Abortion Is Galvanizing Voters. Michigan’s Ballot Measure Will Show Us How Much.

“I just need some space” is a disingenuous way to tell a romantic partner you’re Just Not That Into Them. As the top Michigan court ruled last week, it’s also a disingenuous way to attempt to remove from the Michigan midterm ballot an abortion-rights referendum that received 325,000 more voter signatures than the required 425,000.

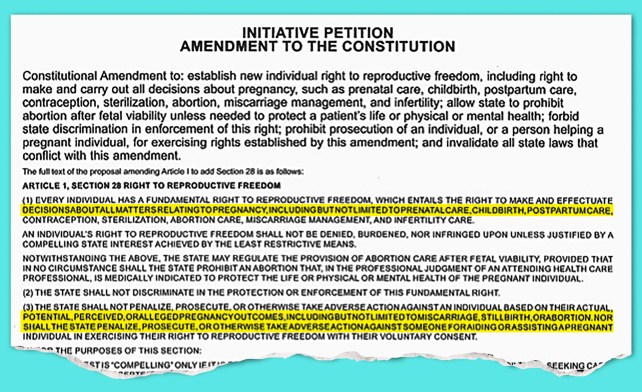

But that’s what Citizens to Support Michigan Women and Children argued last month in a complaint to Michigan’s Board of State Canvassers. The anti-abortion group alleged the proposed ballot measure text, which sought to explicitly insert into Michigan’s constitution reproductive rights up until fetal viability, lacked enough spacing between words, rendering the verbiage into “groupings of letters that are found in no dictionary and are incapable of having any meaning.”

To be clear, the amendment is at the very least legible. Restaurants and magazines probably shouldn’t employ the ballot measure’s maker to design their menus or page layouts, but it’s not the “hodgepodge of nonsensical gibberish” that Citizens to Support Michigan Women and Children made it out to be.

Part of the proposed amendment to the Michigan constitution.

AP

Nonetheless, the spacing complaint culminated in the amendment being blocked from the ballot because it needed the sign-off of three Board of State Canvassers members, and the group was split 2-2 on their decision along party lines. In a last-ditch effort, the abortion-rights group Reproductive Freedom for All, which spearheaded the ballot initiative, requested the state’s highest court weigh in on the issue.

In a 5-2 decision on Thursday night, the state Supreme Court ordered the ballot referendum to be reinstated in the upcoming election. The Michigan Board of Canvassers then voted unanimously to follow the court’s order on Friday, which was the state’s deadline to certify ballots before clerks can begin sending them to voters ahead of the November 8 election.

But if the back and forth over typography seems trivial, it’s because the stakes resulting from the decision to place the referendum on the ballot are anything but—and not just for Michigan.

More so than any other individual race or ballot referendum, the results of this measure in this particularly purple state will reveal the degree to which middle-America voters support strong abortion protections in practice rather than in the abstract. This November, Michiganders aren’t merely voting for a US House candidate who promises to advocate for abortion rights in a Congress that has thus far failed to move the needle on the issue, nor are they voting to secure abortion in cases of rape or incest, in the first trimester, or in the first 16 weeks of pregnancy. Instead, for the first time since Roe fell, a swing state comprising many Americans in the center of the I-support-abortion-rights bell curve will have to decide whether to enshrine in their state constitution full abortion rights for all through roughly 23-24 weeks of pregnancy, or leave it up to the whims of future state lawmakers to legislate abortion access.

In a political moment defined by the aphorism, “Roe is on the ballot,” what happens in this race will signal to both national political parties exactly how motivating that sentiment is. “The unknown going into the 2022 national elections and statewide elections is whether this will be a mobilizing issue on the pro-abortion-rights side of things,” says Ken Kollman, a political science professor at the University of Michigan. “That’s the million dollar question.”

The results of the Michigan referendum will stand apart in its ability to answer that question because of how representative the state is of the broader country. Michigan voted for Barack Obama twice, then narrowly for Donald Trump in 2016. In 2020, Michigan electors selected Joe Biden for president. Michigan has a Democratic Governor but a Republican legislature. Its US congressional delegation is made up of 9 Democrats and 7 Republicans.

In other words, Michigan’s politics are often a toss-up. And so is the outcome of this upcoming abortion referendum. Michigan is “a state where the the full gamut of preferences over abortion are very well represented,” says Kollman. “I’d be surprised if it’s a landslide.”

But other races provide some positive indicators for the left.

One example is the anti-abortion Kansas ballot initiative that state Republican lawmakers attempted to pass in August. The initiative would have made it easier for the GOP to enact stricter abortion laws, but it failed in August by a nearly 20-point margin in a primary election in which Republicans were anticipated to have a voter-turnout advantage.

Democrats have also made gains in competitive US Senate races in the weeks since the US Supreme Court reversed Roe. According to polling averages tracked by FiveThirtyEight, Ohio Democratic Senate Candidate Tim Ryan went from being behind Trump-endorsed J.D. Vance by three points in early June to leading the Republican by two points a month later. In Pennsylvania, Democrat John Fetterman has doubled his lead over Dr. Mehmet Oz since the Dobbs decision was released.

None of those data points are perfect indicators of how Michigan’s referendum will fare, though. Nor are the upcoming abortion-rights referendums slated to appear on the ballots of liberal California and Vermont, where support for abortion rights ranks among the highest in the country, a fair comparison.

Generally, support for abortion tapers as gestational age increases. While 51 percent of Americans believe abortion should be legal in all or most circumstances through six weeks gestation, support falls to 41 percent at 14 weeks and 29 percent at 24 weeks, according to Pew Research Center. That negative correlation makes Michigan’s bet on protecting abortion rights through viability a real gamble.

In other words, spacing—from conception to abortion, not between words—does matter to voters. By trying to codify abortion rights through 23-24 weeks, Michigan will find out just how much.

Copyright

© Mother Jones