Cooking with Cyrano de Bergerac

In the opening scene of the play Cyrano de Bergerac by Edmond Rostand, first performed in 1897, “orange girls” at a Parisian theater in the 1640s make their way through an audience of soldiers, society ladies, noblemen, and riffraff, selling orangeade, raspberry cordial, syllabub, macarons, lemonade, iced buns, and cream puffs. The handsome soldier Christian de Neuvillette and his friends sample their wares, drink wine, and eat from a buffet. A poet and pastry cook named Ragueneau banter-barters an apple tartlet for a verse. Then the poet and militia captain Cyrano arrives, and in a glorious, idealistic act, spends his year’s salary to get a bad actor kicked off the stage. The orange girls offer the hungry man nourishment, but he eats only a grape and half a macaron, staying to true to a kind of restraint that defines his character. Food, in other words, plays a major role in the play—one that culminates in act 4, when Roxane, the woman both Christian and Cyrano love, arrives at the Arras front in a carriage stuffed with a feast for the starving soldiers: truffled peacock, a haunch of venison, ortolans, copious desserts, ruby-red and topaz-yellow wine.

Jewel-like candied fruit decorates a pastry lyre whose “strings are all spun sugar” at Ragueneau’s shop. Photograph by Erica MacLean.

I’ve seen three versions of Cyrano this year—a 2021 movie starring Peter Dinklage, with an original score by the band the National; a staging of the play at the Brooklyn Academy of Music, starring James McAvoy; and the 1987 Steve Martin movie—and in none of them did I pick up on a food theme. Its absence, I thought, must mean something.

The original Cyrano de Bergerac was a period piece, set in 1640 but written in 1897 by a successful Paris playwright who has fallen into obscurity in our time. (I found only a single academic biography on Rostand, though his mustache alone deserves a tome.) The plot is a love triangle. Cyrano loves Roxane, but he believes she cannot return his love because of his huge nose. Roxane has a crush on Christian, because of his pretty face. Christian, tongue-tied and insecure, can’t provide Roxane with the intellectual stimulation she seeks, so he allows Cyrano to write letters to her, signing them as Christian. Roxane falls madly in love—but with which man? It’s a perfect romantic comedy that taps into universal themes. Anyone can identify with the lover’s fear that they cannot be loved due to a fatal flaw, physical or otherwise. But its influence on Parisian society in the late nineteenth century was highly specific.

Cyrano de Bergerac was a celebration of French culture, so my spirits consultant, Hank Zona, supplied me with three French wines, two aged whites from Jura, and one red from Bergerac. Photograph by Erica MacLean.

At the time in France, religious participation was waning and the national spirit was depressed by a loss in the Prussian War. Cultural achievements like the great works of Racine, set in Alexandrine verse, seemed a thing of the past. Rostand seized this old form in order to advocate a “return” to an idealized past whose values were chivalry and romance, military prowess and bravado, wit and culture. French decline could be reversed, he suggested, with bold individuality and Cyrano-like panache. (That word literally meant the plume on a musketeer’s hat until Rostand transformed it into a national virtue.)

As the plot develops, Cyrano chooses artistic integrity over patronage, and he throws himself into battles that he cannot win. As a lover, he sacrifices everything, and he wins Roxane’s heart only on his deathbed. By today’s standards, it’s a tragedy—we believe talent should be rewarded, soldiers shouldn’t be sent on foolish missions, and that one-sided relationships are delusional. But Rostand intended Cyrano’s fate as a triumph: he sticks to his ideals. To a nation with no real-world victories to celebrate, this concept of a victory achieved through spirit and attitude was powerful and moving.

Sweets meet meat at Ragueneau’s pastry shop. He has geese, ducks, peacocks, and a chandelier hung with carcasses of game. I had a roast beef. Photograph by Erica MacLean.

The message found its audience and the play was a sensation, becoming not just the most successful play of its time but one of the most successful plays of any time, according to an introduction by the translator Carol Clark in my Penguin Classics edition. Songs were written, audiences learned passages by heart, plates and ashtrays with huge noses on them were produced. On the hundredth night of the original run in 1897, the supporting cast from Ragueneau’s pastry shop walked out into the audience, handing out cream puffs. The effect on French society was such that Clark speculates that the French victory a few decades later in World War I could in part be attributed to ongoing Cyrano mania, as French soldiers took him as a role model when facing overwhelming odds.

