Cooking with Taeko Kōno

Photograph by Erica MacLean.

The Japanese writer Taeko Kōno is a maestro of transgressive desire whose stories often—and deliciously—use food as a metaphor for sexual appetite. Kōno, who died in 2015, is considered one of Japan’s foremost feminist writers and one of its foremost writers of any kind. She won many of the country’s top literary prizes, including the Akutagawa, the Tanizaki, the Noma, and the Yomiuri. The single selection of her work in English, Toddler-Hunting & Other Stories, first published by New Directions in 1996 and translated by Lucy North and Lucy Lower, contains ten dark, deceptively simple stories about women who find the gender roles in Japanese society unbearable, and are warped by them.

Clockwise from top: kombu, fresh ginger, bonito flakes, shichimi togarashi, dried wakame seaweed, dried shiitake mushrooms, and shiso. Photograph by Erica MacLean.

Kōno’s heroines are abandoned wives, girlfriends who don’t want to marry, and women who lack maternal instincts. Her mothers are monsters. Her little girls feel “inner discomfort” with their gender. Most characters desire pain or humiliation during sex. In the collection’s title story, “Toddler-Hunting,” the protagonist’s boyfriend nearly beats her to death with a “vinyl washrope … the type with plastic knobs and metal hooks at either end”; still they both enjoy the varied sounds that objects make when they hit her flesh. In another story, “Theater,” an abandoned wife becomes part of a ménage à trois with a married couple who promise to degrade her. When the protagonist sees the husband kick his wife in the face, she begins “swooning” on the porch step, honored just to be standing there. Several of the stories contain pedophilic themes and fantasies of graphic violence against children.

A raw meat dish inspired by Kōno’s story “Ants Swarm,” photographed on a gallery poster by the Japanese artist Nobuyoshi Araki. Photograph by Erica MacLean.

The beauty of these stories, as I find it, is in the characters’ assertions of themselves against a society that has failed them. In Kōno’s time and place, to be an unwomanly woman was to have no social status, and yet her heroines are willing to transgress everything—to travel even to the boundary of death—to take something for themselves: maybe it’s self-definition, or simply pleasure. Kōno’s gentler moments simmer with possibility, as in the story “Night Journey,” in which a couple attempting to wife swap wander through their city at night, passing ruined structures like a half-constructed home and a dusty, disgusting temple before they head off into thrilling and uncharted territory. Her harsher moments can be nearly unbearable to read.

On a character eating oysters, Kōno writes, “She liked to hold the morsel of meat pressed firmly to her lips and feel her tongue become instantly aroused with the desire to have its turn.” Photograph by Erica MacLean.

Throughout these stories, Kōno uses food as a vehicle to discuss her protagonists’ bodies and desires. Sometimes it’s used metaphorically to conjure something dark: one character, dependent on an indifferent man, is compared to a trussed and roasting chicken. Another, after a pregnancy scare, is like a slab of raw meat crawling with ants. These women are trapped in situations of disempowerment and horror; for them, eating, among other forms of consumption, can be a means of escape. In the collection’s final story, “Bone Meat,” a woman nourishes herself on the scraps left behind by her partner as he eats oysters. Scraps of hinge muscle are more gratifying for the woman than the whole oyster, and they produce in her a kind of sensual ecstasy, followed by sexual ecstasy after the meal. This unconventional nourishment makes the woman plump and happy. In the story “Theater,” the protagonist harbors a desire to be struck and humiliated by her married friends; she attends a Christmas feast with them that includes “a splendidly garnished fowl on a large china platter.” During the meal, she watches the husband tie up his wife in the dining room, beat her, and even throw a “gnawed drumstick” at her. Our heroine desperately tries to think of “church bells,” but just before the curtain drops she “let[s] the fork fall from her hands with a clatter.” The husband turns to her, saying: “All right, all right … It’s your turn now.” In the story “Toddler Hunting,” the sadomasochistic narrator, who is disgusted by little girls, has prolonged, violent fantasies about little boys. In the story’s closing scene, she approaches a little boy eating watermelon on the street. Her lascivious ploy to share his snack while watching him probe the watermelon with his fingers will make any reader deeply uncomfortable—and yet the sequence’s final image is one of ecstasy.

