Cooking with Nora Ephron

I am a baker of pies and a believer in pleasures, but also the kind of killjoy who can’t take a rom-com in the spirit it’s intended. Hence my fraught relationship with Heartburn by Nora Ephron. I remember—from 1983, the year the book was published—it being marketed as a “hilarious” comedy about a woman cooking her way out of a broken heart at the end of a marriage. Heartburn was a cultural sensation in the suburbs of my youth, such that I recall my mother cackling over the film adaptation and criticizing Meryl Streep’s looks—not pretty enough! The story was said to be inspired by Ephron’s divorce from Carl Bernstein and has always been considered a delicious revenge plot by a spurned woman upon a cheating man.

Ephron had a dazzling career as a trailblazer for women in journalism, and she wrote many of the greatest movies of all time, including When Harry Met Sally. She was a master, so my cavils over Heartburn‘s myths about romance will be brief: I don’t think a woman who stays in a bad relationship is just a starry-eyed believer in true love, as the heroine, Rachel Samstat, is presented to be. Nor do I think that men are just dogs—which is the book’s explanation for her husband, Mark Feldman’s, behavior—or that the happiest ending is finding a new relationship. But Ephron, in Heartburn, wasn’t looking to soul-search—this was her revenge novel. At one point, Rachel, who is a food columnist, admits to her therapist that she tells stories about her life in order to “control” the narrative. Ephron, writing Heartburn, was controlling the narrative of her divorce while showing off her wit, and she did it wonderfully. The one-liners never cease, as when Rachel says that Mark celebrates the political dysfunction of Washington, D.C., because if the city worked, “something might actually be accomplished and then we’d really be in bad shape” and adds, “This is a very clever way of being cynical, but never mind.”

Ephron describes linguine alla cecca as a “hot pasta with a cold tomato and basil sauce” that’s “so light and delicate that it’s almost like eating a salad.” Photograph by Erica MacLean.

Heartburn includes sixteen recipes integrated into the narrative and an index at the back listing their page numbers (a convenience I wish more novels included). Could the dishes be as good as the story? Some are daily staples, like bacon hash, the perfect vinaigrette, or a “four-minute egg.” Others Rachel perfects in her personal life or writes about in her column, such as peach pie and “Lillian Hellman’s pot roast.” The pièce de résistance, a key lime pie, has plot significance: when Rachel finally decides to leave Mark, she throws it in his face.

The food in the novel reflects a transitional time in American cuisine, when cooking from cans was still respectable but the from-scratch movement was in its embryonic stages. Julia Child and Craig Claiborne had already, in the sixties and seventies, introduced Americans to a greater number of international cuisines, and to higher standards. The Silver Palate Cookbook, published in 1982, suggested we might make sophisticated foods casually at home. Ephron’s Rachel reflects these changing times. She uses more canned ingredients than we would today and cooks simply, but her linguine alla cecca, sorrel soup, and homemade pies have ambition. I wondered, while recreating her recipes for this column, if her kind of eighties cooking might have been, counterintuitively, a pinnacle: classy yet easy. Rachel’s vinaigrette has three ingredients—Dijon mustard, red wine, and olive oil. If they’re perfectly balanced, do we ever need to think about vinaigrette again? Her cheesecake filling has four ingredients, and the recipe makes it simple enough to be thrown together on a weeknight: no bringing things to room temperature before combining; no stress-inducing water bath while baking. Such dishes seemed promising.

I hadn’t eaten a lima bean since my seventies childhood. The casserole, baked overnight in a low oven, did not have a pleasing scent. Photograph by Erica MacLean.

Others, like Lillian Hellman’s pot roast, which asks for “low-rent ingredients” like a can of cream of mushroom soup and a packet of dried French onion soup, seemed less so. There were also a few truly ominous outliers: a bread pudding calling for what seemed like too much of two powerful flavorings, nutmeg and vanilla; and a casserole of pears and lima beans from Rachel’s mother. This appalling dish is presented as an example of Rachel’s mother’s casual, irreverent attitude towards cooking, emblematic of her first-wave feminism, which Rachel, to some degree, reacts against. “My mother was a good recreational cook, but what she basically believed about cooking was that if you worked hard and prospered, someone else would do it for you,” Rachel says. She chooses a different path, one which does not include a pear-and-lima-bean casserole.

