C’est la Vie!: A French Cancer Diary

Margot Bergman, Untitled (Cup), 1985–1992, from a portfolio in issue no. 244.

July 20

After a day of spewing blood, I am in a French hospital.

Since I’ve never been sick in my life, I had no comprehension of how serious it is to puke red. By the afternoon, I’d lost so much blood my skin changed color and I couldn’t stand up or feel my hands. I was in the bathroom and my phone was in the bedroom and I couldn’t even crawl to it. I thought I was going to die there. I was thinking mainly of the book I want to finish, which is probably vain or inhumane, but that’s me. I did think of my daughter Sadie, who has really been kicked around by life in the three years since high school, but I have confidence that she will work it all out—she has a core that’s solid and true. I also thought of Bruno, my groom of a mere five months, who is so happy with me and was looking forward to the next thirty years together. But mostly it was the unfinished book that stuck in my craw.

Neighbor Florence interrupted my lugubriousness when she came in with the spare key she uses to feed the animals when we’re away—Bruno, who is with the kids in Bordeaux at the moment, called her when I stopped answering the phone. She found me in the bathroom.

The pompiers came. They were very gruff with me for not calling sooner. I only threw up blood twice, but they explained that all that black diarrhea was blood, too. I felt proud of myself that I can speak French even when drained of blood.

July 21

That endoscopy was a fucking nightmare. I made a spectacle of myself. They couldn’t sedate me for breathing reasons and they don’t carry Valium (I won’t take Xanax because I’m a former addict). They shoved a camera on a tube down my throat into my stomach and probed around in there while I hyperventilated through my nose with tears streaming down my face and everyone ordering me around in gibberish and getting mad that I couldn’t comply. It took five people to hold me down, like I was a dirty feral creature some animal rescue people trapped and were emergency-operating on.

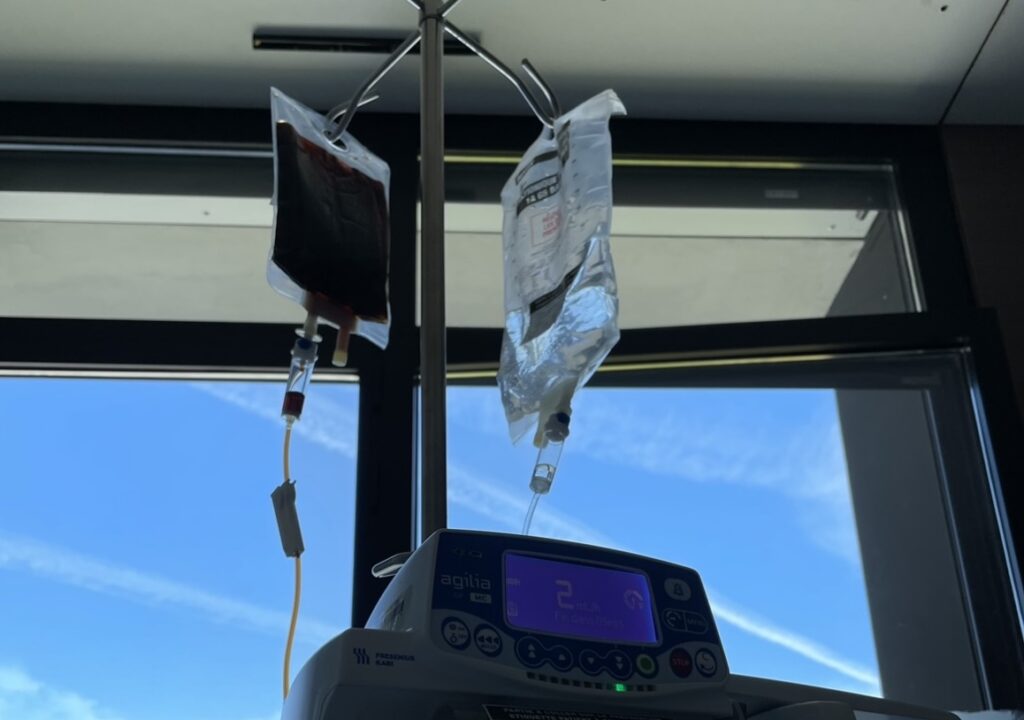

They found a lump in my stomach and will perform a biopsy next week. I’ve lost so much blood they have to keep me here till then. It’s going to be a lonesome week. No vegetarian meals, no Wi-Fi, no translators, and no visitors (COVID outbreak).

Well, it doesn’t matter about how meat-happy the French are: I was just informed that since I am still bleeding internally, they’re cutting off my food and drink and are pumping everything directly into my veins.

July 22

I napped fitfully all afternoon after my endoscopy, and woke to feel a presence. I turned my head and there was Bruno in the chair. He decided to make the six-hour drive to see me for a couple hours before heading back to pick up the kids and drive them to camp. And the hospital changed their COVID policy today.

He pulled his chair closer, saying “You have a nice face.” Now I’m sure he loves me. Only a lover could appreciate a no-makeup, no-blood face. I was so happy to see him I started crying. He said no more stress in our lives; we will build our life around no stress now.

Then it was time for him to leave.

I feel … fading. I’m just a sad baby lying in my bed staring at the wall. But it’s better than dying on the bathroom floor. My dog would have lost his ever-loving mind.

July 23

At 5 A.M. I woke up with a huge swollen upper arm. The nurse missed my vein when he changed my IV, and so the medication to coat my rupture and stop the bleeding flooded my flesh instead. I’m still shitting blood. And I’ve had a really bad headache that had me in tears and I waited seven hours for Advil. I feel terrible complaining because I know it’s no one’s fault. There’s a nurse shortage. But I hate this helpless feeling so much I would rather die a little earlier in my own home than live in assisted living someday.

I had a scan. It revealed another possible cancer on my uterus. And my gallbladder.

The Ouija board said I’d live till eighty-four and I always believed it and I still do. But just in case I die soon, I would like anyone reading this to know it was a very good life, I did every single thing I wanted to and nothing that I didn’t. Wonder is our natural state of being, I believe, and when you don’t feel it, something is wrong, and all you have to do is identify it and then leave it behind. It’s so easy to be happy. You can get there two ways: walking away from something not good for you, or simply walking, in the sun or rain or starlight or snow. I don’t know if that advice applies to everyone. Bruno says I’m always escaping rather than experiencing tough things, and maybe that’s true. I just don’t see any reason to “work through” something. I’m not big on trying. And that includes being okay with dying.

July 25

It feels threatening, being a stranger to yourself. One never knows what a stranger is capable of. I am experiencing weakness for the first time. When I was lying on that bathroom floor, I felt my strength leaving with my blood. Severe anemia completely changes your personality. That’s what a nurse told me. I feel like I lost mine. I lost my limbs—I can’t stand up. I lost my ability to choose what anyone can do to me. “I” flowed out so easily with my blood. How delicate, how ephemeral, identity turns out to be! Who was this person Lisa who my husband and children and friends loved, who I loved? It was a mirage, a long-lasting mirage. So when I go into that hell chamber tomorrow and the snake camera comes at me, there won’t even be the usual “me” to help me through it. I feel a strange loneliness such as I have never known.