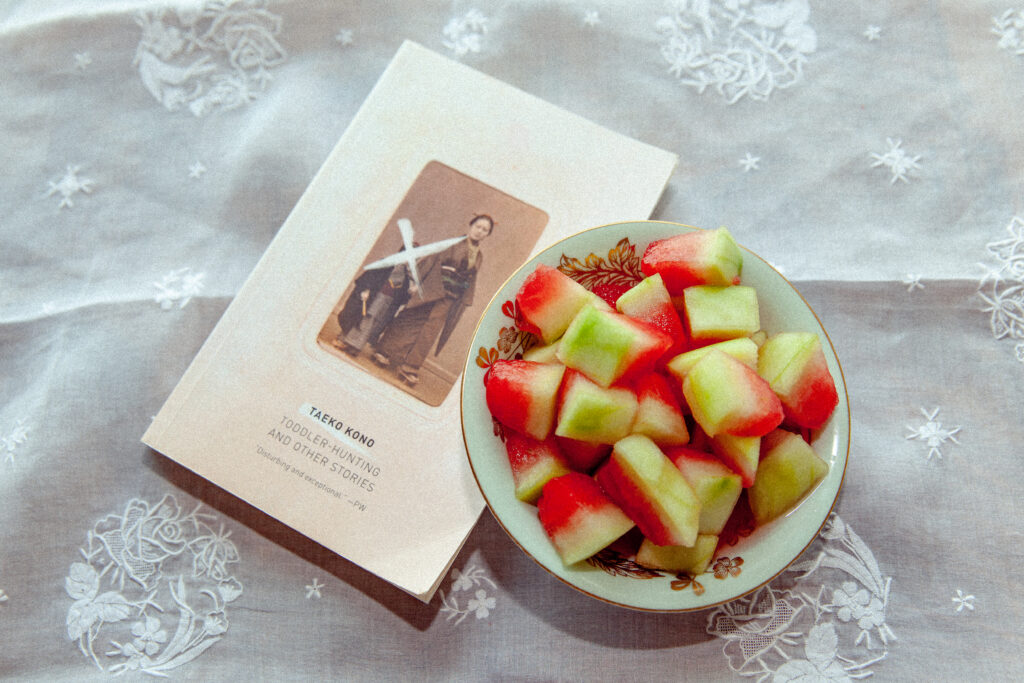

A Kōno character picks out every seed in a chunk of watermelon until it’s “mauled to an oozing red mass.” My modern version was seedless. Photograph by Erica Maclean.

It is Kōno’s genius that such epiphanies, difficult as they are, feel like a celebration of her characters’ humanity. To give us all a turn, in the culinary sense, I planned a menu from her work that would focus on flesh. I wanted a Japanese preparation for a whole roast chicken, a raw beef dish as a tribute to the steak in “Ants Swarm,” oysters à la “Bone Meat,” and a watermelon dish to reference the little boy’s discarded treat in “Toddler-Hunting.” I selected a showstopping recipe for a roast chicken that called for a forty-eight-hour marinade in shio koji (a type of fermented rice paste) from the cookbook The Japanese Larder by Luiz Hara. Elsewhere online I found oysters “three ways,” with toppings including grated daikon and powdered wakame seaweed. My beef would be a beef tataki seared for one minute per side and served with daikon and ponzu sauce. My watermelon rind would be quick-pickled. For drinks, which play a lubricating role in most of Kōno’s stories, my spirits consultant Hank Zona suggested a bottle of boutique sake from Brooklyn Kura and a bottle of Folium Sauvignon Blanc by Takaki Okada, a Japanese vintner making organic, handpicked, dry-farmed wine in New Zealand.

