, presumably, productivity—and profit). The goal is to “unlock” the potential of “visual language” to realize the full potential of our brains and “to help [us] think” in different ways. Brown’s self-styled revolution sits within a broader trend toward rehabilitating the act of disinterested drawing, as a kind of salve to our frayed modern attention spans. The doodle-curious consumer will find online a baffling array of derivative self-help- and wellness-flavored “guides” to doodling, full of promises to help us “Discover [our] Inner Whimsy and Find Moments of Mindfulness,” as the Daily Doodle Journal has it, or to “enhance your creativity,” according to another notebook of the same name. Doodling, or: how to cash in on the mind at play.

The activity of distracted drawing was first named “doodling” at a very particular moment: in the 1936 Frank Capra film Mr. Deeds Goes to Town. To be clear, the word “doodle” already existed. It possibly derives from the German dudeltopf, meaning “simpleton,” cementing a strand of aimlessness or surplus value that persists in its current form. Before the twentieth century, it was used to refer to a “simple or foolish fellow.” It is in a courtroom scene toward the end of Mr. Deeds Goes to Town that the word was coined in its current meaning: distracted drawing. The film’s oddball protagonist Longfellow Deeds has been proclaimed insane by his relatives for, amongst other things, playing the tuba and giving away his inheritance money. In his defense, Deeds argues that he plays the tuba to help himself think, and points out that everybody is subject to such inane, or insane, distracted fiddlings (or in the idiom of the film, “everybody’s pixillated,” meaning something like “away with the pixies”). Not least pixillated of all is the court psychotherapist, Emile von Haller, who has been trying to make a case for Deeds as a manic depressive. It is the psychotherapist’s own doodle that Mr. Deeds triumphantly exposes in the film, calling von Haller a “doodler,” which, he explains, “is a word we made up back home to describe someone who makes foolish designs on paper while they’re thinking”:

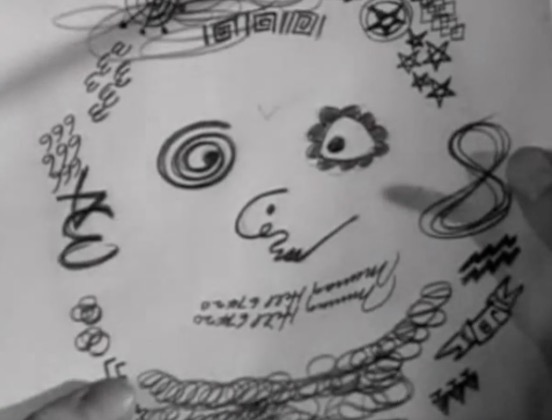

From Mr. Deeds Goes to Town. Screenshot courtesy of Polly Dickson.

Our modern understanding of a doodle thus has its premise in a fictional work. What Deeds shows us is the first doodle to be called a doodle, but of course it’s not one; it’s a drawing of a doodle. It’s as if here the scriptwriter has aimed to include all those archetypal forms that we are likely to find ourselves drawing when bored—stars, numbers, swirls, figure eights—drawing them together into the shape of a manic-looking face, such that it can be easily “read.” This gives it a satisfying finish, the snap of recognition. The fantasy of a doodle here, as a signifying system, bears witness to the investments we make in them—those investments have to do with clear, correspondent meaning. If it is mad it is also productive in a quiet and legible manner.

Whilst humans have presumably doodled for as long as they have written and drawn (the art historian Ernst Gombrich has studied the idle scribblings made by Napoli bankers on their ledgers in the fourteenth century), once psychoanalysis had begun to imagine the doodle as a key to understanding the unconscious mind, it was no longer possible to doodle innocently. Mr. Deeds Goes to Town, with its Austrian psychotherapist a parody of Freud, is a response to a frenzy for all things psychoanalysis in the thirties. Carl Jung, Hans Prinzhorn, and Alfred Adler had all previously written about the significance of our absentminded drawings or Kritzeleien (a word that is better translated as “scribblings”) in a psychotherapeutic context.

In Capra’s film, when Deeds asserts the universality of doodling and fidgeting, the doodle emerges, with its new name, from psychoanalytic papers into the Anglo-American mainstream consciousness. (Victoria Riskin has blogged about the “grave injustice” committed by the Merriam-Webster dictionary in failing to attribute to her father, Robert Riskin—the screenwriter of the film—the first use of the word in its current sense.) The doodle gained its name in a self-mockingly circular logic whereby the doodle is declared singular and meaningful only in order to show that the analyst himself is as mad as everybody else. All of this was in service of defending Longfellow on the charges of madness for having given his inheritance money away, drawing both money and doodles into the task of proving or disproving one’s madness. From this moment on, the doodle would continue to be caught up in an intensifying desire to make use of such drawings, to see what they might yield.

