Cooking with Sergei Dovlatov

“Dad did not care about food,” the daughter of the Soviet dissident writer Sergei Dovlatov once told me, vehemently, upon my suggestion that I might cook from her father’s work. I knew what she meant, but I also knew that Dovlatov’s books were full of the everyday food that was still current in Moscow when I first arrived there to live in the nineties, a few years after the collapse of the Soviet Union. Dovlatov’s characters pause during phone conversations to scream that someone not forget to buy the instant coffee (the only coffee available—I grew to like it). They drink—continuously—wine, vodka, beer. They offer each other bowls of borscht or “spear a slippery marinated mushroom” while talking, or order a sandwich, a salad, or a “chopped-meat cutlet” at a café. In one memorable scene near the end of The Compromise, an autobiographical novel about Dovlatov’s time working as a correspondent for the newspaper Soviet Estonia in the seventies, a full spread of delicacies for Communist Party elite comes out: expensive cold cuts, caviar, tuna, and a piped marshmallow dessert called zefir.

Open-faced sandwiches called buterbrod (from the German) were popular in immediately post-Soviet Russia. At the Bolshoi Theater they served them with orange caviar. Photograph by Erica MacLean.

Like everyone I know who has personal ties to the region, I watched with profound sadness and stress as Russia invaded Ukraine. I thought again of Dovlatov. Within Russia, he is among the most prestigious of the Soviet anti-regime writers, and is a household name. Born in 1941 to Armenian and Jewish parents, he grew up in Leningrad and worked primarily as a journalist. By the seventies, he was publishing fiction abroad, and circulating it by hand in photocopied format, as samizdat, in the USSR. This work drew government reprisals that left him unemployable, and he was forced to emigrate in 1979. His stories featured a depressed and often drunk narrator named Dovlatov and focused on the despair, hypocrisy, and absurdity of life—particularly life in the publishing industry and the arts—under a totalitarian government. I was working as a journalist during my time in Moscow, and everyone I met told me that I had to read him, specifically recommending The Compromise. Each chapter begins with a fulsome snippet of a fictional newspaper article written in the propagandistic style of Soviet newspapers, and is followed by the tragicomic story that unravels the propaganda. At the time, it was thrilling to believe that the forces of censorship had been defeated, and that Dovlatov and those like him had won.

A character in The Compromise eats marinated mushrooms while another passes out into a dish of potatoes during a drunken bender, the real story behind a fake story on a reunion of prisoners of war. Photograph by Erica MacLean.

Now, of course, those forces are ascendant once again. In the nineties, I identified with Dovlatov’s experiences working for Soviet Estonia; I was freelancing for women’s magazines and early websites, and my editors often wanted to massage the facts to fit the preferred headline or had loathsome criterion such as “Everyone in this piece has to be attractive.” I could relate to Dovlatov’s pain as he was forced to write about ideologically correct babies or to cover a funeral where the bumbling authorities bury the wrong corpse. “Dovlatov can write in a lively way about any kind of nonsense,” an editor says of him, as a compliment (translation mine). I knew just what that felt like. Today, I am nostalgic for such lighthearted concerns.