Every detail matters for the notoriously challenging French macaron: add the food dye to the meringue base before folding in the solids. Photograph by Erica MacLean.

This emphasis on idealism, I believe, is reflected by Rostand’s depictions of food, which are far from realistic. The menu, with its decadence and its exotic game meats, played on 1890s stereotypes about the 1640s, and was a historical fiction referencing a previous work of historical fiction, The Three Musketeers by Alexandre Dumas. Audiences were not intended to take it seriously. In act 2, “The Poet’s Cook Shop,” Rostand’s lengthy stage directions describe roasts “already weeping into the dripping pans” and assistants with chicken wings stuck into their hats. The gathered poets call out as desserts whirl by, naming cream buns, macarons, and even “a lyre! In pastry! Stuck with candied fruits!” Ragueneau declaims a full recipe for almond tartlets in verse. “Mm-mm! Delicious! Exquisite! Divine!” cry the poets, their mouths full of the tarts. With food this deliberately farcical and overblown, Roxane can drive her implausible carriage through enemy lines to a battlefront without eliciting an eye roll. It’s better, in fact, that the feast she brings is ridiculous, because the true feast for the soldiers on the eve of their deaths is self-sacrifice, patriotism, spirit, panache.

More meringue technique: ideally, you pipe the batter into “mounds” in the center of your circles, since it will spread. Photograph by Erica MacLean.

In modern versions of the play, the lavish spreads disappear, I suspect because we live in a more pragmatic society; ideals, we think, should be linked to the possible, and in most cases we’re busy trying to make them a reality. For us, intangible victories like Cyrano’s are hardly worth celebrating—and so the contemporary version of Cyrano is brought down to earth. The Steve Martin movie, for example, dispenses with the chivalric ideal of unrequited, unconsummated love, and pastes on a mundane ending in which Cyrano and Roxane end up together. The 2021 Cyrano goes a step further and interprets the hero’s acts of principle and his grand gestures as futile. Cyrano’s unwillingness to speak of his love to Roxane becomes emblematic of his pride and insecurity, and his ending is simply a tragedy. In this version, the scene where Roxane shows up at the front disappears, and a single withered apple stands in for all the venison and ortolan. It’s a more realistic representation of the food you might find on a battlefield, but it’s not Cyrano de Bergerac. Something similar happens in the version I saw at the Brooklyn Academy of Music, an adaptation written by the playwright Martin Crimp that turns Cyrano’s story, very effectively, into one about toxic masculinity. Chivalry and bravado restrict Cyrano rather than liberating him; he dies with his last word still trapped on his lips. Roxane appears at the front, and she brings a lemon tart that’s a riff on Ragueneau’s rhymed tart recipe, but she also brings necessities like bread and water. It’s practical, but it’s not a menu to celebrate a triumph of the spirit.

The rhyming recipe was silent on the form the almonds should take. I chopped mine. Photograph by Erica MacLean.

I chose to make the feast of the spirit, as Rostrand intended, and immediately encountered the high price of enacting the ideal. French wine is not cheap, and the characters drink it throughout Cyrano de Bergerac. Burgundy and bordeaux are named in the script. My wine consultant, Hank Zona, found me a bottle of Vigne d’Albert from Famille de Conti, a winemaker in Bergerac (which may not have been where the historical poet Cyrano de Bergerac was from, but the play is already ahistorical). The region is sixty miles west of Bordeaux, and makes wines with similar grapes. Hank speculated that the bottle’s inclusion of humble, historical field grapes, plus its low-intervention production methods, make it similar to what they would have been drinking in either the 1640s or the late 1800s, take your pick. For a “topaz-yellow” wine, he suggested a vin jaune, an aged white wine which is a specialty of the Jura region in France; aging creates a richer, more amber color. True vins jaunes start at seventy-five dollars a bottle, so he found me two aged whites from Jura that were more reasonably priced, one of which used Savagnin, the grape used in vin jaune.

A bottle of aged Chardonnay from Domaine Overnoy-Crinquand had the amber color I was looking for and tasted of apple peel, brioche, walnut, and gray stone. Photograph by Erica MacLean.