July 26

The IV hurts so bad. I asked to have it changed but the nurse said I can’t because I’m running out of veins. I don’t know if this is true, as this same nurse told me my medicine pump wasn’t blocked and refused to look at it (it was). And refused me food, saying I could only have broth because of my ulcer—except I don’t have a regular ulcer, I have lining of a tumor that burst, and I was told I could transition to food yesterday. Bruno knew all about it (after my vast and vibrant expressions of indignation on the subject) and just stood there and let her flirt with him. His buckling to authority is a French quality, I think. Just look at how they behaved in World War II. It’s good in that he can spend countless hours doing all the administration stuff and greasing the bureaucratic ego, which is what it takes for me to live in France. I could never do that. But now I’m seeing the dark side of this quality. I’m seeing the dark side of everything these days. When your definition of happiness is to walk and you’re trapped in a bed with no estimate of when you can leave it, the light goes out.

Messaged with my second husband’s third wife. She asked if I could get up and move around with all the tubes sticking out of my arms. I replied, “Yes, but it’s a lot of rigmarole. Not only that, they keep getting infected. First one arm and then the other shoot up like freak balloons. Now they’re covered in blisters, bruises, and oozing sores. Then they put tape on top of all that. Tape on raw hamburger flesh. Plus I made an enemy out of my nurse. Then she flirted with Bruno and he’s so oblivious he was like, ‘Oh, really?’ ”

My second husband’s third wife quipped, “That’s a really bad Yelp review coming.”

July 27

Had a serious talk with Bruno that if it gets to the point of a choice between quality and quantity of life, I am 100 percent on the quality side.

I was longing to hear the new Joni Mitchell concert my friend told me about, but I can’t play music or movies in the hospital on my American devices, so I asked Bruno to try his phone. He’d never heard Joni Mitchell, so first I had him play one of her songs from fifty years ago. He was only kind of impressed. He said, “She’s very aggressive to her guitar!”

Then the new version. She needed help standing and a backup singer to hit the notes she no longer could, and yet somehow it rang truer and clearer and stronger, like the song had been waiting all these years to be allowed this expression of itself. We were transfixed. I looked over and saw that Bruno was crying and then felt on my cheeks that I was, too. He said, “The body is destroyed but the spirit is intact.”

July 28

The thought of sex with a stranger is pretty horrifying. (Not that anyone’s been asking.) My body is so vulnerable and helpless. Bruno being so attentive to me, like a mother, is attractive in a way I never experienced in my lifelong independence. I sat on a plastic chair with holes in it so he could wash my hair. I got dizzy when I stood up and held on to him until it passed, and his sturdy, bearlike midriff felt good. Solid. I love his body. And mine. These shapes our souls pour into and move around in. It was the first time we’d been naked together without it being sexual. And yet it was. When there is no more question of pleasing and being pleased, turns out there’s a lot more to pleasure than pleasure.

After Bruno went back to Bordeaux, I cried so inconsolably they agreed to take out my IV just long enough for me to put on a dress and sit outside for a few minutes, free of machines, just me and the sun touching my naked arms. I am so weak it took me twenty minutes to get from my hospital room to the bench right outside the exit. I love trees. I love the smell of grass and smoke and just air. I love this world. I love being alive in it.

When they did my daily blood test after, they discovered that water and love and sun had done what bags of ferrous sulfate and medicine and other people’s blood did not: made me a little better.

July 29

Missed my vein with the IV again. Woke at 1 A.M. with familiar swelling and tingling and sense of danger and when the nurse came in and peeled the tape off there were blisters and abrasions. Couldn’t go back to sleep because I had heartburn from having my first whole meal in nine days, and they refused me an antacid, I couldn’t understand why. At 5 A.M. they woke me again to take my blood. Couldn’t go back to sleep because someone sounds like they’re dying down the hall, may God comfort them (as no one else will). The nurses on break below my open window are whooping it up and sucking down cigarettes. I could not conjure a more purely French image than that.

During my sleepless night, I pictured the cancer for the first time. Not with horror like I supposed I would. It didn’t feel it like an invader. I said, “Hello, little buddy.” Actually, big buddy. The doctors all sound strangely impressed with its size. It just wants to live, and we’re all plotting its death by stabbing after a brief nuclear blast of chemo .

Strangely, I’m in a good mood. I’m still working on my book. It’s difficult because I can’t use my left hand, and I’m used to sixty-words-a-minute, both-hands, by-feel-not-sight typing. Now I’m pecking with one pointy finger like a turtle. I forget the end of the sentence by the time my finger gets there. But life always has some level of difficulty. If it’s not something big, we find something little, and if we concentrate, we can make it take up the same amount of space as the big stuff. Difficulty is satisfying. It makes heroines of us. Anyway, I want to finish it in case I die tomorrow.

My prognosis is excellent … I won’t die … I’m just using my cancer like an extra cup of coffee.

August 2

The surgeon said there’s a slight chance he’ll need to remove my entire stomach. I’ve always had a perfect body. Conventionally (I modeled in my youth), but that’s not what I mean. Rather, I’ve had a lucky body. It did its job, never complained, never failed. In risky circumstances, other people would get hurt, not me. I’ve never been in a car accident, never broken a bone, never had mono or Lyme’s or restless legs syndrome. I thought it was just my fate to be unblemished, undented. I haven’t been prepared by life with little problems to build up my immunity to physical insult. I don’t want to lose my stomach! I love my stomach!

The bill so far—two weeks’ stay and all those tests—is fifty thousand euros. Who knows how much the surgery will be. Thankfully, Bruno has the money. He just paid it and said, “That’s life! No need to add problems to problems with regrets.” Hopefully when I finally get my French social security number, it will cover most of it retroactively.

August 3

They’re sending me home for a few weeks to beef up. Literally. I have to eat meat and walk an hour a day and “be in good spirits.” I’m going to be under anesthesia for eight hours and they want to make sure my lungs and overall body can withstand it. I made a face about the eating-meat part and the surgeon said we’re omnivores and I can’t get better fast enough with peanuts and tofu. I said you don’t know how much tofu and peanuts I can eat. That’s when he told me about possibly taking my entire stomach. I said I’d be a cannibal for a month if it helps my chances.

August 4

I’m home! I was so excited to make dinner out of the beautiful tomatoes from my garden, but I’m too weak, so instead I’m lying down in the living room, yelling at Bruno in the kitchen. Things like: “I can hear that flame’s too high!” Maybe it’s the anemia making me nasty. Eh, who am I kidding—I always was the kind to lie on the couch and yell things.