The swinging couple in the story “Night Journey” ask their friends to sleep over for the first time after drinking too much wine. Photograph by Erica MacLean.

Kōno’s work is sometimes stomach-churning, but my food made me ecstatic—though I didn’t throw my chicken legs at anyone, press my steak on any welts, or humiliate anyone in the consumption of oysters, so perhaps I was still missing out on some essential piece of it all. In the forty-eight hours the shio koji–rubbed chicken sat in my refrigerator, the rub’s umami flavor penetrated all the way to the bone. The resulting roast chicken was intensely juicy and tender. The spicy-bitter-briny toppings for my oysters were easy to whip up, and though I usually believe oysters are ruined by anything more than a squirt of lemon, in this case I found the multiple toppings enhancing. The rub for the beef tataki called for floral and exotic sansho pepper and an aromatic spice mix called shichimi togarashi. Encrusted in this, my seared meat was explosively flavorful when combined with salty-sour ponzu sauce.

To the protagonist of a Kōno story, ants on a lump of raw meat form “a single writhing mass again before her eyes, a black lump squirming obscenely, teasing and goading her on.” Photograph by Erica MacLean.

Then the wine brought all the flavors into focus, creating an intensely sensual experience worthy of Kōno’s work. The Folium, Hank explained to me, is a “dialed-back” New Zealand Sauvignon Blanc—it’s not as grassy or sharp as those wines tend to be, but lively and acidic, tasting of straw, salt water, minerals, and citrus. Such wines make great “food wines,” Hank said, in the sense that they separate and lift other flavors on the palate. Combined with the Japanese food, the Folium became peppery, with notes of yuzu, which made sense given that Okada sells mostly to the Japanese market. The Brooklyn Kura sake was botanical and more strongly alcoholic in taste, but it also complemented my food.

“Whenever Fukuko came across something particularly fresh or delicious, her first thought was to ask the Saekis over for dinner,” Kōno writes of her swingers. Photograph by Erica MacLean.

Despite how well everything turned out, I’m sure I fell down in some regards. My homemade dashi, a base broth made from kombu seaweed and bonito flakes, was especially a stab in the dark. The first recipe I tried asked me to consume an enormous and unrealistic amount of ingredients, and it was inedibly strong, not like other dashis I’ve tried. (The cookbook cautioned that there’s a huge variety in both price and taste when it comes to the bonito flakes; to make it successfully requires experience and familiarity.) The second version, made hastily with the leftover ingredients, was better, though it still lacked the subtlety and balance you’d find in Japanese home cooking. Overall my dishes were wonderful, but wilder and rougher than I suspect their traditional versions would be—which seems just right for Taeko Kōno.

Photograph by Erica MacLean.

Quick-Pickled Watermelon

Watermelon rind, with some of the red part still on for color

Salt

Shiso

Remove the outer dark-green part of the watermelon rind. Cut the remaining rind into ¾ inch cubes. Weigh the cubes, then calculate 2 percent of their weight in salt. Place cubes and salt in a zippered freezer bag, massage to distribute salt, and refrigerate for 1 hour. Top with shredded shiso leaves and serve immediately.

Photograph by Erica Maclean.

Oysters with Multiple Partners

Adapted from RecipeTin Japan.

Oysters, 1 dozen

Dashi stock

Kombu (seaweed)

Bonito flakes (dried tuna)

Tosazu dressing

Rice wine vinegar, 2 parts

Soy sauce, 2 parts

Mirin, 1 part

Bonito dashi stock, 3 parts (kombu, bonito flakes)

Photograph by Erica MacLean.

Spicy topping

2 teaspoons momiji oroshi (daikon radish, dried red chili)

2 teaspoons shallot, diced

Authentic topping

3 teaspoons shiso leaves, chopped in strips

2 teaspoons grated fresh ginger

Luxury topping

2 teaspoons chives, minced

1 teaspoon wakame seaweed, ground

2 teaspoons salmon roe

Photograph by Erica MacLean.