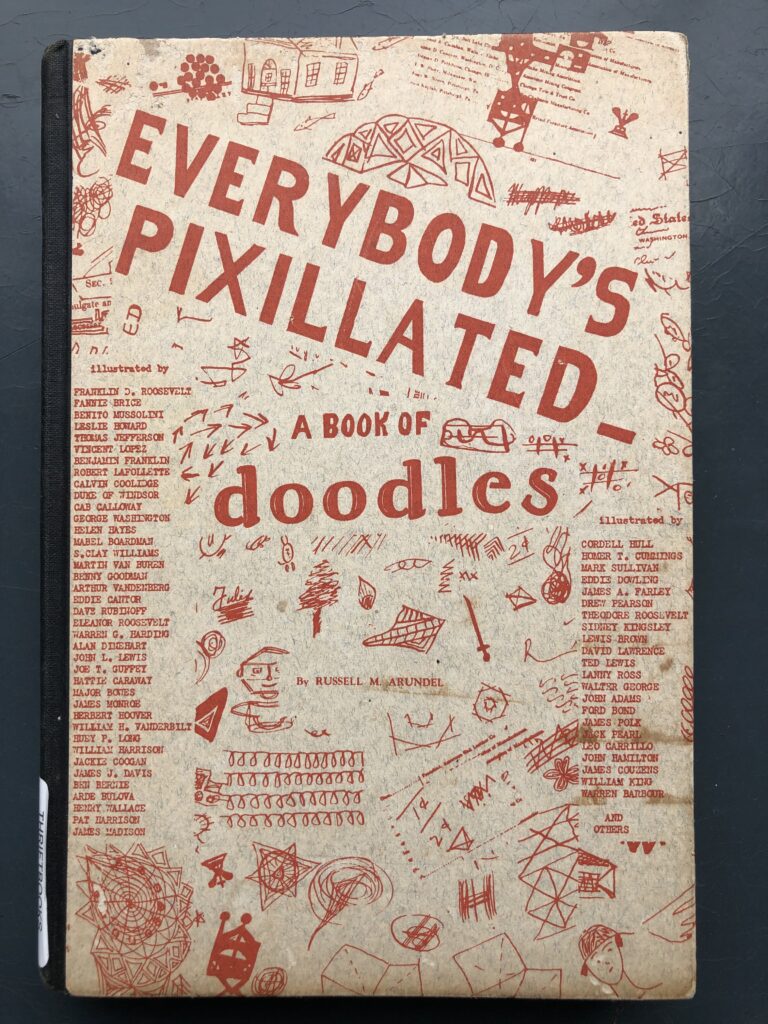

Cover of Everybody’s Pixillated: A Book of Doodles by Russell M. Arundel, 1937. Photograph courtesy of Polly Dickson.

A book that consolidated the word’s contemporary meaning is a strange, slim volume by Russell M. Arundel called Everybody’s Pixillated—a direct citation of Capra’s film—first published in 1937. Across its pages are reproductions of scrappy marginal drawings, documents of “priceless surrealism” sketched, scribbled, and doodled by presidents, senators, the Prince of Wales, lawyers, and other notable figures (almost all of them men).

Everybody’s Pixillated is both a paper exhibition of doodles and a whimsical manifesto in favor of paying attention to the chatterings of the unconscious mind. A case study at the heart of the book cements Arundel’s basic premise that doodles are pictorial clues to the secrets of what he affectionately terms “old man subconscious.” According to this story, a certain Private Marvin Shores liquidated his assets and buried the gold and silver bullion somewhere on his grandfather’s estate before going off to fight in World War I. When Shores returned in 1918, suffering from what was then called shell shock, his grandfather was dead and he had no memory of where he had buried his treasure. It was from the doodles he made during a telephone conversation—“crude drawings of rabbits, sketches resembling guns, and the word ‘booty’ ”—that a friend familiar with the secrets of “automatic writing” was able to help him unlock the location of his treasure: buried beneath an old rabbit hutch. Whether this little story is apocryphal or not does not really matter in the context of Arundel’s project. For it works as a founding myth of doodling and doodle-reading, justifying Arundel’s excavatory enterprise with the promise of unconscious treasure ready to be unturned. This version of doodling’s founding myth, like the scene in Mr. Deeds Goes to Town, is centered on capital. Paying attention to doodles will convert the apparent work of distraction back into attentional currency—and hard gold. This is the real work of making doodles mean.