In fact, I’m incredibly sad. I had this magical thinking that if I could just get home, it would be like it was before. It’s not. I realize now I really am really ill. I can’t do my life at this point.

Everyone tells me to fight this thing, be strong. But I can tell it’s right for me to be weak now—because I’m weak. Cancer’s not a foreign body. It’s just a spot of you that forgot to calm down and stop growing. I’m not going to fight myself. And now that I’ve seen how far gone I am, I won’t fight the hospital anymore, either, when I go back. I accept being a patient. I accept letting other people fight my cancer. The staff will be happy to see my change in attitude, I’m sure, and maybe they’ll stop collectively trying to drug me to quiet me down! (One nurse put liquid Xanax in my IV without my permission!)

August 6

Met with a different surgeon. Now they’re thinking to take all three organs riddled with tumors: stomach, ovaries, and gallbladder. I don’t need my ovaries for making babies anymore, but they continue to pump a little estrogen, which keeps me from having a heart attack or stroke or getting just too mean. I don’t want to lose my organs. It’s an ensemble piece!

August 10

I got to thinking about the perfect timing of this cancer. I’m not too old, and newly married to old money. Plus I’m sporty, an optimist, and have faith. (By faith I mean believing everything that happens is right because it did happen, even if it’s a bad thing, in which case it shows you where you don’t want to go, and you go somewhere else instead.) But I’m old enough that I’ve done already the things you really should have a fully organed body for: travel in emerging countries, hikes up tall mountains, and staying up all night doing cocaine and voodoo.

August 15

Bruno’s cousin’s girlfriend does some sort of New Age psychic massage and Bruno wanted her do it to me and I said no thank you, I really don’t want to be touched right now, physically or psychically. He said it’s not a touch massage. I said I don’t want her even thinking about my insides! He said, “I guess I’m more open than you about trying different things.” Which was infuriating, but that’s not the big deal. He infuriates me every day. What was upsetting was it made me realize that I have to protect myself and my path through this, only I can make the choices completely alone, because only I know myself, the core of myself, and what is right for me.

I still believe there is one life and there are no individuals. There are iterations of the one, God separating itself into pieces so it can play, because you can’t play when you’re in complete harmony. But I have to be true to my iteration, my incarnation, my sliver. If Bruno was the one with cancer, he would have to do the same, and I couldn’t go with him. I have reached the place of aloneness.

I wonder how it affects the experience of being ill, to be a ruminator like me. Maybe it’s easier, because over a lifetime of analyzing and articulating, I’ve gathered a group of friends and readers with interest in communicating with precision on esoteric matters. We have the practice of being with each other’s thoughts. So it’s less lonely. Or maybe it’s worse. Because in this dark hour, precision is one of those things showing itself to be nothing more than a lace hankie on a clothesline in a dust storm. For the first time in my life, my intelligence is really beside the point.

August 22

Every day I take tests to give different caregivers information or attend meetings where they give the information to me. All day long the phone rings with people wanting to talk about my tumors. Whenever we take a walk, we run into neighbors and friends who ask about them. The whole family went to a restaurant and Bruno asked to what should we toast and my beau-fils Gaspar said “to when Lisa will come home after her operation,” which is the sweetest thing an eleven-year-old boy has ever come up with. But I’m also tired of everyone’s focus on what’s wrong with me. I do it, too. I can’t think about anything else. I’m obsessed with my malfunctioning. I AM SO SICK OF MYSELF!

I’m up to the last few pages of my book. I’ve been typing like a maniac. Yet I don’t really care about it. I have no idea if it’s good or bad, I only work on it because I remember that there was a time when I, when I was still an “I,” cared about it very much.

August 28

Upon waking up from anesthesia after my surgery, I asked for three things: paper, pen, and more drugs.

They tell me they decided to let a little bit of my stomach remain, so I’m happy. Or I will be happy when I’m not in so much pain. I heard that mobsters shoot for the stomach because that is the most painful way to die.

I’m on so much morphine.

I am so in love with my husband and our six children, and I have a new tenderness in my love for my friends. When I was on the cold operating table under bright lights with a half-dozen people doing things to me, I was scared, and then I felt love coming to me like a wave that I could ride right out of this pain and fear.

I am so in love with life. I am even in love with this surgery! And with every new thing and every old thing. Like the animals’ morning meals. First I let Abe out and cajole him to faire pee pee while Moustique waits patiently in the doorway. He completes his mission and, upon reentering the maison, he and Moustique bump foreheads affectionately five or six times. The cat gets his wet food first, because he’s greedier than the dog. I tear open a pouch and pour it into the bowl while Moustique yells in celebration. Then I give the empty wrapper to Abe, because he likes to share whatever Moustique has and won’t eat his own food until Moustique is finished with his. (He watches him like a perv-friend.) Then I give Moustique dry food and Abe wet food. Abe takes one bite and freezes. He wants to play, watch Moustique some more, go outside, go back to bed with Bruno. He wants to do all of them at once and so does none. I put my coffee on. Every single morning exactly the same.

August 29

I couldn’t sleep for one minute last night. I lay perfectly still so as not to disturb my two IVs, catheter and dangling pee bag, needles in my spine (epidural), breathing cannula up my nose, and EKG buttons and wires. Furthermore, we have one numb leg, strange itchy sensations everywhere, and, of course, pain. My throat is raw from the tube stuck down it during the surgery. Et brûlée d’estomac. Also, compression socks from my toes to my you-know-what. Plus it’s hot, I’m anemic … oh, and I stink. But discomfort is not why I couldn’t sleep. I was too excited. Instead of dreams, I had love-thoughts and -feelings and -images all night long.

I told Bruno of my love-revelations along with my body complaints and his comment was: “Yeah, when I kiss you, I smell surgery.” Ah, classic romantic French.

Iodine and fear sweat. That’s what surgery smells like.

Oh my god, a nurse just helped me get out of my bed to stand and I almost passed out. I can’t believe how in movies they rip their IVs out as soon as they’re stitched up and escape the hospital and run off to murder someone. I just want to turn invisible so they can’t find me when it’s time for me to stand up again and get into a wheelchair to go upstairs.

Tout à l’heure!

