Does the Parent Own the Child’s Body?: On Taryn Simon’s Sleep

When we take pictures of our children, do we really know what we are doing, or why? The contemporary parent records their child’s image with great frequency, often to the maximum degree afforded by technology. Inasmuch as the baby or child is an extension or externalization of the parent’s own self, these images might be seen as attempts to equate the production of a child with an artistic act. The task of the artist is to externalize his or her own self, to re-create that self in object form. A parent, presented with the object of the baby, might mistake the baby for an authored work. Equally, he or she might find their existence in an object outside themselves intolerable. In both cases the taking of a photograph is an attempt to transform the irreducibly personal value of the baby into something universal by proposing or offering up its reality. Yet what the image records is not so much the reality of the baby as that of the person looking at it. If the baby or child is a created work, it is one whose agenda remains a mystery to its creator.

The actual representational value of the parent’s photographs might be minimal compared to their narcissistic and artistic functions. Yet in the act of photographing, the parent does aspire to represent. How can the child be expressed in such a way that others will recognize in it what the parent recognizes? The parent, having created the child, belatedly encounters the moral and technical difficulties of creativity. Her instinct is that the photographic act ought to be a selective one, recording only what the parent-photographer wishes to be seen and remembered. The result is something no one else would especially want to look at. The photograph is a half-truth, because it has omitted large portions of reality. Generally speaking, the parent’s attempt to express what they see and feel in looking at their child, to universalize those feelings, does not succeed. The parent may have thousands of such photos, just as a failed artist may have a roomful of unwanted canvases, which can find no place in the world.

An artist, in the consideration of her material, also confronts the difficulty of separating it from the conditions of her own existence, yet her instincts are the reverse of a parent’s. Rather than trying to control or interfere with what the viewer “sees,” her aim is to give total power to the image, so that it is capable of living independently in the world. A baby is already an independent being: despite its many needs, it doesn’t exist solely as a condition of the mother. The baby is already important, but not necessarily in a way that the mother can see or find acceptable. It is important in spite of its mother, not because of her. The mother uses the baby’s image as a way of changing the basis of this importance, and of proving that she created—and is still in the act of creating—the baby. When she sets out to express her baby or child in photographs or stories, the mother-as-artist is trying to re-attribute the material to herself. Thus, “her” child is more important than other children: the mother-as-artist enters into an unending battle, in which the ground of truth will be repeatedly desecrated as she attempts to prove this is the case.

An artist who is also a mother, forewarned of the difficulties of creation, confronts in her child a different kind of test. Her process uses the self as a kind of lens—a tool for seeing and verifying, something both carefully and pitilessly handled—that automatically engages with the child in search of its truth. But there is a problem, both in her ownership of the material and in the conditions of her access to it. Here, the roles of witness and author have been reversed: in her child she is witnessing that which she has in a sense authored. The overwhelming subjective bias of parenthood makes the task of representation virtually impossible. In any representation of her child, she will have to be wary of her parent self, who believes her own child to be the “important” one. Also, her success as an artist would signify her failure as a mother: to see her child objectively—as she would have to do in order to create art—would be to jettison the whole psychological mechanism whereby the mother renders the child’s existence tolerable to herself.

Taryn Simon’s Sleep navigates these snares by proposing parenthood as a state of copyright: a custodianship and right of access that will expire after a given time. Her images engage with the central enormity of the child’s being: its mortality. In the fact of the child’s body lie also the facts of loss and of nonexistence, as well as the possibilities of harm. The child embodies the risk of being alive. The parent-photographer, too, circles the implications of corporeality, attempting incessantly to “capture” the child’s body and thereby ensure or immortalize it. Importantly, this transaction usually requires the child’s attention or participation. The child is asked to smile or look at the camera, to collaborate in the photograph’s illusion of positivity, in which the child’s aliveness belies the prospect of risk. By collaborating, the child appears to agree with the parent’s point of view and with their ownership of the child’s narrative. To photograph a nonattentive child is instead to see their vulnerability and aloneness, to see them as they are.

