A Certain Kind of Romantic

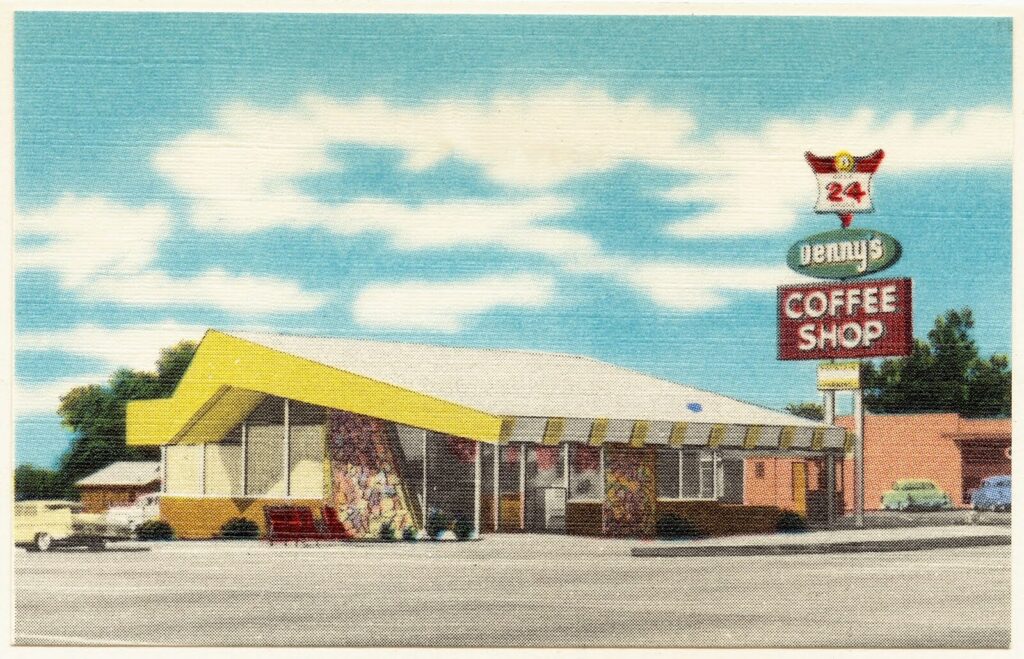

Postcard from the Boston Public Library Tichnor Brothers Collection. Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons.

PARALLEL PARKING

The guidance counselor was my driver’s ed teacher. He liked to talk about football. He didn’t guide me much on driving.

I angled the car into the school lot. We never practiced parallel parking. Therefore, I failed the test for my driver’s license twice.

I had one more try. I diligently practiced between garbage cans in front of the house. It was like playing bumper tag. I didn’t know who got it worse—the fender or the cans.

My dad and I drove to Des Plaines for my last try. I pulled into the street. The instructor had a headache and blew off the part about parking.

I drove to the first McDonald’s on River Road to celebrate my special day. It was as spotless as all the others. But there were hundreds of green pickles dotting the lot.

“I guess they don’t want you to park here,” my dad said.

CAUTION

Whenever I drove, my mother sat in the passenger seat and slammed on imaginary brakes at yellow traffic lights. This was cautionary. When I was on my own, I stopped. When I was with her, I gunned it.

AFTER I GOT MY DRIVER’S LICENSE

I picked up my grandmother at her poker game on Saturday night. She wanted to show me off to her friends. She was in high spirits after the win. When we got back to her place, she drank half a beer to mark the occasion.

My grandmother didn’t want me to drink and drive. That was a laugh. I had never even had a full beer. I ate a pastry in celebration.

Whenever I had a date, I dropped off my grandmother in front of her apartment on Lawrence Avenue. She said, “Good luck in all your future endeavors.”

“Okay, Gram, but I’ll pick you up for breakfast in the morning.”

COFFEE-AND

My grandmother took me to Denny’s for coffee-and. “You’re going to like this,” she said. She ordered me a slice of apple pie with a piece of American cheese on top. I pretended to love it. After that, she ordered it for me every time we went out. I pretended to love it for the next twenty-five years.

