Cooking with Dante Alighieri

For the past fourteen months I have been on a path of conversion to Catholicism. In addition to going to mass, trying to memorize prayers, and worrying about my singing voice, I attend a staid biweekly discussion group moderated by a priest. We are slowly reading a book of contemporary Italian theology. My conversion was spurred by a specific—and specifically Catholic—experience of grace. I am confident about it, but less so about reconciling myself with the many dogmas of Catholic Church. I have struggled especially, as a previously secular person, with believing in sin. As a category, it has always seemed socially malignant, an excuse to burn witches. And in my personal life both gluttony and lust might be problems, especially because they don’t really seem like problems: sex and food are good things.

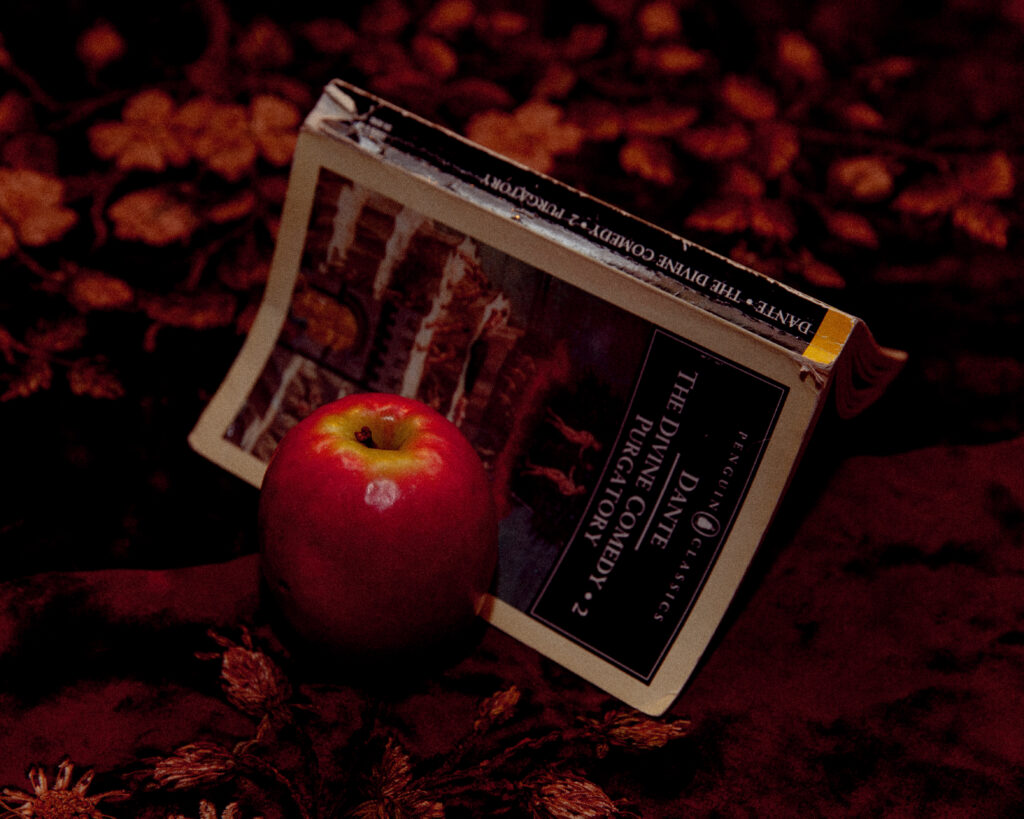

“The ideal way of reading The Divine Comedy would be to start at the first line and go straight through to the end, surrendering to the vigor of the story-telling,” writes translator Dorothy Sayers. Photograph by Erica MacLean.

And so I was overjoyed to find an articulation of sin that makes sense to me in The Divine Comedy, by Dante Alighieri (1265-1321), a three-volume work wherein a pilgrim travels through nine circles of hell and then seven cornices of purgatory, before reaching paradise. The version I’m reading was translated and annotated by English mystery writer Dorothy Sayers, who was also a theologian, and I found her work on natural and moral law, laid out in the book The Mind of the Maker, helpful as background to understanding Dante. Natural laws, Sayers wrote, are “statements of observed facts inherent in the nature of the universe”—along the lines of “if you hold your finger in the fire it will be burnt.” The religious viewpoint says there is also a “universal moral law,” which is itself a natural law, “which consists of certain statements of fact about the nature of man.” By behaving in conformity with moral law, “man enjoys his true freedom”—a state available in this life, which we might call happiness, or a kind of soul-deep fulfillment. Behavior that does not conform with the moral law “tends to enslave mankind and produce the catastrophes called ‘judgements of God,’” Sayers says. Sin, then, is behavior that does not conform with moral law; behavior which is spiritually and soulfully bad for us and will hurt ourselves and others. Injunctions on sin do not exist to deny us pleasures but to save us from harm.

