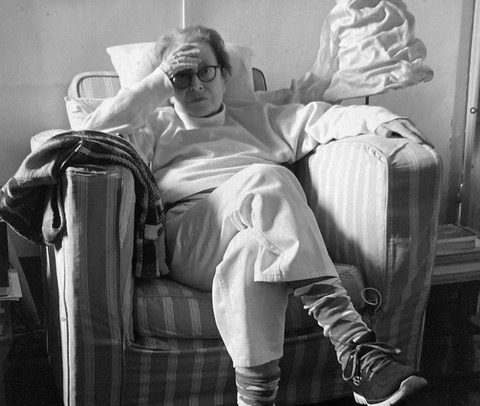

Patrizia Cavalli. Photograph by Mario Martone.

I first met Patrizia Cavalli in 2018, in her apartment near Campo de’ Fiori, where we drank tea with honey and talked from early afternoon until sunset. Every surface was covered with books, papers, notebooks, scissors, and scarves, and each bore the same handwritten note, a warning to visitors: “Do not move! If you move anything, I’ll kill you.” Over the course of two years, we had three more conversations, speaking for five hours at a stretch. The apartment had been her home for decades: in the late sixties, as a twenty-year-old philosophy student, she rented a single room there; she had just left Todi, the town in Umbria where she grew up, and in Rome she felt unmoored and lonely. In 1969, through a mutual friend, she met the writer Elsa Morante, who was then working on her novel History. Morante was the first person to look at Cavalli’s poems, and after reading them, she called to say, “Patrizia, I’m happy to tell you that you are a poet.”

More than fifty years later, Cavalli’s poems are translated and loved across Europe and the United States. Her first collection, My Poems Won’t Change the World (1974), signaled the forthrightness and disregard for authority that would characterize all her work. Cavalli examines the causes and conditions of pleasure and pain, and the moments in life, often imperceptible at the time, that herald change. Her work explores infatuation, boredom, deception, conflict, grief—all in a poetic voice whose nonchalance belies its artistry.

When Cavalli died in June, it felt as though all of Rome wanted to pay tribute. A beautiful ceremony took place at the Campidoglio, where flowers were piled upon flowers. Her admirers and friends crowded the stairwell, and the room where her body lay in state. Cavalli might have criticized the extravagant floral arrangements, but she would have been moved by the words her loved ones chose to speak—some of them her own.