DATE WITH DAWN

Dawn’s parents, the Lyons, wanted to know where I was taking their tiny Lyonesse. I explained. They frowned. When would I bring her home? I estimated. They disapproved.

I opened the front door to leave. Dawn was still holding her coat, like a lady. I helped her slip it on. We walked to the car. I sat down in the driver’s seat. The lady was still standing outside. The gentleman hurried around to open her door.

Dawn told me to choose a movie. She didn’t like the movie I chose. She wanted popcorn. I popped out to get it. She wanted butter on the popcorn. I popped back.

Dawn wanted Milk Duds. I didn’t say a word about duds. I had already had Good & Plenty.

I took Dawn to Lockwood Castle on Devon. We sat in a booth by the window. Dawn ordered a large hot fudge sundae. She took two bites and put down her spoon. She was finished.

I had had enough. I told her to eat the whole thing. You’d think she was plowing through the Giant Killer—that had twenty-four scoops with a sparkler and an American flag. Dawn ate one small scoop. This took longer than the movie.

I drove Dawn home. The trip lasted several hours. I walked her to the front door. That was fast.

A FEW DATES

I went on a few dates with Bettyanne. We had bashful back-seat experiences. But I had to give myself a B- because Bettyanne didn’t like me as much as Brett Balmer. He was blonder and balmier than me.

I crushed on Karen because she was cute in green culottes.

Hamlet at the movies: To put your arm around her or not? That is the question.

I went to a drive-in movie with Rochelle and her mother. Not every date likes to go to the batting cages.

Miniature golf is a novelty, not a sport. But Sheryl and I played it like the Masters. She shouldn’t have gloated when she beat me with a lucky shot on the eighteenth. I shouldn’t have pounded my putter up and down on the green.

We went to Riverview amusement park. I was wobbly on the wooden roller coaster. It wascalled the Bobs. I turned yellow and bobbed to the bathroom.

It was hellishly hot. The funhouse was called Hades.

A FEW DATES, SISTER VERSION

My mom wanted Lenie to wear more makeup, to put on false eyelashes and fake fingernails, and to bleach her hair blond. Lenie looked at herself in the mirror and said, “Who’s that vixen?”

Mom made sure that Lenie had a dime for her dates so she could call home if she got in trouble.

When Lenie’s date got too frisky at the drive-in, she climbed out the window. Later, she realized she could have just opened the door.

Lenie had one regret. She was sorry she left her popcorn in the front seat.

Lenie was mad at Phil. She told him to “get lost.” He took her literally and couldn’t find his way home.

Our front door had a little window. When Lenie stood on the front stoop saying good night to Ron, my mom’s face magically appeared. When his friends saw her, they drove away. Ron freaked and fell face down on the sidewalk chasing after them.

Everyone called Randy “the Lamb” because he had curly blond hair. The Lamb told Lenie to stop wearing a short skirt and shiny thigh-high black patent-leather boots. Why? He was upset because he saw her underwear.

Making Fred a flank steak was fine. Cooking it with plastic toothpicks was not.

Neil took Lenie to Lockwood Castle. He ordered tea and toast. He said he had stomach problems. He came back from the bathroom with a wet shirt. He said, “I got whomped by a chocolate soda.”

HAIR OF MANY COLORS

My mom was always dyeing Lenie’s hair. It looked like Joseph’s coat of many colors. In three years, it went from platinum blond to brunette to zebra stripes. Finally, they stripped all the color. It was white, but looked green because she was wearing a green dress. No one noticed. The next day she dyed it red.

TRACK AND FIELD DAY

Lenie’s reputation was shot after she won first place in the shot put. They publicized it in the school paper. Layf kept calling her Moose and so Lenie put down the heavy metal ball. An Olympian was lost.

HURRAH!

Horace Traubel called baseball “the hurrah game of the republic!” Whitman thought this was hilarious. From then on, he called it “the hurrah game!” He said that baseball “has the snap, go, fling, of the American atmosphere.” Whitman had pep. So did Coach Coyer.