August 30

What stale hell is this? My time in the ICU was sweet, but now I’m back in the general gastrological population. In the ICU I was getting 5 to 10 mgs of morphine per hour. Here I receive 5 mgs once every six hours or whenever the nurse gets around to it. Last night I asked the nurse if she could remove my catheter. I can get up now to go to the toilet myself if someone helps me. She said no, there are no doctor’s orders for it. She said it as if it were satisfying to say no to me. I said can you check it then, because it feels like it’s loose. She gave it a tug and said it’s in there. Two minutes later it broke open and spilled a full sack of pee all over the bed, me, my phone. Worst of all, I had to shower off. It was late at night and incredibly difficult; I was not up to it. It could have been avoided if she’d believed me about my own body. I got back in bed and could not sleep. I was in so much pain. And a little scared of the nurse. Finally at 4:30 I fell asleep. At 5:00 she came in and said she was pulling my catheter out. I said no, laissez moi, j’ai besoin de dormir. Plus tard. She said yes we’re going to take it now. I said no, please. She said OUI MADAME. There are certain times when calling someone madame in France means I hate you. She reached between my legs and drew it out of my vagina while I was crying no, stop. I was shaking when she left; there was no way I was going back to sleep, not while she was out there roaming the halls. I was so relieved at 8:00 when there was a change of shift, I was able to sleep for a couple hours until the doctor arrived and opened my curtains and chastised me for sleeping in the day because that makes it hard to sleep at night. But there are monsters in the night, I wanted to say.

I’d heard other people grunting rhythmically and wailing the first time I was in this ward. I never thought I would be one of them. I’d pictured myself as stoic, a hero in a western, Jesus in the desert. But here I was now, wailing away! About two hours before it’s time for my medication, the pain starts getting unbearable. One hour before, moans rise out of me. A half hour before, tears start rolling. Then, if a nurse doesn’t come when it’s time, I lose my last bit of control; I start sobbing, which convulses my stomach, shaking all the stab wounds. I’ve reached a level of pain I didn’t know existed, where there is no such thing as having a thought or being polite or even being alive in the sense that we are used to. There is no love. Not of person, animal, earth, self, or God. There is no connection. There is nothing. I am a howl, a burning sorrowful energy shooting through the night: no skin, no bones, no friends, no wishes.

This evening it was two hours I was left rotting in that final form past the time when I was scheduled to get morphine while Bruno sat beside me, occasionally scurrying out of the room to try in vain to secure relief for me. Sometimes he touched my hand, but it made no difference. If it was awful for him, I didn’t notice or care. There is no embarrassment in Pain Land. At last the nurse came with the absence of pain in a syringe. Within two minutes I was transformed from pain taking the shape of a random human husk back into me. And I could see. There existed a world to see.

August 31

Last night I had a kind nurse. I slept off and on the whole night through. This morning, I wouldn’t say I felt like a million bucks, but I felt worth at least a couple of counterfeit bills after they’ve been through the washing machine with a bucket of rocks to make them look real. I realized how much no sleep and no food had affected my ability to handle the pain yesterday … I didn’t handle it! It handled me. It threw a saddle on me and rode right out of town. I was outcast. Now I’m back. Thank you, angel woman.

There is all this gas from the surgery trapped inside me. Normally people pass gas naturally, but I just don’t. Bruno told the doctor it’s because I’m Anglo-Saxon. We’re a squeamish people. The doctor laughed and said it’s true. So today they gave me a special suppository. A gas one. It was crazy!

September 2

The Bad Nurse was back last night.

I couldn’t feel my legs or my hands. I could move them, but I had no sensation. I didn’t know what it meant. Was I having a stroke? The Bad Nurse stood in the doorway after I rang and listened to my complaint while looking at me with fury. She rushed up to my bed and grabbed my hand in both her hands and crushed it. She said, “Did you feel that?”

Sometimes, very rarely, one of my son Wolf’s caregivers would be like that. Sadistic. I would fire them immediately. I’d be overwhelmed with sympathy and terror for all the helpless people without a hovering mother, trapped in these monsters’ hands. Now I was one of them.

Later I made the terrible decision to ring her again when my level of nausea reached the point I was about to throw up. She said, “You’re not nauseous. You don’t have numb hands. You just have pain. I gave you morphine.”

Nausea is a totally common and treatable response to stomach surgery. Also, she kept repeating my rendition of des crampes as if she had no idea what those words meant, as if my accent is too horrible for a human being to be expected to work with. Imagine being surrounded by people whose language you barely speak, but with whom you need to communicate about things that will make your life much better or much worse. How hard do you think you would try? That’s how hard I was trying. And she ridiculed me.

Finally I fell asleep, only to be immediately awoken by her aide, asking who told me I’m “allowed” to chew gum. It was the doctor who suggested it. I’d been chewing it like an hour earlier, when I told the nurse about my nausea. Why didn’t she ask about it then, if she really felt invested in my health and the possible harm a piece of gum may do me?

Just before dawn I awoke to a familiar sensation: my IV had come out of my vein and was dripping medicine and sugar water into my flesh instead, making it swell. The nurse wouldn’t come; sent the gum-spy to answer my call. I asked her to at least stop the medicine and water if she couldn’t change my IV, like the other aides did, but she said no, only the nurse could touch my IV. And they left me there, pain around the site building more and more intense for three hours until the day crew came on.

If the tone in this entry is a bit cardboardy, it’s because it’s from memory, days later. I was too heartbroken, perhaps for the first time in my life, to write contemporaneously. And writing is the lizard part of my brain, the first thing I got (learned to read and write at two years old), and it will be the last thing to go, like songs often are for people with senile dementia. She broke me.

The day nurse found me in tears—the slow, quiet kind. I asked for morphine even though I hadn’t taken it during the day for two days. The sooner I get off it, the sooner they’ll let me go home. She said let me give you something milder first and in ten minutes I’ll check on you again and if you need the morphine, I’ll give it to you. I burst into full wet-face noisy crying at that.

Then suddenly I stopped reacting, got cold and distant like I did when I was young. I rose above myself, and from that vantage point I examined the situation. Hmm. I didn’t really want morphine. The pain was manageable. What I wanted was for someone to listen to me. So now, even though I was asking for something I actually didn’t want, something bad for me, the nurse telling me no (or “not yet,” really) was confirmation to my bruised mind that my reporting and sensations aren’t real, don’t matter, and no one will do anything about it.

Abused children so often go on to abuse themselves through addiction. What we want is for our mother to stop everything for a second and look at us and see us. She doesn’t have to save us from what happened. Just be with us, just show us we’re real—that’s enough to save us, probably. Sometimes drugs feels like the closest we can get to that.

When the nurse came back ten minutes after the mild pain reliever just like she promised and asked if I still wanted the morphine, I said no. (Postscript: I never took it again.) I smiled and said merci pour le bon conseil. And I asked to speak to my surgeon.

He came in looking like he was heading to a discotheque, in a white silky shirt with crimson-and-purple flower pattern! I was so surprised to see him in this fashion. It seems he comes in even on his days off to check on his patients.

I have a hard time telling on someone. But I told my surgeon about the nurse because I’d trusted him with my body and now someone had come along behind him undoing his good work. So much of recovery is feeling like the captain of your old ship again. For two nights, that woman took the wheel away from me. When I was most vulnerable and takeable. What a terrible thing to do. My surgeon put his hand on my shoulder and said, “Ma pauvre.” He sent in some special woman for reporting. I told her my story and she said, “Completely unacceptable.” It sounded like that nurse will be fired, which will be best for everyone—for the patients she hates, and for her, to go do something in the world that won’t infuriate her.

