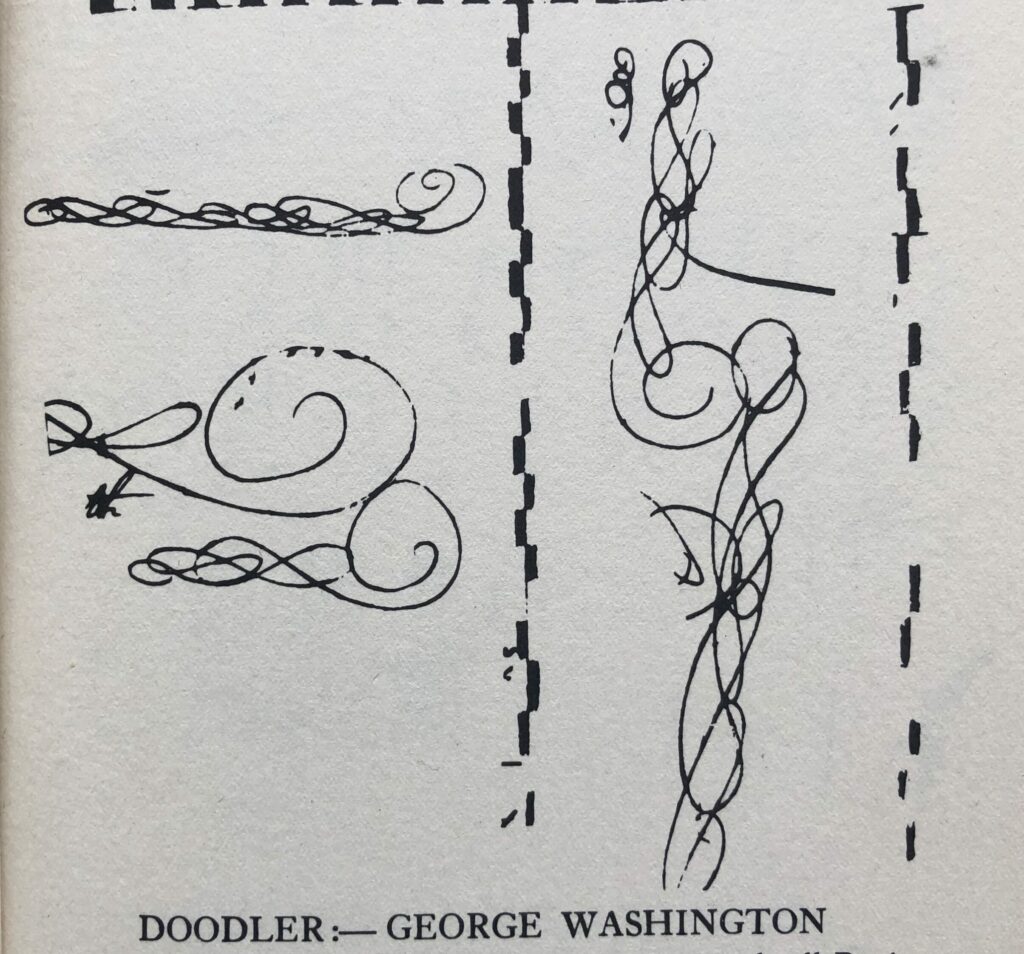

Some doodles by George Washington. Page from Everybody’s Pixillated: A Book of Doodles by Russell M. Arundel, 1937. Photograph by Polly Dickson.

Doodling today is not what it was. Or is it? Google “doodle” and you’ll find the Google Doodle—what Google calls a “fun, surprising, and sometimes spontaneous” transformation of its logo by a team of dedicated Doodlers to commemorate significant, and not so significant, days: from the seventy-fifth anniversary of the publication of Anne Frank’s diary to “Chilaquiles day.” You will also find a long list of apps that take Doodle as their name, including the ubiquitous scheduling tool. This recasting of the word in the age of the internet takes us far from the freewheeling squiggles, squirls, and whirls decorating the margins of telephone books and notepads—which is, perhaps, what doodling once was, in some near-unimaginable bygone era, when we worked with pens and pencils on paper, and when our attention and our hands wandered in different ways.

“Doodling” describes an activity of spontaneous mark-making by an agent whose attention is at least partially directed on something else. It’s the doodle’s apparent spontaneity and whimsy, but also its complicated relationship to attention—that most anguished-over of modern commodities—that makes it ripe for exploitation by the marketing strategies of app-based companies. That is: the doodle is usefully positioned, around the edges of our work documents and our conscious thought, to help us think about how our minds wander and about what those forms of wandering might yield. In a self-styled “doodle revolution,” which she introduces in a TED Talk and a book, Sunni Brown, founder of a “visual thinking consultancy,” explicitly attempts to capitalize on doodling’s wayward energies. Brown praises the potential of doodling for the workplace, coining a technique that she calls “infodoodling” as a tool for honing the attention of workers and thus increasing their “Power, Performance, and Pleasure” (plus, presumably, productivity—and profit). The goal is to “unlock” the potential of “visual language” to realize the full potential of our brains and “to help [us] think” in different ways. Brown’s self-styled revolution sits within a broader trend toward rehabilitating the act of disinterested drawing, as a kind of salve to our frayed modern attention spans. The doodle-curious consumer will find online a baffling array of derivative self-help- and wellness-flavored “guides” to doodling, full of promises to help us “Discover [our] Inner Whimsy and Find Moments of Mindfulness,” as the Daily Doodle Journal has it, or to “enhance your creativity,” according to another notebook of the same name. Doodling, or: how to cash in on the mind at play.

The activity of distracted drawing was first named “doodling” at a very particular moment: in the 1936 Frank Capra film Mr. Deeds Goes to Town. To be clear, the word “doodle” already existed. It possibly derives from the German dudeltopf, meaning “simpleton,” cementing a strand of aimlessness or surplus value that persists in its current form. Before the twentieth century, it was used to refer to a “simple or foolish fellow.” It is in a courtroom scene toward the end of Mr. Deeds Goes to Town that the word was coined in its current meaning: distracted drawing. The film’s oddball protagonist Longfellow Deeds has been proclaimed insane by his relatives for, amongst other things, playing the tuba and giving away his inheritance money. In his defense, Deeds argues that he plays the tuba to help himself think, and points out that everybody is subject to such inane, or insane, distracted fiddlings (or in the idiom of the film, “everybody’s pixillated,” meaning something like “away with the pixies”). Not least pixillated of all is the court psychotherapist, Emile von Haller, who has been trying to make a case for Deeds as a manic depressive. It is the psychotherapist’s own doodle that Mr. Deeds triumphantly exposes in the film, calling von Haller a “doodler,” which, he explains, “is a word we made up back home to describe someone who makes foolish designs on paper while they’re thinking”:

From Mr. Deeds Goes to Town. Screenshot courtesy of Polly Dickson.