SOPHOMORE BASEBALL

Coach also had a bit of Zen in him. Every afternoon he repeated his favorite koan when we were warming up by throwing the ball back and forth: “Quick but not hard, boys, quick but not hard.”

Michael Grejbowski could throw. He was a quarterback who turned me into an end. He was a pitcher who made me regret being a catcher. Grabbo was so fast that I had trouble handling him. I dropped the ball and fired back remarks. He thought they were quick but not hard. We became best friends.

Coyer coached from third base. That left Michael and me on the bench. It was comedy school for high school baseball players. Uncle Mel made a mistake. I didn’t have the stuff to be a good catcher. I had the wrong physique. I lacked the arm. Runners stole on me. Balls got tothe backstop. Coach was on my case. I was getting tired of strapping on the tools of ignorance. It was dumb.

My mother watched me from the fence. “Don’t touch your crotch when you crouch.”

You weren’t superstitious when you got in the batter’s box. You just needed to pick up three pebbles and toss them between your legs before you settled down to hit.

MICHAEL AND I

Mine was a two-car family. Michael came from a one-car family. I could get my mother’s car on weekend nights. Michael couldn’t get his dad’s. Michael and I were inseparable. We had a one-car friendship.

Michael was an only child. He lived down the street from the high school in Morton Grove. Everything in his house was perfectly neat. It wasn’t chaotic like my house. I was afraid to touch anything. But it was good to stop there on our way to a double-cheese Whopper at Burger King.

After we dropped off our dates, Michael and I hung out at Booby’s on Milwaukee Avenue. We never ordered the Big Boob, but we met Ron, the original Booby.

Michael and I talked about sports and girls. We tried to figure out the score.

We traveled back and forth to Gullivers on Howard Street. The owner, Burt, named it after Gulliver’s Travels. That’s how I learned about Jonathan Swift, “who wanted to vex the world rather than divert it.”

The two of us brought our dates for caramelized pan pizza. The four of us talked about sports and books. The two of them told the two of us the score.

Michael and I worked Christmas vacation at Wertheimer. I couldn’t read on break. Maria was gone. We played odds and evens on the job: “One, two, three, shoot!” Loser stacks boxes. Loser sweats. Winner watches. Winner gloats.

Michael and I worked during spring break. This time we played rock paper scissors.

My dad got Michael and me a summer job at the Welch Company, which made scientific instruments and apparatus. We couldn’t play games. We were supervised.

The bald supervisor told us not to call him Moonhead. He told us not to break any glass instruments. He told us not to screw any of the girls on the floor.

“It’s a chemical supply company,” he said, “we don’t expect you to supply the chemicals.”

CHIVALRY AT THE MORRIS AVENUE BEACH

Some burly guy was trying to throw her into the lake. She did not want to go. I didn’t know the girl, but I intervened. Michael stood on the side. He didn’t budge.

The guy was too big. He spit and hit me in the chest. I spit but missed. He said, “Really?” Then he spit again. I missed him again. I couldn’t bring myself to spit on anyone.

It wasn’t a genuine fight. We just shoved each other around for a while. The girl went for a swim.

A CERTAIN KIND OF ROMANTIC

Mom said she was a romantic. I gave her flowers for her birthday. “Flowers are a waste of money,” she said. “They don’t last.”

We took her to a Chinese restaurant to celebrate Mother’s Day.

Mom cried because the food was bad.

This essay is adapted from My Childhood in Pieces: A Stand-Up Comedy, A Skokie Elegy, which will be published by Knopf in June.

Edward Hirsch, a MacArthur Fellow, has published nine books of poetry, including The Living Fire: New and Selected Poems and Gabriel: A Poem. He has also published seven books of prose, among them How to Read a Poem and Fall in Love with Poetry, and 100 Poems to Break Your Heart. He has received numerous prizes, including the National Book Critics Circle Award, and is currently president of the John Simon Guggenheim Memorial Foundation. He lives in Brooklyn.

Copyright

© The Paris Review