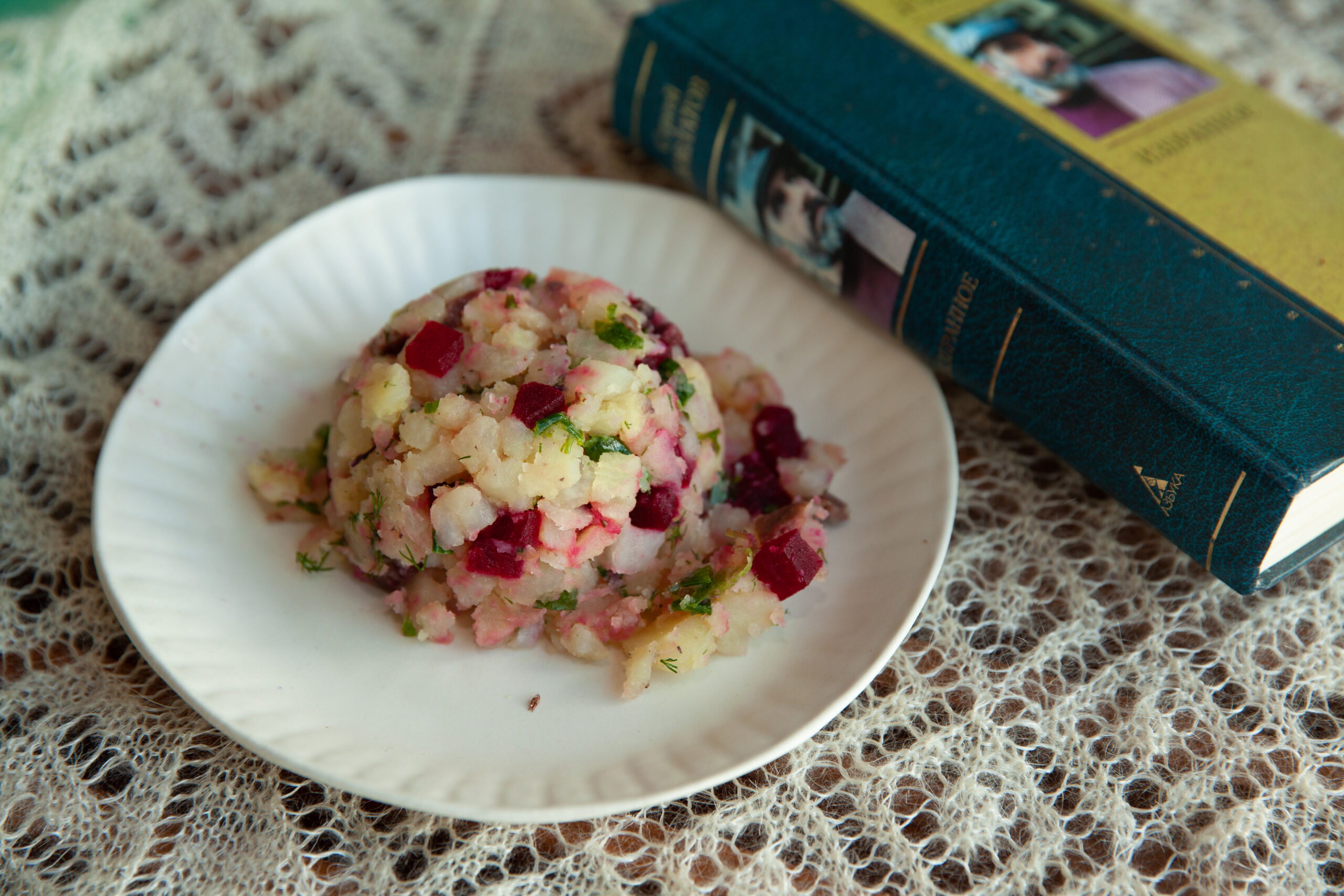

Dovlatov included culinary details because of the realist bent of his work. The potato salad I made from these ingredients was unrealistically good for food of the time. Photograph by Erica MacLean.

To combat propaganda and censorship, Dovlatov offers truth and craft. His fiction is written in clear, meticulous language; he lets events speak for themselves. The pitch-perfect deadpan humor is almost untranslatable, but many lines resonate with me. My favorite statement ever made about a day at the office is this one: “I continued to work without any special ardor.” I also laugh when an editor sending him on assignment asks, “Comrade Dovlatov, do you have a black suit?” Dovlatov replies, “I have a sweater.” Their truth is in these daily details—the protagonist is broke, drunk, depressed, semihomeless, doesn’t own a suit, is unable to get his fiction published, and is wasting his talents churning out foul propaganda. The gorgeous craftsmanship of the rendering is the commentary, revealing the Russian value of dukhovnost, a slippery word that I’d translate as the combination of culture, morality, and spirituality.

Flavoring elements included tons of oil, chopped dill and tarragon, black olives, and beets. (Tip: Mix in the beets just before service to preserve the color of the dish.) Photograph by Erica MacLean.

Dovlatov believed that dukhovnost was in direct opposition to “excitement about food,” his daughter says. For him, there were more important concerns than what a person was eating for dinner, and to imbue food with any serious significance would have been both laughable and low. (Writing fifty years ago in the Soviet Union, he would have had no inkling of the way our food today has become an ethical quandary.) The feast at the end of The Compromise, which included “the standard assortment of Central Committee allocations,” provided an opportunity for social satire. It occurs when Dovlatov and a photographer-sidekick Zhbankov are sent to a regional town to interview a super-productive dairymaid. Her achievement will be celebrated in a telegram to Brezhnev. Upon arrival, Dovlatov and Zhbankov are whisked off to a house of rest and greeted by two young women with party affiliations, there to have sex with the visiting bigwigs. Like the chocolate-covered marshmallow (zefir), such things were perks for communist authorities. When he sees the unaccustomed spread of food, Zhbankov says, “Serge, what have we got ourselves into?” Dovlatov replies, with withering irony, “What’s wrong? We’re simply moving up.” And then, “We’ve been given a serious assignment.” (The assignment, don’t forget, is a made-up story about milking a cow.)