I wanted a haunch of venison to pair with my full-bodied wines, and I sought out a particular bone-in cut that looked suitably dramatic and seemed like what the soldiers might have gnawed on during the scene with Roxane. Unfortunately, supply-chain shortages have affected the venison market (who knew?), and the only cut available to me through my butcher was seven pounds, came in several different muscle bundles, had to be tied and cooked correctly, and would have cost $150. In an attempt to save money, I pivoted to making a roast beef from Ragueneau’s, and then discovered during the research process that the secret to perfect roast beef is a truly accurate meat thermometer, and buying one evaporated the savings. More outlay went toward superfine almond flour and superfine sugar to make French macarons, trial runs of tartlets stuffed with expensive almonds—many trial runs are necessary when you’re developing a recipe from a rhyme, candied fruit from Kalustyan’s, and the seven boxes of frozen puff pastry I used up learning how to make a lyre. Cyrano could dine on air for his art; I would be dining on rice and beans for a month after this blowout.

My final menu consisted of a roast beef, almond tartlets, raspberry macarons, and the pastry lyre studded with candied fruit. I made the beef from a friend’s extremely simple recipe. You drench it in salt and pepper, brown it, bake in a 250-degree oven for under an hour until it reaches a particular temperature, then raise the heat to finish it off. My new thermometer revealed that my oven cooks even hotter than I realized, but now that I knew that, I could make the recipe correctly. The pastries presented more serious problems—Ragueneau had a whole patisserie stocked with assistants, ones who wore chicken wings in their hats, no less. I had a rhyming recipe for almond tartlets that came with some suspicious instructions, such as soaking the almonds in milk until “soft as silk” and beating eggs for the filling until “light as air.” (Neither technique is a modern preparation for an almond tart, and neither were good on trial runs.) I also had to make macarons, a notoriously finicky cookie that won’t form its trademark ruffled “feet” if any of the steps go wrong. For the pastry lyre there was simply no model or recipe available at all. I started with the basics: I googled “lyre” and wondered what kind of pastry to use.

I drew a model for a lyre freehand, based on a photo, and then cut it out of frozen puff pastry. Photograph by Erica MacLean.

My finished tartlets were dry, but better than those more faithful to the rhyme. (I ended up with a conventional filling of almonds, eggs, and heavy cream, which I lightened up some with whipped egg whites.) My macarons were oversized and messy, but miraculously they had the proper crinkling around the base, which show you got the batter right. For the feather in my musketeer’s cap, the pastry lyre, I decided to buy frozen puff pastry dough, stuff it with an easy and conventional Danish filling of cream cheese and jam, and then focus my creative efforts on shaping it. Braiding and twisting techniques were fun and created my household’s new favorite breakfast, but they didn’t produce a pastry that could be attractively decorated. Eventually I cut the shape out flat and arranged fruit on top, creating what I thought was a very impressive-looking finished product. It may not have been historically accurate—it may have even been a little undercooked in places where the fruit was sitting—but like my own preferred Cyrano, it had panache.

Roast Beef

Required accessory: a meat thermometer.

1 boneless beef roast, 3-4 lbs, tied and at room temperature

salt

pepper

1 tbsp neutral oil

Adjust the oven rack to the lower-middle position, and preheat the oven to 250 degrees. Heavily salt and pepper the beef on all sides. Heat the oil on medium-high heat in a medium-size cast-iron skillet until hot. Sear the beef on all sides, about two minutes a side.

Place the skillet in the oven and cook until the temperature reaches 110 on an instant-read thermometer, about forty minutes to one hour. (Start checking at thirty minutes.) Increase the oven temperature to 500 and cook until the internal temperature reaches 120 for rare, 125 for medium-rare, or 130 for medium, about ten to twenty minutes longer. (Cooking times can vary, so start checking at five minutes.) Remove from the skillet and transfer meat to a cutting board. Tent the roast with foil and let stand for twenty minutes. Snip the twine off the roast, cut it into thin slices, and serve.