September 3

The special woman for reporting must have given instructions to the oncoming night nurse to handle me gently. She explained everything she did and just had a balmy energy. I slept.

When Bruno came to visit, I got really irritated when he left my closet door ajar (Why do people do that???) and later for saying “crazy world” one time too many. I said find a word other than crazy sometimes to describe what you mean. He said, “Oh, you’re back! My bossy baby is back!” He said my face looked alive again. My surgeon came for his inspection and apparently saw the same face, and said I could go home that afternoon.

Bruno said that, oddly, his immediate reaction to the news was sadness. The moment the war is declared over, you look around at the familiar desolate landscape and dreary MREs and the boredom and the shattered lives, and you realize you’ve learned so well how to navigate this land, you’ve forgotten about the other. He’d gotten used to waking up alone and having his quiet morning and then driving to see me and parking in “his” parking spot and if there’s already a car there, grumbling.

My first reaction was fear. I’m not the same, so home won’t be the same, either. I will be an intruder in someone else’s house, someone else’s marriage, someone else’s life. In times of chaos or duress, there’s no room for soft emotions like trepidation or the blues. Now there was.

A new guy got wheeled in, and he brought the pain howl with him. Funny how so rapidly it came to sound foreign to me. I’m on the other side of that now, and it’s as if I had never been there, as if I no longer believe it really exists.

Every once in a while during the two months I’d been sick I would get a lustful stirring about Bruno. I certainly didn’t want to act on the impulse, but it was reassuring to know it was still there, waiting. I’d wondered if Bruno had the same about me. Then I saw myself in the full-length elevator mirror. It would be impossible to think about touching me. I looked so injurable. I saw a woman hunched over her wound like an old crone, belly distended (from undischarged surgery gas and from starvation), skinny legs in compression socks, skin white as paper. And the eyes of the woman looking back at me in the elevator were dead.

September 4

A nutritionist and the surgeon explained the complicated endeavor of how one best functions with a 25-percent stomach.

Six or more small meals a day. Seriously small. If I pack my stomach beyond its capacity, or don’t chew for a long, long time, there will form a ball of … “Have you ever seen a video of an owl vomiting up a mouse it had eaten—hair, bones, everything?” asked Dr. Charre helpfully. “That’s sort of the ball you’ll get, and we’ll have to operate to remove it.” So. Soft food only, neither hot nor cold. Start off with only applesauce, yogurt, meat, eggs, pureed veggies (but no cucumber or tomato or anything with long fibers, like asparagus or lettuce), white rice or bread only—nothing complex or multigrain. No water with your meals. No sparkling water ever. When cooking, use at most a tablespoon of oil. After the first month, I can reintroduce food items one at a time and find out if they make me sick or not.

“This is going to completely change our life,” Bruno said.

“No it won’t,” I said. “I’ll just pack snacks.”

The stomach is a storage unit, Dr. Charre explained, and now instead of a Mack truck, you have a closet. For the next year or two until I stretch this thing out, after each of my six to eight daily meals, I’m going to have to run to the bathroom.

Okay. This is going to completely change my life.

Then the surgeon told me that iron is metabolized in the lower stomach only, and mine is completely removed. So, I’m going to have to get blood tests twice a week for maybe the rest of my life, and probably blood treatments. I’m going to be anemic to some degree for the rest of my life, and anemia drains the body and spirit. I’ve always had such a fine body and emotions. Now I don’t. I have to take many pills throughout the day and inject myself with a giant needle in the belly every night.

There’s another way my life has changed: I am going to have medical expenses. I’m going to be financially dependent on Bruno for the rest of my life. I guess that shouldn’t be a big deal—we’re married, he’s generous, I have no problem with redistribution of wealth. Except that it has been a great comfort to me to know I could leave anytime I want. In a French divorce, the wife gets only what she brought into the marriage, and I brought nothing financially. Still, I would have been okay on my own again on my little income, as my needs have always been modest. From now on, they would be immodest. I know everyone else has dealt with health costs and I have nothing to complain about. But this is new for me. And I don’t want it!

That, too, is new: ungratefulness. Whatever bad things have happened to me, or whatever bad things I’ve done, I accepted as interesting experiences, was grateful to them. I never fought with fate. It’s not that I want to fight it now. It’s that I want to go under the covers and hide from it.

September 5

I haven’t felt hunger since my surgery. My stomach is so small, a few bites fill it. But if I get down to 49 kgs (I’m 5’8”, and currently am at 53 kgs), I have to be readmitted to the hospital. I’ll have to stuff myself off and on all day long. I may never be hungry again. You don’t realize what a pleasure it is until it’s gone. The building urge, at first a whisper, slowly growing till it’s the only voice you hear—it’s so sure, so true. And then you satisfy it. You satisfy yourself. Fill your own lack. Over and over. What a magnificent life! We’re hunters. Hunters of pleasure. And we succeed. Every day.

Bruno brought my favorite snack. Hummus and pita bread and stuffed grape leaves. I experience the memory of how nice eating had been, but only the memory. The act of taking bites feels like taking medicine now.

Shortly thereafter I began to vomit. And vomit and vomit.

I felt lyrical when I was touched by death and morphine and a pain beyond the world we know. I felt taut like a bow and arrow about to be flung. Now I’m flat. I don’t want to leave my room, much less zing into the unknown sky. Yet I don’t love my room. I don’t love. I haven’t the energy for it. I don’t even feel like crying. What’s the use?

September 6

Gaspar was teasing the dog, forcing kisses on him. His sister Maelle and I asked him to stop. Finally Abe did something he’s never done before: bit Gaspar really hard, on the chin. Gaspar was screaming, it was awful. Blood. We all yelled for Bruno. When he came, he didn’t get a bandage for Gaspar or even ask if he was okay. He immediately launched an assault on me in English. He said this was my fault for coddling the dog. He said I should marry the dog, I should live in a zoo. He came at Abe and was holding him down and making him squeal. Gaspar was pleading with him to stop, Maelle and I were shocked, frozen.

Then a switch flipped in me and I grabbed Abe and fled upstairs to the bedroom. Bruno followed, mocking me until I screamed “Get out!” One of my stitches had torn open; I was bleeding. Now I was the one following him. I ripped open my shirt and showed him my blood and cursed him in a redout.

I’d moved more in the last ten minutes than in the last ten days. Good exercise for the day. Bad flood of cortisone.

I don’t blame him for aggressing me when I’m sick. Being married, you’re going to be at your worst sometimes with each other. Being a caregiver is very hard. Sometimes I was a monster with my disabled son Wolf. I was so stressed.