The pleasures that landed a French pope in purgatory: fried eels and sweet Vernaccia wine. Red Vernaccia Nera bubbles sourced for me by spirits consultant Hank Zona. Photograph by Erica MacLean.

Viewed through this lens, The Divine Comedy becomes the page-tuner Sayers claims it is, offering “the drama of the soul’s choice” in this life. And while my general-secularist understanding of sin has been that it condemns activities that really aren’t bad at all, what I found in the lowest rings of The Inferno were behaviors that did seem like our human worst. In the last trench of circle eight, for example, alchemists are punished. These are “transmuters of metals,” as Sayers puts it, “every kind of deceiver who tampers with the basic commodities by which society lives.” Dante indicates that their behavior breaks “the general bond of love and nature’s tie” between people—almost the worst thing you can do. I imagine today’s alchemists as makers of poison baby formula or builders of shoddy public housing; circle eight, trench ten is just what they deserve. Just below them are three giants whom Sayers believes are “images of the blind forces which remain in the soul and in society” when the general bond of love is withdrawn. The giants are “blocks of primitive mass emotion” representing “nonsense,” “senseless rage,” and “brainless vanity.” Reading this, I thought about the contemporary internet and especially the impacts of social media—which seems to me located between rings eight and nine of hell.

An Italian preparation of eels asks for a marinade of garlic and bay leaves. For more authenticity, substitute a white Vernaccia wine for the vinegar in the recipe. Photograph by Erica MacLean.

In this moral universe, my own sins of lust and gluttony turn out to be the least bad sins, punished in the first two circles of hell and purged on the last two cornices of purgatory. Both my vices are what Sayers calls sins of “incontinence” produced by “self-indulgence, weakness of will and easy yielding to appetite.” Their mitigating factors, according to Dante: they are not related to desire to do harm; they often concern pleasure and mutuality. But there are ways in which these behaviors often just don’t work for us. Punishments throughout the Divine Comedy are “simply the sin itself, experienced without illusion,” Sayers writes. What unrepentant sinners did in life, they will do forever in hell, without the illusion that the sin was pleasurable.

In hell, for example, the lustful are swept along by a black wind. “The bright, voluptuous sin is now seen as it is—a howling darkness of helpless discomfort,” Sayers says. This helpless discomfort is of course not located in all forms of sexuality—but I know it can be found there. And gluttony, a sin which begins in mutual indulgence, leads, according to Sayers, by “imperceptible degradation to solitary self-indulgence.” I’d understand that to mean that it’s not the dinner and drinks with friends that are the problem but the binge-eating afterwards. And if we take the lessons of The Divine Comedy seriously, perhaps one leads to the other more than we realize. The gluttonous in Canto VI wallow in the mud, being torn by the claws of Cerberus, an experience Sayers calls “a cold sensuality, a sodden and filthy spiritual wretchedness.” This description dovetails with my experiences of binge-eating—enjoyment of food gone too far.

Equally important, Dante’s gluttonous are responsible for “prey[ing] on people and things,” Sayers says, a concept that relates to our increasing awareness of food systems and food ethics. If your consumption preyed upon others in life, in hell you are turned into the prey of a three-headed dog. In purgatory, the punishment for gluttony is starvation—a fate which also seems illuminating when we think in the network of global consumption. I turned to this concept, with Purgatory as my guide, in order to cook from Dante. Dante describes the this fate in Cantos XXII-XXIV; the emaciated shades of the gluttonous are teased by a tree “green with laden boughs” whose “crop of tempting fruit ambrosial odours spread.” The tree tapers from bottom to top, so the shades cannot reach its fruit, and it is cascaded with spray at the top from a mountain stream, also out of reach of the thirsty sinners. Beneath the tree we meet people who ate and drank too much. One is a Frenchman named Simon de Brie, who died from a surfeit of “Bolsena eels and sweet Vernaccia wine.” Another is Ubaldin dalla Pila, “a liberal and cultivated man, with a great knack for inventing new culinary recipes,” as Sayers explains in a note. (As an inventor of recipes, I am concerned!) In contrast with these peoples’ behaviors, Dante celebrates a “primal age … beautiful as gold” when “Hunger made acorns savory to its need” and “Streams for its thirst like rills of nectar rolled.”