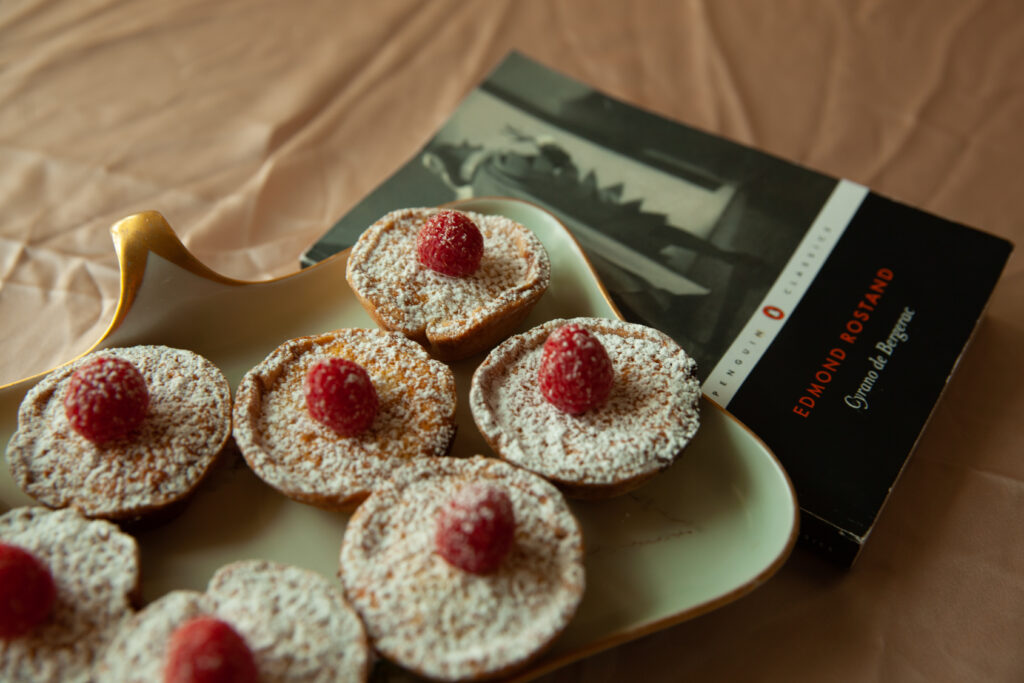

Almond Tartlets

The following rhyming recipe appears in Cyrano de Bergerac.

First for the filling almonds soaked in milk,

As soft as silk

Add them to eggs beaten light as air

And waiting there

Cut up your short crust and put it in

A tartlet tin

Press down each dainty round and neatly pour

A spoon or more

Of almond mixture in each waiting nest

Don’t let them rest

But quickly to the oven bear the tray

There it must stay

For fifteen minutes. Then, like burnished gold

Lo and behold

For the crust:

1 3/4 cup flour

1 tbsp sugar

1/4 tsp salt

1 tsp lemon zest

1/2 cup cold unsalted butter

1 egg

1 tbsp water

For the filling:

1 egg, yolk and white separated

1/2 cup sliced almonds

1/4 tsp vanilla extract

1/4 tsp almond extract

1/4 cup heavy cream

2 tbsp sugar

pinch of salt

12 raspberries

powdered sugar to serve

Combine flour, sugar, salt, and lemon zest in a large bowl. Cut the butter into cubes, then cut in to the flour using a pastry blender. (Some people do this in a food processor.) Pinch with your fingers until the butter is combined and the mixture is the consistency of rough cornmeal. Whisk the egg with the tablespoon of water in a small bowl, then add this to the flour-butter mixture. Stir until combined, then crunch gently with your hands until the dough comes together.

Immediately roll out the dough between two sheets of wax paper or parchment paper, until it is very thin, ideally less than a quarter inch. Place in the refrigerator for twenty minutes to chill.

Preheat the oven to 375 degree. Gather your materials: a twelve-cup muffin tin, a three-inch round cookie cutter, pie weights, scissors. When the dough has chilled, cut it into twelve three-inch rounds. Push each round gently into the muffin cups. Cut a sheet of the parchment you used for rolling out the dough into four-inch squares, and press a square neatly against each tartlet cup. Fill with pie weights and bake for fifteen minutes. Remove and let cool.

Whip the egg white until stiff and “light as air.” Combine all the other ingredients in a medium bowl and stir to combine. Fold in the whipped egg white. Fill each cooled tartlet cup with filling, about one tablespoon. Return to the oven and bake for fifteen minutes, until the filling is set and the tarts look “like burnished gold, lo and behold.” Let cool. Top with a raspberry, dust with powdered sugar, and serve.

Raspberry Macarons

Adapted from Sally’s Baking Addiction.