I don’t blame him, but I don’t accept it either. Blood came out of my stitch. This is too much. Change is coming. I don’t know what change exactly, nor do I have the strength yet to make a stand, but I will. I told him so later. He said, “Thank you for telling me, and I miss you.”

I miss me too.

September 7

I am in a pit. Bruno brings my meals on a tray, the same few items I know won’t make me vomit: a steak he found online that is the only cruelty-free meat in France, broccoli with mayonnaise, applesauce. I could move more, but I don’t. It’s strange to recognize total depression and it doesn’t change anything. Normally, seeing something instantly transforms it.

I’ve asked Bruno to leave me alone, to sleep in another room, to let me walk Abe alone, to basically not talk to me.

I made an appointment with a therapist. I don’t really feel like getting out of this depression, but I can feel my old self inviting me back to the world and telling me how to get there. She’s so encouraging, so confident. It’s easier to let her have her way than to argue with her.

September 8

Bruno has always seen me as messy and not making myself belong here and afraid of men and seeing disrespect everywhere. He could see me as a dreamer and having a unique way of belonging in the world, and that’s who I would be. Married people create each other. We have to be careful of what we believe about one another—our friends, coworkers, lovers, children, pets, even strangers—because that is the part we make grow. And we have to be careful about who we hang around with—what they believe about us. Right now the only person I’m hanging around with, the one person who dares to enter my dark room with pieces of meat and applesauce and pills, the only mirror I got, is a dismal mirror indeed.

September 9

Bruno said, “You were right. I do make people feel small. I just saw myself doing it to Gaspar. I was helping him with his homework and I started picking on him and tears fell from his eyes. I am going to go to him now and tell him I’m sorry and that I’m going to work on myself with a therapist. Will you take a moment to celebrate with me?”

I said, “I’ll celebrate with you when you actually do it. At this point, hope hurts.”

September 10

My medicine can’t work because I keep vomiting it up.

I don’t know why I’m extra sick today. Could be because I had a few bites of a fajita last night cooked in oil. Could be because I didn’t walk the dog. The surgeon said the more I walk, the better.

It’s 6 P.M. I’ve been trying to psych myself up to walk the dog for ten hours now. I’m afraid of puking in the street. This vomiting is so awful. I’m desperate. I also kind of don’t care. Go ahead, vomit, keep coming. I really do wish I were dead. So many people deal with chronic health problems … how do they do it? I’ve only been ill a couple of months and I’m destroyed. So many uncomfortable sensations, which I could accept singly, but en masse, they sink me. Like that I have a too-tight belt on, it’s biting into me. If I could just loosen it, I’d be okay. Several times a day, for a split second, I actually go to loosen a belt that doesn’t exist.

Oh well. I’m off to embark on my stupid constitutional now.

September 11

I’ve been lying here marinating in hate. Mostly at Bruno and how I would love to leave him, but also a vague hatred for all things. He just came in and asked how I was. I said nauseous. He said and mentally? Is there something against me I can work on? I said we should talk when I have a clear head. He said you’re beautiful. I said no I’m not. He said, “I don’t lie. There’s something touching in your face now. Like you’ve let go of so many things and only the core of you remains.”

September 12

Bruno came in to kiss me good morning and I grimaced. He said you don’t really like me to be here, do you? I said I’m like an animal; I want to be sick alone. He said I miss talking to you. I said you can write me a letter.

Later he entered my bedroom nervously with his afternoon coffee, which I have taken one sip of every single day we’ve been together, like his grandmother did with his grandfather’s coffee. “Will you take it?” he said hesitantly. “Is it too late?” I took a sip. “There is hope!” he cried. “The day you won’t take a sip is the day I will know there is no more hope for me.”

It was pathetic in the sweet sense of the word. Bruno’s whole life right now is devoted to helping me get better, and it’s not working. He just keeps doing my errands, waiting on me, and I only get sicker, and it’s so obvious that this person he’s waiting on doesn’t even like him.

September 13

I’m supposed to eat six meals a day. I manage maybe one and a half. Any more makes me nauseous. I cut the meat into small bites and chew for a long time like the doctor told me to—longer than the flavor lasts. I give a tiny piece to the dog and one to the cat for every bite I take. They are patient sentinels, one at either side of my bed. I hate eating meat. It makes me feel sick. It makes me feel sick to inject myself in the stomach with a giant needle every day. It doesn’t hurt that bad—what’s upsetting is that everything I do is what I don’t want to do.

September 14

Hearing Bruno’s ex-wife Emilie laughing vibrantly downstairs while dropping off the kids, I’m struck by the contrast. I have no laughter. I have nothing to offer. In my previous life, I was almost never jealous or insecure or comparing or complaining or petty. In my illness, I am nothing but. It’s not like I became something. It’s like I unbecame everything that made me me.

Twenty minutes later and the four of them are still down there talking animatedly. I seethe in my bed like a poor relation stuffed in the attic, even though it’s me who put me here. I could go downstairs and say hi. But I don’t want her to see me. She is fit and young, and I am a disgusting ghost.

September 15

In my sickbed, huddled around my shredded bit of stomach that remains, I have become enormous. I am all of discomfort. I am all of apathy. I am a sea. I am the space created when you declutter a hoard, and all knickknacks not cherished, all puzzles never done, uncomfortable chairs never sat in, have all been carted away. I am space, and space is cold.

Bruno says when he tries to hug me, I’m not there. He wonders when and in what altered form I will come back to him. I almost remembered the world, listening to Pavarotti this morning. The day was still bathed in gray, but I could see it in the distance: beauty. That’s what being alive is, I think. Awareness of beauty. I wouldn’t go so far as to say I felt alive again listening to Pavarotti, but for just a moment, I could see how it could be possible again for me someday. Then I had to run for the toilet.

Bruno has to hear me vomiting and moaning night and day and he isn’t even allowed in the bathroom to bring me a glass of water. He must be lonely out there in the rest of the house, in the world. But there’s nothing I can do for him.

September 16

After throwing up this morning, I decided to telephone Bruno to come help me walk back to bed. I could have waited a few minutes till I was strong enough. But I asked him to help me because I knew it would help him. A few days ago I thought: You want him to be a better husband, but what do you do for him, really, as his wife? I couldn’t think of anything. This is love—making his experience of my illness less awful, despite it making things a little more awful for me. I can’t feel myself loving him, but I know now it’s there.

September 17

After my fourth time vomiting today, I staggered out of the bathroom and said to Bruno, “Call my doctor.” He said it’s Sunday, he won’t be in. I said call somebody, or take me to the emergency room. He called the gastroenterology ward and they said if I throw up again today, take me to the ER, otherwise my doctor will call in the morning.