Make the dashi stock. You’ll use only a little bit of this. Reserve the rest for other purposes. Ingredient strength varies widely, and the following recipe is only what worked for me. Put one sheet of dried kombu in 6 cups of water in a medium saucepan and let it sit for 30 minutes. Discard the kombu, add one 2.5 gram packet of dried bonito flakes, and bring to a boil, uncovered. Immediately turn off the heat, strain, and cool.

Make the tosazu dressing. Combine all the ingredients for tosazu dressing and set aside.

Make the momiji oroshi. Peel and cut a two-inch chunk of daikon radish, large enough that you can hold onto it and grate it comfortably. Carefully cut a narrow indentation into the top of the radish, about one inch deep and just wide enough that you can stuff a dried red chili pod into the indentation. Grate.

Shuck your oysters, reserving as much of the brine as possible, and loosening the flesh from the hinge muscle so they slip easily from the shell. Arrange them on a bed of ice, drizzle each one with ½ teaspoon tosazu dressing, and add the topping combinations, making four of each variety.

Photograph by Erica MacLean.

Beef tataki

Adapted from Diversivore

For the ponzu sauce

50 milliliters yuzu juice

Lemon rinds and seeds

50 milliliters sake

50 milliliters mirin

100 milliliters soy sauce

15 milliliters rice vinegar

½ teaspoon white sugar

1 piece kombu (2 x 6 inches)

1 small handful bonito flakes

Photograph by Erica Maclean.

For the beef tenderloin:

¾ pound beef tenderloin

2 teaspoons dried shiitake mushrooms, ground

½ teaspoon shichimi togarashi

½ teaspoon black pepper

⅛ teaspoon sansho pepper

½ teaspoon salt

1 tablespoon vegetable oil

1 teaspoon sesame oil

About 1 cup mild radish, thinly sliced

3 scallions, white part only, cut into matchsticks

3 tablespoons ponzu

Photograph by Erica Maclean.

Make the ponzu sauce. Combine sake and mirin in a small pot and bring to a boil. Boil for 1 minute, then remove from heat. Add all the rest of the ingredients and set aside for as long as possible, at least for 30 minutes and as long as overnight. Strain out solids and refrigerate the ponzu. It will keep in the refrigerator for up to one month.

Bring the meat to room temperature. Cut across the grain into two steaks, sprinkle with salt, and set aside. Combine the dried shiitake powder, shichimi togarashi, black pepper, and sansho pepper in a small bowl. Rub the upper and lower surfaces of the steaks with the mixture. Heat the oils in a heavy-bottomed frying pan. Sear the steaks for 1 minute each side, then set aside to rest. Slice the steak as thinly as you can manage. Serve with onions, radishes, and ponzu for dipping.

Photograph by Erica Maclean.

Forty-Eight-Hour Shio Koji Roast Chicken

Adapted from The Japanese Larder by Luiz Hara.

1 whole, good-quality chicken

6 ounces shio koji (malted rice condiment), blended until smooth

2 garlic cloves, crushed to a paste

1 teaspoon sansho pepper

Photograph by Erica Maclean.

Combine shio koji, garlic, and pepper. Wash the chicken and pat it dry with paper towels. Place it on a plate that will fit in your refrigerator, rub all over with the paste, including loosening the skin at the neck and stuffing the paste beneath it over the breasts. Tent loosely with foil and refrigerate for 48 hours. When ready to cook, preheat the oven to 400 and bring the chicken to room temperature. Roast for 40 minutes covered with foil and an additional 20–30 minutes uncovered, until the skin is crispy and browned and the chicken is done. To test for doneness, insert a meat thermometer in the thickest part of the thigh. The temperature should be 165.

Photograph by Erica Maclean.

Valerie Stivers is a writer based in New York. Read earlier installments of Eat Your Words.

Copyright

© The Paris Review