“Gluttony tends to be, on the whole, a warm-hearted and companionable sin,” Sayers wrote. I served the scones made from these acorns to as many friends as possible. Photography by Erica MacLean.

I decided to make a combination of gluttonous and virtuous foods: I’d serve “bad” Italian-style fried eel with Vernaccia wine, but would also make “good” scones with tree fruit and acorns. And a third dish would be a mixture of bad and good: an apple, taken straight from the tree of the knowledge (and my favorite fruit, incidentally), sweetened virtuously with honey. Dante remarks that “locusts and honey were enough to feed / The Baptist in the desert.” The usage of acorns seemed especially appropriate to counteract gluttony, since I have tried to make acorn flour before and discovered that processing acorns is so time-consuming, finicky and laborious that the results must be energy-negative. Acorns are also the kind of foraged and wild-crafted food recommended for a more sustainable lifestyle (though humans should harvest them only in years when they are bountiful in order not to negatively impact squirrel populations).

I had acorns in my freezer from a previous adventure cooking from the work of Mary Shelley and began working on them about a month in advance; there was no easy gluttony in this task. Acorns are bitter and very tannic, and their interior meat is encased in a tightly fitting husk that might be poisonous (sources conflict). I tried various methods recommended online to remove the husk, including boiling the acorns, which didn’t work, and shaving it off with a knife, which did, but was incredibly slow. Since I was doing penance for my sins, I dutifully shaved acorns in my free time for about a week before discovering, mostly by accident, that the husk falls right off previously frozen acorns cracked and left out on the counter to dry for a few days. Leaving the acorns exposed to the air makes the outer flesh oxidize and turn black, but it didn’t seem to affect the color of the final flour. In fact, my final flour was lighter in color than that of the commercial kind I’ve bought before.

Once the acorns were peeled, I had to leach out their tannins, a process that can take between three days and two weeks depending on the type of acorn. I ground my acorns with water in the blender, making a mixture that looked like a coffee milkshake, and then placed it in a large jar in the refrigerator. Once the mixture settled, I began pouring off the water and refreshing it twice a day. Internet sources instructed me to preserve the white layer on top of the flour, allegedly the fat and starch, by straining the mixture through cheesecloth with every refresh. I tried, but my cloth was too porous and my fat and starch layer was lost—perhaps better from the standpoint of gluttony. At first, the mixture was overpoweringly oaky and bitter and smelled strongly of vanilla; but as promised, after two weeks of assiduous leaching, it became bland and pleasant with an oaty, milky scent. At that point I drained it and spread it out on a cutting board, fluffing and stirring it with my fingers every day or two until it dried. This might take a few days in a warm climate, but for me it took a week. I then ground it again (by the three-quarters cup in a coffee grinder—also a slow task) and set out to bake the world’s most hard-earned scone, using a recipe I’d previously had success with using commercial acorn flour, and substituting dried figs, a classic Italian ingredient, for the foraged dried apples I’d previously used.

My three dishes were some of the ugliest food I’ve ever made—which made me happy morally, if not creatively. To see ugly truths behind illusions is, I think, the first steps toward the kind of spiritual self-improvement I’m seeking. I thought the unaesthetic results might also reveal my sins from a new angle. I propagate photos of pretty foodstuffs on the internet—which I have located between circles eight and nine, don’t forget—a practice that encourages appetite in others and supports a lazy subconscious assumption that our food is all pretty and good. Yet we know the stories behind it are often ugly.

In terms of taste, my dishes fell neatly into the categories of bad, mixed, and good, almost as if Dante had placed them there. I have never had much success cooking eel. When cooked well, it is tender and melting, but mine always turns out tough. Neither the texture nor the oily, fishy flavor would tempt anyone to overconsume. The baked apple was fine, a reliable dish of moderate sweetness. I ate it but thought it really could have used some ice cream. (Would this have been a sin?) And the homemade acorn flour scones were incredible, and even grew on me as I polished them off over several days. The flour had a sweet, nutty, faintly oaky flavor, and a unique brawny toothsomeness. Its relative lack of fat and starch made the scones crisp-dry on the outside and perfectly pillowy in the center. I’ve since made a second version without figs and with pecans, which was even better, and the recipe below reflects the changes. The virtue of restraint, in this case, really was its own reward.