Because the recipes were so simple, I decided to try them all—with a small caveat—and thus provide the definitive word on the food in Heartburn. I’ve chosen the five best to reproduce below; anyone who wants the others need only buy a copy of the book. (The caveat was that there were three treatments for potatoes, grouped together in a single scene. I tried only one, and even better, I didn’t really have to try it, because Rachel’s method was identical to my own for making blissfully light and fluffy mashed potatoes.) The four-minute egg and the bacon hash were a morning’s breakfast. The outlier lima bean casserole required twelve hours in a two-hundred-degree oven, but even so, when I finally did the cooking, I made nine dishes in one day—in the time it usually takes me to make three or four. If I cooked like this every day, dinner would be more than fifty percent faster.

Ephron’s recipes were fabulous. Almost every dish was either the best version of its kind I’d ever made, or a fresh, simple take on a classic. Linguine alla cecca is a Sicilian cart-style pasta made with garlic-tomato-basil sauce—everyone should be doing this if they aren’t already. Cold, green, lemony sorrel soup has fallen out of favor, but it should come back. The bread pudding with “too much” vanilla and nutmeg was perfect and took about five minutes to assemble prior to baking. The cheesecake is a recipe from Rachel’s father’s second wife, of whom Rachel says, “Everything she made was the lightest, the flakiest, the tenderest, the creamiest, the whateverest.” Its method went against all my rules of cheesecake and its filling was lumpy-looking, liquidy, and thrown-together prior to baking—yet the results were indeed the lightest, tenderest, creamiest. The four-minute egg has become my new breakfast. The vinaigrette, so flavorful it doesn’t require salt, is my new vinaigrette. The key lime pie was tart, creamy, and classic. The peach pie asked that a custard be poured over the fresh peaches, a new technique for me. (I found it, in the end, too sweet.) The pot roast skipped the tedious flavor-developing steps of browning the meat and caramelizing the onions, instead using the two instant soups and a lot of red wine. Perhaps this was a sacrifice on health or on authenticity, but it didn’t affect taste.