In Sleep, the children are not only nonattentive, they are inaccessible, sealed into the privacy of the unconscious mind. By photographing them in the dark and seeing only afterward what the camera has seen, Simon regains the objectivity of the artist, and puts it into correspondence with the child’s own objectivity. For the artist-as-mother, this is a form of radical honesty, for she is relegated to the role of bystander and prevented from shaping the image or story of the child to suit herself and make her fears tolerable. It might be felt that the child’s sovereignty is being in some sense breached or invaded, since the collaborative signs of the parent-photograph are absent. However, the child’s usual participation in its mother’s narrative being more or less compulsory, what Simon’s images in fact show are the possibilities of the child’s freedom. Here the child is temporarily oblivious to, and unreachable by, the parent’s artistic and moral control.

A parent quickly learns that “seeing” entails the danger of something unwanted being seen, and of the story being ruined or compromised: the act of seeing is therefore rigorously controlled, so that the parent’s private knowledge of the child is separated from its image, which has been prepared for others to see. In Sleep this control, and the intentions behind it, have been abolished, and the mother shares her true powerlessness, admits the dreadful nature of her fears and responsibilities and her knowledge of what the child is. Here, this knowledge has been gained by her as witness, not as author: it has been gained only by virtue of her being there, and seeing things—through the lens—that she is unable to control or alter. In this knowledge, therefore, lies the truth, and a set of moral responsibilities that are entirely different from the responsibilities of parenthood. Here she is representing the child not as her property or as an object of overwhelming personal importance, but as an autonomous—almost an anonymous—human.