September 18

When Dr. Charre called, he was so kind. The first thing he said was: “What do you need?” What a marvelous question. Yes you’ve had years and years of schooling, but I’ve had even more years inside this one particular body and spirit. I told him I was nervous because I started getting better and then I got a lot worse. It made me think something had gone wrong. I was scared. He said this happens a lot after stomach surgery—the gut is nicknamed the second brain. You get depressed and anxious, and that can start you vomiting … something about worry contracting your muscles. And the more you vomit the more depressed you get. He recommended going out in the sun every day—sitting if I can’t walk. And connecting with people. I haven’t talked to anyone for a week … really not even Bruno and the kids. He said in English, “Hang on, kid.”

So I called my best friend, Rachel. She cried. I didn’t, because I never cry anymore. I did laugh once, which I also never do anymore. So now I can’t say I never laugh. I went and sat in the sun. I walked Abe. I finally texted back my friend here, Valerie, who had been sending me pics and news and worry. I texted Sadie that I’m ready now for a phone call whenever she gets the time. I texted Roudey (Wolf’s caregiver) that I’m slowly getting better and hope to come visit in October. I texted back Emilie about how I was doing (the children are with her this week, and they’d told her they were concerned about me).

And I didn’t vomit. God bless Dr. Charre.

September 19

Woke up, felt good, planned three activities.

1. Do my hair and makeup.

2. Connect my friend/publisher Jeff with the comics community.

3. Have lunch with Gaspar and Maelle when they’re home from school.

Well, it’s four o’clock and I haven’t done any of them. It seems I exhausted myself just thinking about reentering the world. Still, that I wanted to do anything is entirely new.

September 20

This morning I was all revved up to actually do at least one item on my list … and then Bruno came downstairs and I saw the Face. He looked over my shoulder at the article I was reading. Then he exploded into a twenty-minute rant on 9/11, George W. Bush’s war crimes, America supplying Ukraine with weapons and now French people are being asked to pay more for fuel, me not knowing what I’m talking about, and how hypocritical is “my side” (the left). He put all this shit into me because he needed to put it somewhere and I was there.

It was the first time in days I felt well enough to hang out in the living room. I no longer felt well. I went back to my room.

September 21

Today, I walked to the phlebotomist’s on my own. I worked out my new insurance problems with the receptionist. I walked home without stopping to rest once. I told Bruno how proud I was of myself. He said congratulations, but I could tell he was a little glum about it. I said, “Are you sad to be losing total control over me?” He looked surprised and then he smiled. “It’s scary to be with you,” he said. “You see everything.”

I am so tremulous and diffident that if my number-one connection to the world is puppeteering me to make sure I stay helpless, perhaps I will just go down and not come up again. I can’t fight gravity and my husband.

September 25

Cognitive behavioral therapy is a miracle! It only took four days of homework before I saw what was wrong. Each event precipitating a negative thought was Bruno treating me like a child. When we saw our friend in the street and she asked how I was and I started telling her in halting French, Bruno interrupted and answered for me, like he always does, despite my repeated requests to let me speak. Each reactive physical sensation was the same: getting smaller and tighter until I’m a speck of dust and I’m sailing away. And then for the “What Did You Do?” box, my answer was always: “Nothing.”

You know what? I am not a child. I am not a speck of dust. It’s not me to do nothing!

I felt life rushing in. I felt joy. I felt self. After picking up pills at the pharmacy, I made an appointment at the hair salon and then went to the market and bought soy dogs and baked beans. Yeah, everyone told me to eat meat. But if it makes me want to cry every time, how healing can the proteins be when I’m simultaneously being flooded with sorrow hormones? I bless my surgeon for knowing his business and taking such good care of me, but now it’s time for me to take care of me.

September 27

I’ve been seeing all that I lost: my sex drive, my naivete, and twenty-five pounds. I decided to see what I gained.

I took off my clothes and stood shivering before the full-length mirror. It was like a photo of someone rescued from a concentration camp. Even my bum got a flat tire.

I saw that I’m still standing, jagged bones and not much else. I saw softness on my skin, a kind of peace. I saw pity and forgiveness in my eyes instead of the twin lightning bolts that used to shoot out of my brain through the sockets. My lips and jawline are at rest instead of pressing into lines of eager tenseness. And my scar is beautiful. It just fits perfectly, geometrically, with all the lines of my body. Everything else of my body is just there, is how I was born. My scar tells what happened, what I passed through. I love it.

And my new personality? I’m still protecting myself from the world. I am an open wound. I’m soft.

September 28

I decided to stop hiding myself. I said to Bruno while we walked the dog, “Okay, it’s time for you to see my scar.” I lifted up my hoodie right there in the street and he was shocked. “It’s so big!”

He then “joked” that everyone would stare at us when we went swimming, and that we would make so much money putting me as an attraction at the freak show in the circus. Why on earth would anyone say that? He just kept being an idiot and I just kept walking until finally I started crying, at which point he said I was too sensitive and you have to be able to laugh at anything. He said, “If you think I don’t find you beautiful and desirable, you’re crazy, and I can’t do anything with that.” I said okay, I’m crazy, I really don’t care.

As soon as we got home, I looked at airplane tickets and they were $2,500?!

Bruno said, “I shouldn’t have been that hard. I didn’t know you were fragile about how you look. When the surgeon told us he would cut you open and started to reassure you about the scar, you said, ‘Oh, I don’t care about that—I like to have a picture of what happened in my body on my body.’ I thought that was so unique, so you. I was really charmed. In that moment, I fell in love with you all over again. So I thought it was okay to say my stupid jokes. You are always going to be desirable to me. It’s not about age or your figure or a haircut—it’s something shining in you, coming out of you, and I want to be near it. It’s warm, you’re glowing: you’re very alive. It’s different now. You’re quieter, softer—so it’s a quieter, softer shine. We will have different experiences now. I don’t even know what it will be like. We will discover.”

September 29

Sadie called. We hadn’t talked in months! At the end, she asked if I would like her to call again tomorrow. I said I would love that. She asked if I really would. I said I really, really would. She said, “I’ll call you every day on my lunch break then.”

I felt lucky. My previous high-energy self was too much for her as an everyday thing. We talked or texted only once or twice a week. If my new self is more reachable to my daughter, if that’s the only good to come out of it, then everything I went through is totally worth it.

September 30

My mother would call me an alien or monster or robot or just like my father. My father implied he and I were gods together, unreachable to my mother and the other plebs. I did not feel superior, but I did feel always different. I felt like an emissary from another kind of being, not human. A spy. I felt eternal.

Now, I feel human. I feel destructible. I can’t say a new awareness of mortality makes life more precious to me, as life has always felt precious and miraculous. But it has made me feel like I belong here on earth with people, rather than that I’m studying them. They’re not a them anymore. We’re us.

October 12

I decided to leave Bruno.