The wine for my meal was a Vernaccia, a type which appears frequently in medieval and early Renaissance Italian literature. My spirits consultant Hank Zona explained that in that time period, it was a lightly macerated sweet wine that could have been made from any number of grapes. Today the term refers to wine made from a specific Vernaccia grape, of which there are several. Hank chose a bubbly red Vernaccia Nera from Italian producer Paris Rocchi, a second-generation vineyard run by a brother-sister team. He said that bubbles and fried food go well together, and that the eel’s meaty flesh would pair with the earthy, dark-berry notes in the wine. The wine went a long way towards improving the dish, and unlike the other sinful food, was delicious.

I enjoyed drinking the wine and pulling together the meal, odd as it may have been. Despite the complexities, I hope such enjoyment is not a sin—but I suppose, someday, I’ll find out.

Fried Eel

½ pound eel fillets

2 cloves garlic, smashed

3 bay leaves, crumbled

Salt

Pepper

Olive oil

1 tablespoon champagne vinegar

⅓ cup flour, for dredging

Light flavorless oil for frying

Lemon wedges to serve

Chop the eel fillets in three-inch pieces. Set them in a flat-bottomed dish, topped with garlic and bay leaves. Season with salt and pepper, drizzle with olive oil and vinegar, and set aside to marinade for at least an hour or ideally overnight. When you’re ready to cook, place the flour in a shallow dish, season with salt and pepper, and dredge the eel pieces. Heat the oil in a large skillet to approximately 350 degrees and fry the eel until browned and crispy, being careful not to crowd the pan. Set on paper towels to drain and serve with lemon wedges.

Acorn Scones

For the acorn flour:

1 gallon freezer bag filled with acorns.

For the scones:

1 cup white flour

¾ cup acorn flour

1 tablespoon baking powder

¼ cup sugar

¾ teaspoon salt

8 tablespoons cold unsalted butter, diced

⅓ cup pecans, chopped

3 tablespoons buttermilk

1 egg

To make the acorn flour:

Pre-freeze your acorns for at least a day. Remove from the freezer, crack the shells, and spread them out on a countertop to dry for two or more days, waiting until the inner husk of the acorn falls off easily. The acorn flesh will turn black, but don’t worry about it. When you can easily remove the husks, do so, then process the acorns in your blender in batches, using about a 1:2 ratio of acorns to water. Put the resulting mixture in a large jar with a lid, refrigerate, and wait for the flour to settle to the bottom. When it has, you can pour off the top of the liquid, add more water, shake and repeat. Refresh the water in this way twice daily until the tannins have leached out and the flour is bland and pleasant to taste, anywhere from three days to two weeks. If you are not sure if the flour is bland enough, give it more time. When ready, drain and spread out in a warm place to dry on a large baking sheet, anywhere from one day to one week. At this point you’ll have a chunky, polenta-like meal. Grind again in a coffee grinder until fine. One gallon freezer bag of acorns produces about three cups of flour.

To make the scones:

Preheat the oven to 375. Mix together the acorn flour, white flour, baking powder, sugar, and salt in a medium mixing bowl. Add the cold butter and cut in with a pastry blender until the mixture is mostly combined and any remaining chunks of butter are smaller than pea-size. Add the pecans and stir. Make a well in the center and add the egg and the buttermilk. Whip with a fork to combine, and then start pulling in the flour mixture, stirring until the entire mass is moistened. Use your hands to crunch the dough together until it is homogenous and forms a single ball. Place the dough on a baking sheet, flatten slightly with a rolling pin, and cut it into six wedges. Pull the wedges apart a little so they don’t stick together when they cook. Bake for sixteen minutes, until puffy and cooked through.

1 apple

2 teaspoons honey

1 teaspoon chopped pecans

Preheat the oven to 350. Cut the cap off the apple and remove the core. Fill with the honey and pecans, place in your smallest baking dish, cover the dish with foil, and bake for thirty to forty-five minutes, until the apple is soft.

Valerie Stivers is a writer based in New York. Read earlier installments of Eat Your Words.

Copyright

© The Paris Review