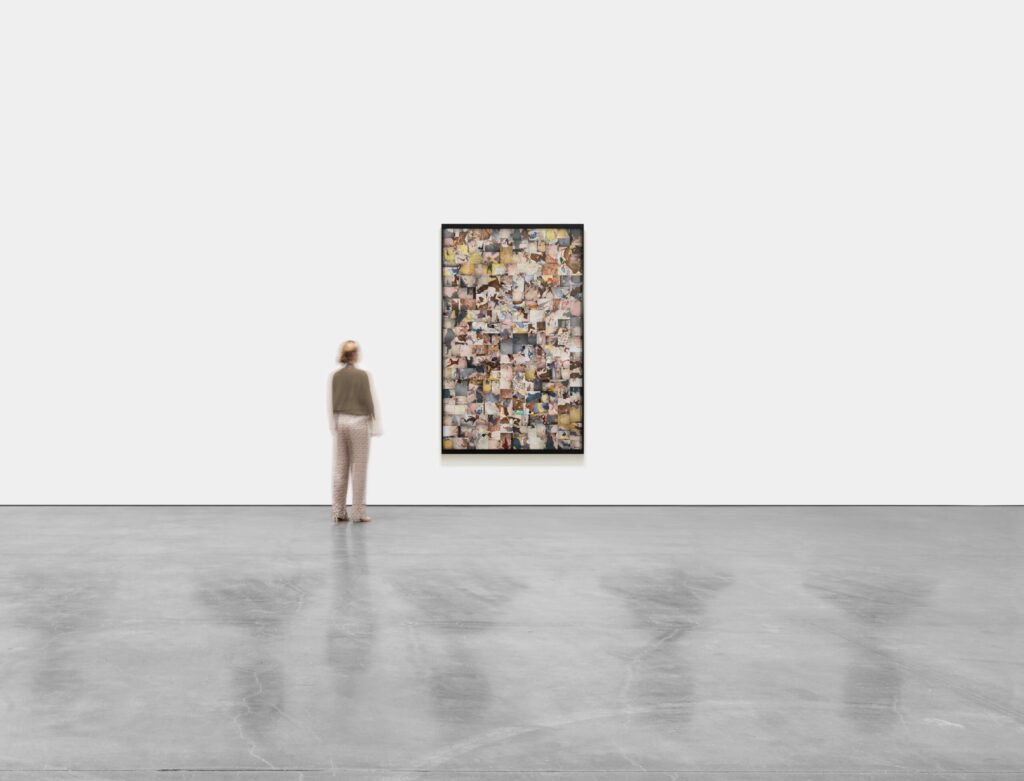

The world of forms in Sleep obtains a mesmerizing aesthetic: twisted in blankets and bed linens, the bodies at first resemble death. Their entanglement appears to suggest the end of resistance, a sort of drowning. The sight of their surrender immediately arouses our painful knowledge of mortality and of the ways in which we are forced to make this knowledge tolerable to ourselves in our daily lives. The bedclothes by turns shroud and reveal it, acting as a kind of frame or narrative structure, so that we are led deeper into the knowledge rather than rejecting it out of hand. The bedclothes represent familiarity and care: we recognize them, recognize what the act of covering signifies. A body is covered for the sake of modesty, of privacy—in waking life, in sleep, and in death. In Sleep the bodies have frequently fought free of or lost their coverings. Through this act of unconscious assertion, a new definition of the autonomy of the body emerges. In their entanglement the children’s bodies lose their unity, which is to say their identity. We see a limb, a hand or foot, a stretch of torso: the horror and beauty of these sights is offset by the bedclothes as medium, swathing or swaddling the identity-less limbs so that they regain a different kind of coherence. Like a domestic Sistine fresco, this swirl of bodies posits the spectacle of fleshliness against the intangibility of meaning. Instead of the miracle of identity and consciousness, we are offered the miracle of the body, its engineering and functionality, its ineradicable yet mysterious status as the domain of the self.

Having created it, does the parent own the child’s body? Who owns an artist’s work? The notion of copyright is helpful in understanding the way time creates and then destroys the illusion of possession. Having removed the question of identity—not just through the confusion of limbs but through the cropping away of faces—the images in Sleep return to this notion of ownership. The component parts of the child, and their altered meaning when divorced from the whole, offer the key to interpreting the child’s self-possession. Looking at these images, we acknowledge that the limbs must “belong” to somebody. What is a child’s leg, taken separately from the child? What would it mean for us to own it? We would never, for instance, photograph the leg—for the photograph, we must have the whole child. In this way we come to realize that the child is separate from ourselves and cannot be reintegrated into our creation of it. The child’s body can’t be broken up, however much its parents—in acrimony, for instance—might want to divide it. Likewise, a work of art suffers from an inviolable integrity that separates it from its creator.

We begin to look for other signs of identity in the images: the nightwear we presume the children have had some hand in choosing, the occasional object they have taken to bed with them. One of them has drawn something on its own stomach: are they, in fact, beginning to collaborate in their own way with this nightly recording of their image, speaking back to the lens by exerting some choice in the matter of what it sees? Yet the mystery of sleep is as dense for them as it is for us: each morning they will wake up not knowing where they’ve been or what they’ve been doing. The camera can offer some evidence, some clues, but in the end only deepens the mystery. It is a child’s question—Where do I go when I sleep?—that is also our own unanswered question about mortality.

But it is for its portrait of time itself that Sleep is most unnerving and revelatory. The images convey a stark fact: that the basis of maternal time lies in repetition. The mother’s days and nights represent an accumulation that is barely perceptibly an advance: it is as though she is living the same moment over and over again. Her vigil, her tormenting attentiveness—occurring in the strange prison of love—is the extraordinary sacrifice nature exacts from her. Her children’s nightly escape from that prison in sleep is the foretaste of a greater desertion. One day, having taken what they need from her, they will leave. Summoned away into the night, they are accruing the growth and power that will make that transition possible, while she roams the abandoned landscape of her care of them. Time no longer exists for her in that place of repetition: in her confinement there, however willingly undertaken, she is no longer time’s subject. Just as the lens has no story to tell, no agenda beyond its mere presence, so her own story—her experience—lacks even the most rudimentary illusion of progression. Yet in documenting that state, Taryn Simon has also located its rare and valuable privilege: the opportunity to acquire a selfless knowledge. The mother, should she choose to take it, has the chance to escape the bounds of ego and perception, and to arrive at a new truth. What she does with that truth, when her children have gone and her copyright has expired, when time begins to flow again through her life, is as yet unrecorded.

Rachel Cusk is the author of eleven novels, including Second Place, Outline, Transit, and Kudos; the memoirs A Life’s Work, The Last Supper, and Aftermath; and Coventry, a collection of essays.

Taryn Simon’s works, which incorporate mediums ranging from photography and sculpture to text, sound, and performance, are informed by research on and with institutions such as the U.S. Department of Homeland Security, the International Commission on Missing Persons, and the Fine Arts Commission of the CIA.

Copyright

© The Paris Review