When the trainer arrived to take Abe to the park, Gaspar was doing his Gasparly procrastinations, and Bruno was so angry! He started picking on me. I said handle your frustration, don’t take it out on me. He continued to criticize and belittle. I said stop it! He stomped off without a word. The trainer, Maelle, and I did the lesson, and when we went back inside, Bruno was in his chair sulking. When the trainer asked shall I come back next week, Bruno, having put me in silent treatment, said to Maelle, “Tell Madame to schedule whatever she wants. She does everything perfectly, let her run the calendar as well.” The trainer looked shocked. Maelle and I assured her don’t worry, it’s not you, Papa is just a moody man, it will pass. She was not reassured. It hit me that I probably feel inside how she looks, but I’ve numbed myself in order to get through it.

Life is not to be “got through”! I booked a flight to America, and then to Belize. Let me become my new self in the sun and without him.

October 15

It’s been impossible to think of engaging in “the act” without fearing I’ll get broken. But knowing I’m leaving soon, we started kissing and then it happened. I didn’t feel the usual physical stuff; I was numb. So many muscles and nerves destroyed. But I could feel him loving me. Love as an actual thing, like a … like a shovel …in action. It felt good, not at all like before, but … delicate. Oh, it was marvelous to feel something other than sick and weak. I enjoyed his healthy, kind of fat, kind of brutish body. I felt wonderful and surprised being able to handle him on top of and inside of my wraithness. It was so nice. I said, “If I wasn’t already married to you, I would marry you right this minute.” I couldn’t believe I felt that way when days earlier I was wishing I’d never married him at all. Sex is so powerful. So strange that I used to be so promiscuous. No wonder I had so much trouble and chaos! Sex with strangers is like driving drunk.

I decided to buy a return ticket to France after all.

October 22

It is so relaxing to be in my own country again with my own language and familiar pace and knowing what things mean and my own food. French food is superior, but when you’re ill all you want is what you’re used to.

I haven’t done anything since I arrived, not even seen my kids. I didn’t respond to the IRS, who rejected my quarterly tax statement and want me to give them something, I’m not sure what, but I’m pretty sure I don’t have it. I don’t want to give anything to anyone. I just want to be with the person (Rachel) who has known me since I was a kid and wear pajamas all day and deal with the cats who are sixteen, sixteen, and eighteen. Dodds is blind and deaf and tiny but really bossy. He requires ice cubes in his water dish at all times. He insists on going out in the woods, ready to fight bears and foxes he wouldn’t even know were there until they breathed directly into his nostril (he’s losing his sense of smell, too). He expresses himself by bellowing into the void. The second one I call Skinny or Hundred-Year-Old Cowboy because she walks as if she just dismounted a horse she’d been on for sixty days straight. She seems to be dying of kidney failure. The people Rachel adopted her from told her don’t let her have too much food or water, but we let her do what she wants. She’s on her way out—let her exit by the door she finds sweetest. The third I call Biggie. She seems haunted.

My first day here I weighed 114 pounds. (I’m supposed to weigh 135 at my height and age.) Already I’m at 116.5!

October 25

Hung out with Wolf. He said, “Climate change is out of control. If man can create weapons of mass destruction, man can create methods of mass healing. But it better be soon, because in a disaster, the weak are the first to go, and that’s me.”

I said, “I don’t think you’re weak, Wolf. Look at all you’ve survived, and you’re still here, you’re still optimistic and kind. I think that makes you very strong.”

He said, “Well, I’m not strong, but maybe I’m holy. Because God breathed into me. Only a little holy … I don’t want to get too big for my britches! Holiness is a gift we borrow, never possess.”

I sent Bruno photos and he said he’d never seen me before like I am with my children: upright posture, centered, calm, available, and you can tell, he said, this way of being is eternal. He said maybe that’s how I’m recovering—when you’re sick you want your mother, and since my mother is dead, I found her in my motherland and in myself as a mother.

October 29

In France, I was surrounded by the fashionable and felt—at least after having three organs and my confidence removed—like I had to do something to look nice for the world, and for my husband who was used to elegant wives. I bought hair products, Dior makeup. My hotel in Belize doesn’t have a hairdryer. And anyway, the humidity would undo any configuration I twisted my hair and face into. So I don’t.

I bought a bag of unshelled peanuts from a guy’s backyard and two bananas, all for fifty cents, and that was my breakfast the first couple of mornings. I got a bit of the French time zone in me still, so I’m up at 3 or 4 A.M. I make my little breakfast and eat it on the patio by the fist-size light of my phone and listen to the sounds of the darkness all around. In France the food was wonderful, and Bruno was wonderful taking care of me, but I could see how I was exhausting him, and I turned away from him and into my own painful sorrow. I’d chew staring at a wall and I felt no connection to the life of this food before it came into my mouth. I felt no connection to life. Here the food is not, hmm, choreographed like in a French restaurant, but it’s honest. I eat and eat, the fish on my plate having sprung from the blue-green sea just at my feet, not by trawling—they’re careful to not indiscriminately overfish … there’s plenty for everybody, no need to abuse. It’s an outdoor life. Some restaurants have picnic benches or hammocks in the sea. You feel like a mermaid, eating and drinking with the lower half of your body underwater, warm. To eat under the stars, in moving air, under palm trees and banana trees, with dogs or horses loping about, you just feel part of the world. You feel hungry.

October 30

I snorkeled and did not pop my head up as instructed to listen to the name and characteristics of whatever creature passed our way. I kept my ears underwater and listened only to the sounds of my own breathing. My body swayed with the grasses. I’d seen grander reefs on TV, but seeing something is so different from being with it. Resplendent. Because I don’t have a GoPro, I couldn’t take pictures of it. Knowing I could not show this to anyone else in the world, that it was just me and the creatures, gave me such a feeling of privacy, of … being a little kid getting away with something. After three hours of snorkeling, on the boat ride back to shore, everyone took out their lunch, but I’d forgotten mine. A fellow American offered me a single Pringle from his tiny stack. I don’t know if anything ever tasted so good.

November 3

I climbed and swam in a cave in darkness, bats hanging above, fish nibbling at my limbs. Water up to your waist, water and air the same temperature as your body so that you almost can’t tell the difference—what’s wet and what’s dry, where does my body end and the water/air begin? We’d switch our headlamps on for the tricky spots, then the guide would instruct us to shut them off again and be still. There was no light at all, and no sound.

My first husband, Jean-Louis, recently converted. He said he’d discovered that God was the absence of God. Was simply absence. He had this revelation after he fell off a ladder and refused to see a doctor and could not move out of a sitting position even to sleep for a week.

In my illness, I felt myself as nothing rather than something, anything. The nothing I experienced in the cave was different. I experienced it. I was not it. I was in it, not the whole nothing. Pain can feel eternal, can eat everything, be everywhere.

I’m glad to be here, and not everywhere anymore.

Lisa Carver published the nineties zine Rollerderby and has written twenty-four books, including, most recently, No Land’s Man. She lives in Montmorency, France, with a bunch of stepchildren and animals.

Copyright

© The Paris Review