For the macarons:

100g egg whites, pre-separated and aged for 24 hours in the refrigerator

1/4 tsp cream of tartar

1/2 tsp vanilla

80g superfine sugar

1–2 drops gel food coloring

125g superfine almond flour

125g confectioners’ sugar

For the raspberry filling:

3 tbsp unsalted butter, at room temperature

1 cup powdered sugar

1/4 tsp vanilla

1/4 tsp lemon juice

small pinch of salt

2 tbsp ground freeze-dried raspberries

Line two baking sheets with silicone baking mats or parchment paper. If using parchment, mark the sheets with one-and-a-half-inch circles, set about two inches apart, and then flip the paper. This will serve as a guide when it’s time to pipe the macarons.

Add cream of tartar and vanilla extract to the egg whites. Beat on medium speed in a stand mixer fitted with a whisk attachment until very soft peaks form. You do not want to overbeat. Stop as soon as the beater leaves tracks in the foamy egg whites. Add one third of the sugar, beat for five seconds, then, with the mixer continuing to run, add one third more of the sugar. Beat for five more seconds and add the rest of the sugar. Continue to beat on medium-high speed until stiff, glossy peaks form. Add the food coloring and fold in with a rubber spatula until combined.

Sift the almond flour and confectioners’ sugar together in a large glass or metal mixing bowl. Use a spoon to force any larger lumps through the sieve. (You don’t want to leave much behind or you won’t have enough of the dry ingredients for the finished batter.) Slowly fold the beaten egg whites into the almond flour mixture in three additions. After you add all the egg whites, play very close attention to the consistency of your batter. Continue folding the batter, which deflates air, until it reaches the “macaronage” stage. It should drizzle slowly off the spatula like honey. If you make the form of a figure eight, it should take no more than ten seconds to sink back into itself.

Spoon the mixture into a piping bag. Pipe into mounds slightly smaller than your marked circles, since the batter will spread. Drop the baking sheets onto the counter a few times to bring any air bubbles to the surface. Pop the air bubbles with a toothpick. Leave the piped cookies to set for thirty minutes to an hour, until the tops have dried slightly. Don’t leave them longer than that or they might begin to deflate.

Meanwhile, preheat the oven to 325 degrees. When the tops of the macarons have set, bake for thirteen minutes. As they bake they should form feet. To test for doneness, lightly touch the top of the macaron with your finger. If it seems wobbly, it’s not done and needs one or two more minutes. When it seems set, it’s done. Set aside to cool.

Make the filling. Combine butter, powdered sugar, lemon juice, vanilla, and salt in the bowl of your stand mixer, fitted with the whisk attachment. Starting on medium-low, whisk until the ingredients are combined. Scrape down the sides, turn the speed up to medium-high and beat until fluffy. Add the powdered raspberries and mix until combined. Fill a piping bag with the frosting.

When the macarons are cool they should lift right off the parchment. Pipe half the cookies with raspberry filling, and use the other half to make “sandwiches.”

A Pastry Lyre Studded with Candied Fruit

Required accessories: a piece of paper cut out in the shape of a lyre, to use as a pattern.

1 box frozen puff pastry

4 oz cream cheese, preferably at room temperature

1 egg, yolk and white separated

3 tbsp sugar

1/2 tsp lemon juice

1/2 tsp vanilla extract

strawberry jam

candied fruit for decoration

Preheat the oven to 400 degrees. Remove your puff pastry from the freezer and set both sheets on the counter to thaw just to the point that they can be unfolded without breaking. (If the dough gets too soft, it will be difficult to handle.)

In the meantime, make the cream cheese filling. Combine cream cheese, egg yolk, sugar, lemon juice, and vanilla in a small bowl. If the cream cheese is cold, the filling with be lumpy, but this won’t matter once it’s baked.

Dust the countertop with flour, unfold one of the sheets of puff pastry, and place the lyre-pattern model on top. Cut out using a sharp knife. Transfer to the baking sheet and repeat the cutting-out process with the second sheet of puff pastry. Working quickly, so the dough does not warm up too much, spread the base of the lyre (the one on the baking sheet) with cream cheese filling (you won’t use all of it). Top the filling with dollops of strawberry jam. Place the second lyre on top of the filling.

Make an egg wash by adding one tablespoon of water to the egg white and whisking with a fork until combined. Brush the top of the pastry with egg wash. Decorate with candied fruit and bake for eighteen to twenty-two minutes, until the pastry is puffy and golden brown.

Valerie Stivers is a writer based in New York. Read earlier installments of Eat Your Words.

Copyright

© The Paris Review