“Everyone who thinks is unhappy,” Dovlatov writes. For the thoughtless, there were feasts like this one. Photograph by Erica MacLean.

Dovlatov partakes of the feast without comment: to take from the system that was taking from you was considered only fair. He sleeps with the girl, too, though it is a rueful experience. “It’s amazing how men are put together!” he observes, “Or am I the only one like this? You know it’s all lying, primitive Party sham and lying with a Hollywood patina over it. You know it all but you’re happy as a kid.” His aim is to truthfully portray humanity—and to make culture from even the lowest experience. This recalls for me the book’s prologue, in which he says of his work as a reporter: “Ten years of lies and dissembling. And yet, some people stood behind them: conversations, feelings, things that actually happened. Not on the pages themselves, but beyond them.” It’s the truth and the quality of the rendering that’s important, and that serves as a counterweight to the world of garbage and spin. In this sense, The Compromise is uncompromising.

The trick to cutlets “Kyiv-style” is to add riced potatoes as a thickener. Photograph by Erica MacLean.

I set out to try to reassemble the food in Dovlatov, doing my best on the quality of the rendering—cooking is an art form that Dovlatov may not have appreciated, but it’s my own. When I first encountered the type of Russian salads and cutlets and sandwiches he writes about, my suburban American sensibility found them both wondrous and awful. A Russian “salad” had no green leaves. A “cutlet” was a soft, oval ball of ground meat, scooped by the hostess from a bath of murky liquid. A “sandwich” was not a sandwich but a buterbrod, a heavily buttered slice of bread, topped by a curling bit of cheese or glistening balls of congealing orange caviar. In cafés, they were often left sitting out unrefrigerated. (Americans, I learned, are uptight about refrigeration.) Zefir tasted good—dessert is a universal language—but the marshmallow had a mysterious sour note. Later, living again in Moscow in the early aughts, I grew to appreciate these foods, especially in their home-cooked versions.

I made marinated mushrooms, buterbrod, a potato and beet salad, and, from a Ukrainian cookbook, cutlets “Kyiv-style.” I also attempted to make zefir at home, a process difficult to get right without a candy thermometer. I knew enough about Russian cuisine to predict—correctly—that the results would be mixed. Russian pickles and marinades, like Russian jams, are an arcane art. Each woman in the countryside does it in her own way, often from foraged or homegrown ingredients. My mushrooms were edible, but not authentic-tasting, nothing like the pickled mushrooms my Russian mother-in-law makes, with their additional notes of dill flower and blackcurrant leaf. The buterbrod, also, couldn’t be accomplished without commercially produced white bread and yellow cheese not available in the United States. They looked correct, but the single perfect flavor note, the salmon roe, emphasized that the rest wasn’t quite right.

The potato salad and the cutlets were inauthentic in a more successful way. Dovlatov ate his in a café in the seventies in Estonia. They probably weren’t very good. Mine were wonderful. The cutlet recipe called for riced potatoes as the thickener for the meat mixture, which was then shaped into ovals, rolled in flour, fried, and braised in stock. I made adjustments, leaving out the onions and changing the ratio of beef to pork, but this time it was a variation any grandmother might try based on her preference or ingredients at hand. I also tweaked the potato salad, adding much higher amounts of the flavoring elements. I don’t think I’ve ever had a better one, and my own Zhbankov, photographer Erica MacLean, agreed.

The zefir was a Central Committee allocation in The Compromise, not a dish an ordinary person would make at home. I discovered that the sour taste of the marshmallow that befuddled me as a young woman was a green apple puree, whipped with an egg white and sugar to make marshmallow. (Green apple and chocolate? Go figure.) I did my best with a complicated multistep process that included tempering chocolate, sieving apple mash, and cooking a meringue base with hot syrup. The marshmallows didn’t quite set right, but I was pleased by how correct the finished zefir, and everything else, looked. If some of those items were all looks and no truth—well, they were inspired by a book about propaganda.

Marinated Mushrooms

1 pound mushrooms, any style, cleaned and trimmed

1 teaspoon salt for blanching the mushrooms

1 cup white vinegar

¾ cup water

2 cloves

2 bay leaves

3 black peppercorns

2 whole allspice

1 teaspoon sugar

1 tablespoon salt

1 clove garlic

Bring a large pot of water to boil, and add mushrooms and salt. Simmer for two minutes. Drain.

In a small saucepan, combine vinegar, water, cloves, bay leaves, peppercorns, allspice, sugar, and salt. Bring to a boil and turn off heat. Let cool.

Pour the marinade over the mushrooms. Cover tightly and refrigerate. Ready in three days.