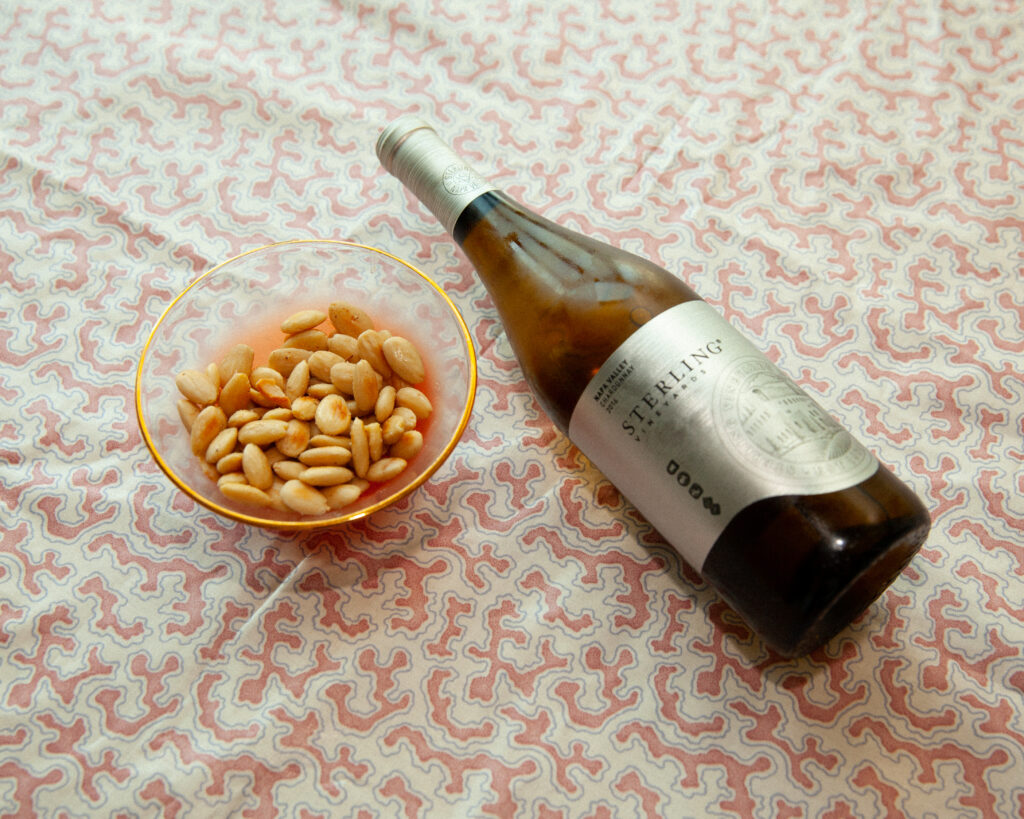

Sterling Vineyards makes a popular and conventional California chardonnay. Toasted almonds was another recipe from Rachel’s mother. Photograph by Erica MacLean.

The two off notes were the lima bean casserole, which I believe was meant as a humorous critique—I’ve never cooked anything that made my apartment smell so bad—and the wine. Rachel drinks a bottle of white wine before throwing the key lime pie in Mark’s face. My spirits consultant, Hank Zona, sourced me a bottle of California chardonnay from a popular mass-market producer still in existence from the eighties, which he thought would have been just the type to swill at a D.C. dinner party of the era. California chardonnays, then and now, are known for being tropical-fruity, oaky, crowd-pleasing, and heavy on mouthfeel. More sophisticated versions have become available and are even trendy, but they weren’t what we were looking for. I’d been surprised by the other eighties hits, so I tried my bottle with an open mind—but it was still not my preferred weight or flavor profile. Neither misstep could be said to be Ephron’s fault.

In the novel, Rachel sets up an opposition between being a career woman and having mastery over the domestic sphere of cooking and childcare. She chooses the latter and laments that as far as she can see, second-wave feminism has gotten women nothing but the “Dutch treat” date and double the workload. Ephron, however, was an overachiever extraordinaire who could write a revenge novel that would become a romantic comedy sensation and could cook perfectly, too. Whether this is realistic for most women remains a matter of debate, but for Ephron, bent on showing Bernstein what he was missing, it must have been a delicious conclusion.

All recipes reproduced from Heartburn.

Key Lime Pie

First you line a 9-inch pie plate with a graham cracker crust. Then beat 6 egg yolks. Add 1 cup lime juice (even bottled lime juice will do), two 14-ounce cans sweetened condensed milk, and 1 tablespoon grated lime rind. Pour into the pie shell and freeze. Remove from the freezer and spread with whipped cream. Let sit five minutes before serving.

Linguine alla Cecca

Drop 5 large tomatoes into boiling water for one full minute. Peel and seed and chop. Put into a large bowl with ½ cup olive oil, a garlic clove sliced in two, 1 cup chopped fresh basil leaves, salt and hot red pepper flakes. Let sit for a couple of hours, then remove the garlic. Boil one pound of linguine, drain and toss with the cold tomato mixture. Serve immediately.

Peach Pie

Put 1 ¼ cups flour, ½ teaspoon salt, ½ cup butter and 2 tablespoons sour cream into a Cuisinart and blend until they form a ball. Pat out into a buttered pie tin, and bake 10 minutes at 425°. Beat 3 egg yolks slightly and combine with 1 cup sugar, 2 tablespoons flour and ⅓ cup sour cream. Pour over 3 peeled, sliced peaches arranged in the crust. Cover with foil. Reduce the oven to 350° and bake 35 minutes. Remove the foil and bake 10 minutes more, or until the filling is set.

Pot Roast, Lillian Hellman’s

You take a nice 4-pound piece of beef, the more expensive the better, and put it into a good pot with 1 can of cream of mushroom soup, an envelope of dried onion soup, 1 large chopped onion, 3 cloves chopped garlic, 2 cups red wine and 2 cups water. Add a crushed bay leaf and 1 teaspoon each thyme and basil. Cover and bake in a 350° oven until tender, 3 ½ hours or so.

Valerie Stivers is a writer based in New York. Read earlier installments of Eat Your Words.

Copyright

© The Paris Review