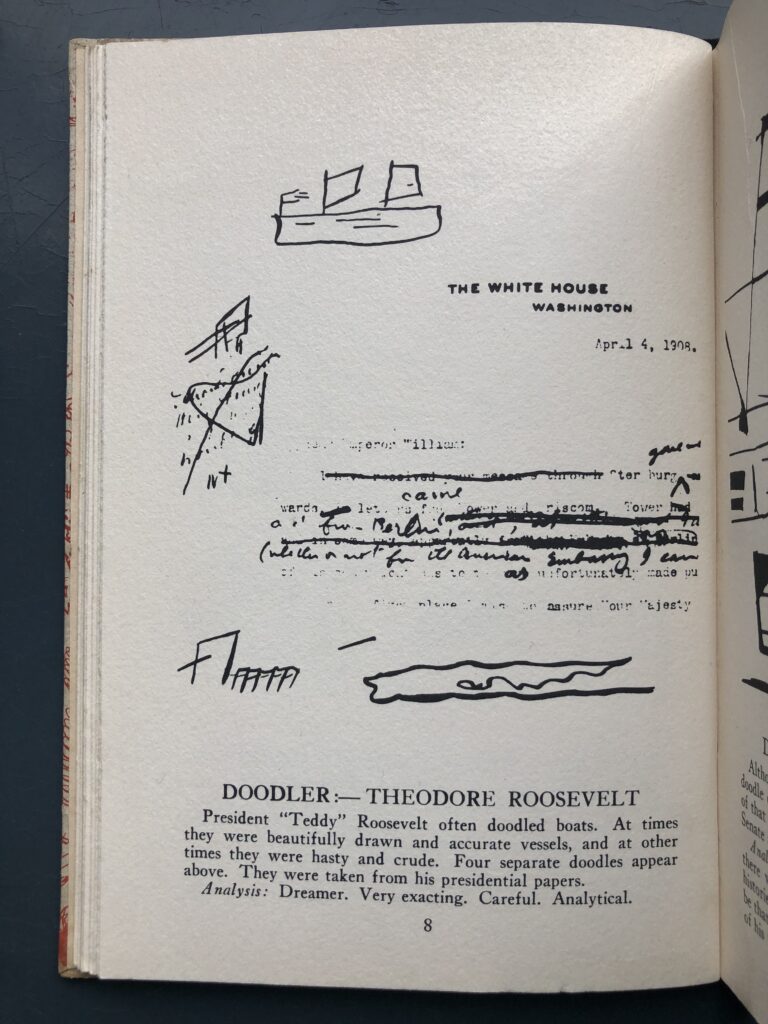

Arundel’s doodle book takes Riskin at his word, and is premised on the notion that everybody is inhabited by the compulsion to doodle. “This is a pixillated book for pixillated people,” he declares mischievously in the foreword. It is, in one sense, the document of one man’s obsessive pareidolia: that state of mind perched tantalizingly close to the state of paranoia, in which meaningless or random marks are configured into a message or picture, as when we catch a glimpse of a face in a wall or a buttered slice of toast or in a coffee stain. His analysis of Theodore Roosevelt’s boats and scribbles is delivered with a poetic sparseness: “Dreamer. Very exacting. Careful. Analytical.”

Page from Everybody’s Pixillated: A Book of Doodles by Russell M. Arundel, 1937. Photograph by Polly Dickson.

Are we mad because we doodle—even the most apparently rational minds amongst us, even those politicians whose drawings, some of them quite baffling indeed, feature in this book? Or are we mad because we are irresistibly drawn to such images and to the impossible task of decoding them? Here is another contradiction aroused by the doodle: that what seems like an intensely private activity can in fact trace our relationships to other people; that the doodle has a kind of social life.

Arundel was, by all accounts, something of an eccentric. Having worked as a lawyer at Capitol Hill, in the presence of the politicians whose scrappy papers he was able to salvage from the waste paper basket, Arundel was also the president of the Pepsi-Cola Bottling Company of Long Island, a keen hunter and fisherman, and, more surprisingly, founding father of the Principality of Outer Baldonia, a micronation in Nova Scotia that existed for twenty-four years. This odd episode in Arundel’s life is the story of a fabricated reality, an irresistible parody of nation building, that made Arundel into an unlikely hero of the Cold War.