Buterbrod

White bread, 1 loaf

Butter

Yellow cheese

Salmon Caviar

Slice the bread, slather it thickly with butter, top with cheese or caviar, and set out in a warm place to await the guests. Voila!

Potato Salad

2 large white potatoes

1 small beet

2 scallions, chopped

¼ cup black olives, chopped

2 tablespoons dill, finely minced

2 teaspoons tarragon, finely minced

¼ cup olive oil

½ teaspoon sugar

1 teaspoon salt, plus more to taste

Black pepper to taste

1 teaspoon white vinegar, plus more to taste

Bring two medium saucepans of water to a boil. Boil potatoes and beet, separately, until cooked through. Cool and peel.

Dice both potatoes and beet into quarter-inch cubes. Reserve beet. Place potatoes in a medium bowl, add all the rest of the ingredients, and taste to adjust seasoning. (I used a full extra teaspoon of white vinegar.) Mix in diced beet just before serving.

Kyiv-style Cutlets

1 pound ground beef

½ pound ground pork

½ cup milk

1 egg

1 tablespoon bread crumbs

1 tablespoon melted butter

1 teaspoon salt

Ground pepper to taste

1 cup riced potatoes (potato boiled and put through a ricer or food mill)

½ cup flour

Vegetable oil

2 cups chicken stock (Better Than Bouillon)

2 bay leaves

Place ground beef, ground pork, milk, egg, bread crumbs, melted butter, salt, pepper, and mashed potatoes in a large bowl and mix with your hands until well combined.

Place the half cup of flour on a plate, salt generously, and mix to distribute the salt. Set a bowl of water by your workspace. Shape the meat into oval-shaped cutlets, about the size of the palm of your hand, dipping your hands in water from time to time so the mixture doesn’t stick. Once the cutlets are shaped, roll each one in flour until lightly dusted.

Heat a generous amount of oil in a large skillet, add the cutlets, and fry until browned on all sides. Pour in the two cups of chicken stock, add the bay leaves, and bring to a boil. Cover and simmer for fifteen minutes.

Zefir

Adapted from the blog Sweet and Savory by Shinee. You will need a piping bag and large piping tips for cake decoration; Wilton 1M is recommended.

Puree:

7 ounces granny smith apples, peeled cubed

1 tablespoon sugar

Marshmallow:

1 egg white

¼ teaspoon salt

1½ cups sugar, divided

½ cup water

3 teaspoons agar agar powder

Chocolate dip:

1 11.5 ounce bag of Ghirardelli semisweet chocolate chips

1 tablespoon vegetable oil

Cook apples with one tablespoon sugar over medium-high heat for fifteen minutes, mashing as you go. You want the resulting paste to be fairly low in moisture content. Run the mixture through a sieve (you should have about two hundred and fifty grams of it), then cool and chill completely in the refrigerator.

Prepare your tools. Line two baking sheets with parchment paper, and mark with 2.5-inch rounds, using a pencil and shot glass. Spray the paper with cooking spray or grease with butter to prevent sticking. Set out the piping bag and tips you’ll be using.

Make the sugar syrup. In a medium saucepan, combine one cup of sugar, water, and agar agar powder. Stir once to combine, then cook over medium heat until the syrup reaches two hundred and forty degrees, or until it has started to turn color (if, like me, you don’t have a thermometer), about ten minutes. Tip: Don’t stir while the syrup is cooking.

While the syrup is cooking, make the meringue. In the bowl of your stand mixer, combine apple puree with egg white and salt. Beat the mixture on low speed until foamy and pale. Once the mixture is foamy, increase the speed to medium and begin adding the remaining half cup sugar, one tablespoon at a time, whipping until soft peaks form.

When the sugar syrup has reached the correct temperature, remove from the heat and let the bubbles subside, no more than thirty seconds. While the mixture is running on medium speed, slowly pour the sugar syrup into the meringue. Once all the syrup is in, increase the mixer speed to medium high and whip until stiff peaks form, three to five minutes.

Fill the piping bag and pipe immediately onto the prepared sheets, making 2.5-inch rounds. Set out to dry for eight to ten hours or overnight.

Once the meringue has set, fill a glass bowl with the chocolate chips and microwave for thirty seconds. Continue to microwave in ten-second increments, stirring between each one, until the chocolate is mostly melted and has only a few lumps left. Stir to completely dissolve lumps. Add the vegetable oil and stir again. Dip the marshmallows in the chocolate and return to the baking sheets to set. If the chocolate becomes too thick, return to the microwave for two ten-second increments, and continue dipping. Chocolate should be completely firm and ready to serve within an hour.

Valerie Stivers is a writer based in New York. Read earlier installments of Eat Your Words.

Copyright

© The Paris Review