In 1948, Arundel purchased for $750 a four-acre island off the Tusket Islands that he had come across whilst fishing. He called it Outer Baldonia, proclaimed himself Prince of Princes, and limited the citizenship of his newly founded principality first to men, then to tuna fishermen. Back in Washington, Arundel and his subjects managed to get their dubious male utopia onto an official map of Canada and drew up laws, a national flag, and a currency, the Tunar. They even sketched out a declaration of independence:

Let these facts be submitted to a candid world. That fishermen are a race alone. That fishermen are endowed with the following inalienable rights: The right of freedom from question, nagging, shaving, interruption, women, taxes, politics, war, monologues, cant, and inhibitions. The right to applause, vanity, flattery, praise, and self-inflation. The right to swear, lie, drink, gamble, and silence. The right to be noisy, boisterous, quiet, pensive, expansive, and hilarious. The right to sleep all day and stay up all night.

As a bit of hypermasculine silliness, this declaration of the legal rights of its citizens to lawlessness is written in the good-humored register of Carrollian hyperbole. It was also an immense feat of bureaucracy. When a writer of the Moscow Literary Gazette took (or seemed to take) the wording of the constitution seriously and declared Arundel a tyrant, Arundel responded, fully in the spirit of things, by formally declaring war on the Soviet Union. Needless to say, it all came to nothing, and in the seventies Arundel sold Outer Baldonia to a society for the protection of birds for a single dollar.

In both the doodle book and the fictional nation, Arundel rouses up the nonsensical underside of bureaucratic processes. Both are governed by a dreamlike, “pixillated” logic of overturning our expectations of paperwork. In the doodle book, he exposes the unexpected byproducts of writing, thinking, and paying attention; in the Outer Baldonia episode, he conjures up a fictional state that, on paper only, resembles a real one. Arundel was interested in the indiscriminate chatter that tangles and clusters at the edges of our conscious thoughts and decision-making processes. A significant portion of the doodle book is given over to an autographic history of the process of writing out an agricultural relief bill—or rather, the ways in which it is “doodled into shape”—and passing it through Congress and Senate. Arundel, in the guise of enthusiastic “doodlebug,” narrates this version through the doodles of its authors. Stately political processes, he shows, go hand in hand with the madcap arabesques, squiggles, and scribbles of politicians’ scrap paper. Doodling here is writing’s other self, its shadow form.

From Everybody’s Pixillated: A Book of Doodles by Russell M. Arundel, 1937. Photograph courtesy of Polly Dickson.

As much as they tell us about writing, doodles tell us about reading. They get at the heart of the critical act by seeming to solicit interpretation, then skittering away when we get down to the business of studying them. They might, after all, register no more than the inky imprints of the pleasures of mark-making or the necessity of testing the pen. Take a doodle too seriously, and you risk finding only your own desire for meaning bounced back at you. Despite Arundel’s tongue-in-cheek taxonomizing, and the earnest efforts of graphologists ever since, no systematic vocabulary for the understanding or critical interpretation of doodles, no Doodle Dictionary, has ever gone mainstream. And of course that’s the point. By telling us how to read them, Arundel is asking us a question about reading. It’s a fitting quirk of Arundel’s own life that in the Outer Baldonia episode he seems to have attracted, in the character of the Russian journalist, precisely the kind of exaggerated seriousness the doodle book flirts with (although, to be fair to the Russian journalist, nobody seems clear on whether he was engaging in satire of his own). For the book knows itself to be a kind of joke: its motive, he states on the first page, “is good humor.” “If the chart doesn’t happen to tell the truth,” Arundel reminds us, “just remember the foreword—‘This is a pixillated book for pixillated people.’ ”

Whether or not we see doodles as subversions of work, as what art therapist and historian David Maclagan (who has studied the history of the doodle) has called a kind of “graphic truancy” or “miniaturized graffiti,” or as hieroglyphs of hidden parts of the self, or as a way of unleashing hidden potential and maximizing our performance as workers—or as performing some other kind of work—the most fascinating things about doodles are the desires of their readers.

Pixillation attracts and engenders pixillation. This book about doodles is a book about how we pay attention to each other, about the forms of attention we are able to pay or give. Although Arundel’s book is a dazzling treatise on paying attention to parts of the human mind that cannot usually be caught and directed by such attention, at its heart, really, is the curious figure of the self-titled “doodlebug,” who pictures himself creeping gleefully between wastepaper baskets in the offices of congress, asking senators to hand over their scrap paper.

Polly Dickson is an assistant professor in German at Durham University. She is the author of Romanticism, Realism, and the Lines of Mimesis and is at work on a project on doodles.

Copyright

© The Paris Review